Ep. 49 - Awakening from the Meaning Crisis - Corbin and Jung

(Sectioning and transcripts made by MeaningCrisis.co)

A Kind Donation

Transcript

Welcome back to Awakening from the Meaning Crisis.

So last time we followed Heidegger into the depths where we encountered Eckhart and this non teleological relationship to the play of being, and that led us very directly into Corbin. And Corbin's core argument that gnosis as the way we've been using it relates centrally—the ability to engage in this serious play relates centrally to the imagination. But Corbin is making use of this term in a new way.

He makes a distinction between the imaginary, which is how we typically use the word, the imagination—mental images in my head that are only subjective and have no objective reality, and the imaginal. The imaginal which mediates between the abstract intelligible world and the concrete, sensible world and transjectively mediates between the subjective and the objective. And that is not done statically. All of this mediation and mutual affordance is done in an ongoing transformative transframing, and that the symbol captures all of this.

And then I wanted to bring out Corbin's core symbol. And it's a core symbol that relates directly to gnosis because in gnosis, in this transformative participatory knowing, and this goes to the core of Heidegger's notion of dasein, the being whose being is in question, we have to see self-knowledge and knowledge of the world as inextricably bound up together. In order to do that, we are pursuing Corbin's central symbol, the angel, which, of course, is immediately off-putting to many people, including myself. But I've been trying to get a way of articulating how Corbin is incorporating both Heidegger and Persian Sufism—Neoplatonic Sufism into this understanding of the symbol.

And I recommended that we take a look at the work of, first of all, Stang. The historical work showing how throughout the ancient Mediterranean world and up—through the Hellenistic period and beyond, up until the period of, easily, pseudo Dionysus around, you know, the fifth century, of the common era, there's the pursuit of the divine double. And then the idea is one that is deeply transgressive of our cultural, cognitive grammar, of decadent romanticism. Where we have a—we are born with our true self that nearly needs to express itself ala Rousseau. And the core virtue is authenticity, which is being true to the true self you have, you possess. Rather than, for example, a Socratic model in which the true self is something towards which you are constantly aspiring.

And then I recommended trying to make this—so, and what's the transgressive mythology? Sorry, the transgressive mythology is that the self that I have now is not my true self. My true self is my divine double. This is something that is superlative to me. It is bound to me. It is my double. It is bound to me, but it is superlative to me. It is both me and not me. It's me, as I'm meant to be, as I should be. And that the project, the existential project is not one of expressing a self that you have, but of transcending to become a self that is ecstatically ahead of you in an important way.

And then I pointed out that for many of you, this would still be sort of like, okay, but—I get the transgression, but I still find this notion of a divine double unpalatable. Maybe for some of you, you don't, but nevertheless, I think there is an important way by picking up on, like, by asking the question, why did so many people for so long believe in this so deeply? Picking up on the question of what's going on there and focusing on this aspirational process.

And this takes us back into work that was core to the discussion I made about gnosticism. And this had a resounding impact at various places throughout the series, which is LA Paul's work on transformative experience. And then somebody who's from the same school influenced by Paul, having a different view. Whereas Paul is more—her transformations are more like insight. Agnes Callard's notion of aspiration is much more developmental, but I argued that they can be, I think, readily reconciled together if you see development as a linked sequence of insights that bring about qualitative change in your competence.

So we were zeroing in on this. I'm using LA Paul and Agnes Callard to triangulate into this relationship of aspiration. And picking up, first of all, on Callard's important point that is not addressed—and this is an important point by LA Paul—the deep connections between aspiration and rationality. That rationality is itself an aspirational process. And if we make the process by which we become rational itself, not a rational or irrational process, we will get into a position that is seriously self-undermining.

Similarly, if the way in which you become wise does not involve sort of wise acts and behavior. If the process itself is not itself wise, you're going to get into all kinds of difficulties. If it's not in some sense, a rational process. Again, last time I reminded you how broadly, but I think also deeply I'm using the term rational. Or being educated. I mean, we make ourselves better, maybe even more rational or wiser by going through an education, but education, at least a liberal education is a deeply aspirational process. If that itself is not part of what makes us rational, if it's not itself a rational process, then, of course, our rationality is again being undermined in self-contradictory fashion.

So the basics of this argument is if we take, if we do not understand a kind of rationality Callard calls proleptic rationality, that's the rationality of aspiration (writes Proleptic). The rationality that emerges in education, that emerges in the cultivation of rationality, that emerges in the cultivation of wisdom, then a lot of human behavior is not going to be called rational. And it's going—and that is going to render our notion of rationality, as I've said, self-contradictory and self-undermining in some very fundamental ways. And so again, we see the rejoining of love and reason that was originally talked about so deeply in Plato.

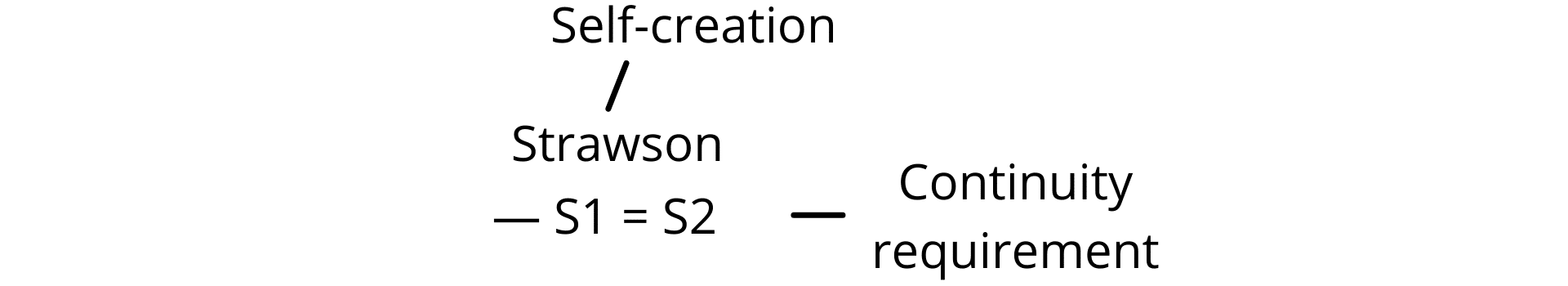

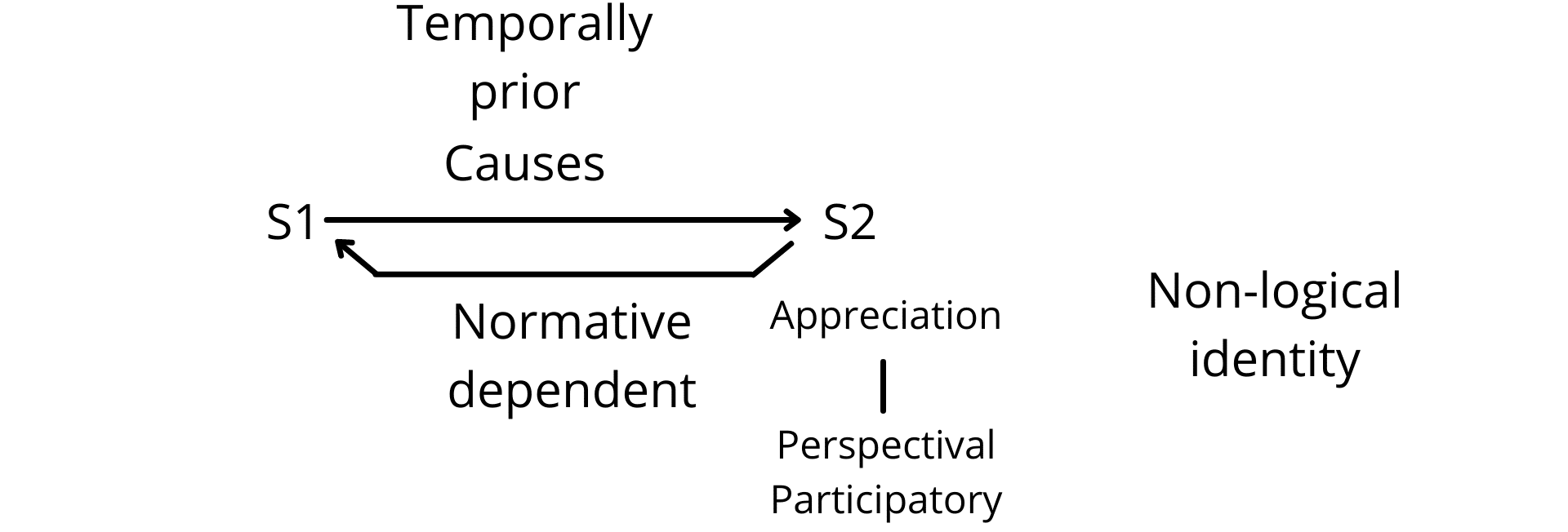

So now we've come back to this problem (erases the board). I gave you the example of somebody in a liberal education. And this is Callard's example, right? Here's the self at this time (Fig. 1a) (writes S1) and the self at this time (draws a horizontal arrow and writes S2) and something, I brought out that Callard doesn't but it's important. Because it's a concise way of talking about the relationship between them and that there isn't a direct inferential relationship between these which is non-logical identity (writes Non-logical identity).

Fig. 1a

Right? This is part and parcel. Like, think about what I said earlier. how can we broaden the notion of rationality outside of logic? If Callard is right then we have to include rationality, proleptic rationality in our model of rationality and involves its non-logical identity. Then, of course, we're stepping beyond sort of a purely logical understanding of rationality yet again for yet another reason.

Okay. So what's the problem here? The other problem is the problem of non-logical identity. So I don't appreciate—always remember both meanings of that term, to deeply—and they're interwoven, the two sides of aspiration. I deeply understand it, and I'm deeply grateful for it. I value it. I don't appreciate classical music. I don't have the taste for it, and I don't get it. And I want to be somebody who appreciates classical music.

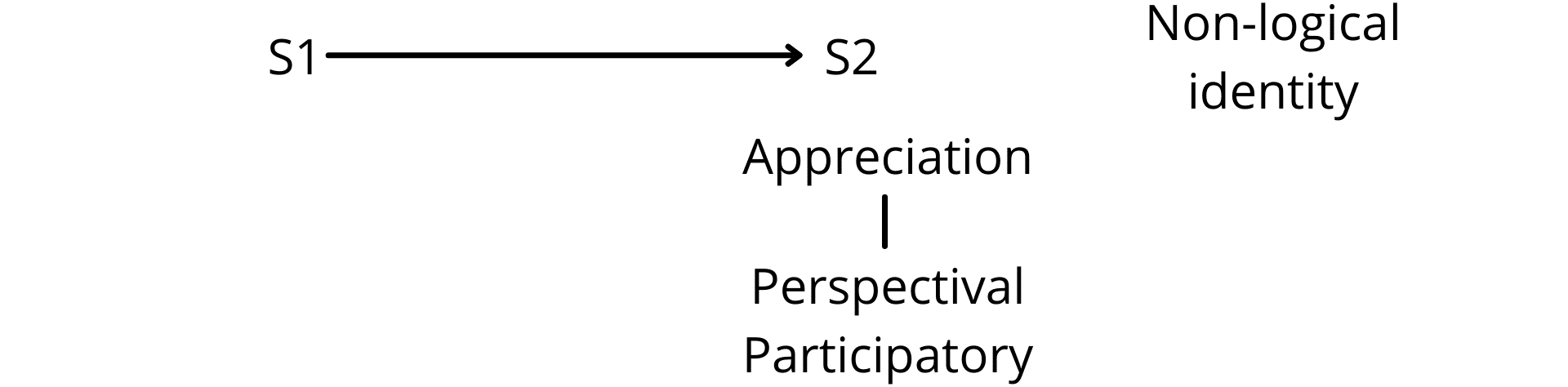

Now, if I want to, if I do that because I want to satisfy a current desire I have, a current value I have. Like, I value impressing my friends or I value attracting members of the opposite sex or something like that. Then, of course, I'm not actually aspiring because this person doesn't appreciate classical music because it impresses their friends or because it helps them in their dating life or for whatever other reason. They appreciate it for a perspectival and participatory knowing that S1 doesn't have. That's the point. The appreciation (Fig. 1b) (writes Appreciation below S2) that S2 has is bound to perspectival and participatory knowing (writes Perspectival and Participatory below Appreciation) of which S1 is ignorant. And that, of course, is one of the central points who you remember of LA Paul's argument about transformative experience. So that looks like there is something, there's a fundamental discontinuity here.

Fig. 1b

Okay. Now they bring up the problem that we need to sort of resolve and bring back and tie this back to the notion of the divine double. I want to talk about a way in which Callard shows us how this (indicates S1 and S2) is problematic as we try to talk about it.

The Paradox Of Self-Creation

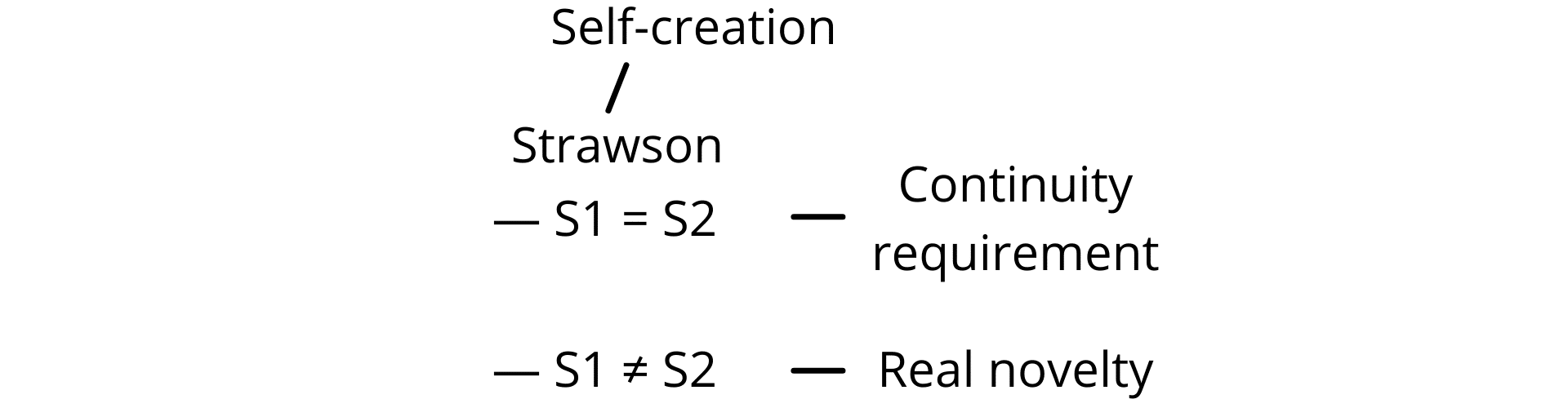

And she makes use of the work of Strawson (Fig. 2a) (writes Strawson). Galen Strawson and he talks about a paradox of self-creation. Now Strawson points out that for self-creation (writes Self-creation)—and doesn't this (indicates S1 and S2) look like self-creation? Here is a self creating itself. For self-creation be truly an instance of self and creation, sort of emphasizing both sides of that, double form, two things are needed.

Fig. 2a

One requirement is a continuity requirement. There has to be something deeply continuous between S1 and S2 (Fig. 2b) (writes S1 and S2 below Strawson), because if they are not the same self, then it's not an act of self-creation. They're not the same self. It's not an act of self creation. So that's the continuity requirement (writes Continuity requirement beside S2). And so I'm going to represent it like this (Writes = between S1 and S2) S1 equals S2. So, what this means is if, like, if S1 is hit by a motorcycle and their brain is damaged and they act and behave in a different way, that's not an act of self-creation. That is not an act of self-creation. S1 has to be totally responsible for S2. Or else it's not an act of self-creation, putting an emphasis on the 'self.'

Fig. 2b

Okay. Now let's shift to the creation side, right? Which is that there has to be real novelty between them (Fig. 2c) (writes S1 and S2 - Real novelty) or else there is no creation involved. If S1 just develops a skill or ability they already have, that is not real novelty. That is just more of the same. That's quantitative development, not qualitative development. So if all that happens is S1, you know, improve the skill, you know, deepens their capacity to acquire something that they already value et cetera, that is not real novelty (writes ≠ between S1 and S2). So real novelty means there has to be a fundamental difference between S1 and S2.

Fig. 2c

Now what Strawson does with this, is he points out, notice how S1 and S2 for the continuity requirement have to be equal, but the real novelty means there has to be a real deep difference between S1 and S2 or it's not creation. And so what he argues is he argues that self-creation is paradoxical. In fact, the point he's trying to make is it's self-contradictory. There can be no such thing as self-creation, alright?

So another way of thinking about this is if you remember, when we talked about this in connection with transformative experience, we can invoke [inaudible] (message us if you know) notion of the idea that you can't sort of create a stronger logic by logically manipulating a weaker logic. No matter how much I manipulate the machinery of predicate logic, I won't get modal logic. Because what I have to do is I have to introduce axioms that are outside—for Godelian reasons, ultimately—are outside the system of predicate logic.

So putting it this way, right, in order to get the real novelty between S1 and S2, I have to introduce something that's outside the logic of S1, the logic of its values and beliefs, that will then make it into S1. But if it comes from outside of S1, it is foreign and strange and therefore it is not an act of self-creation. What that shows— [inaudible] (message us if you know) idea about you can't infer a stronger logic from a weaker logic.

And that goes back to a point we've made before. There is no inferential way. There's no way you can sort of infer yourself from S1 to S2. And this, of course, is part of Kierkegaard's whole point about the leap and the leap of faith. The leap of faith is to leap into a process of development that is going to put you through this kind of qualitative change in your identity.

But Strawson makes this very problematic by saying, this makes absolutely no sense (Fig. 2d) (draws a bracket connecting S1=S2 and S1≠S2). And so we're caught between two things. Either we can break this by saying there is ultimately no self. We could go rabidly empiricist. I'm just a blank slate. And all that happens is stuff from the outside changes me. And then I go for the novelty (indicates S1≠S2), but there's no underlying self. Or I can just do the continuity requirement. I can become sort of a Rousseauan romantic. My self is identical throughout. And all I'm doing is expressing what was already within myself. That's all that's happening. You see empiricism and romanticism. Choose one of the two over the other. And then what Strawson says is you have to make such a choice because self-creation is itself self-contradictory

Fig. 2d

Participating In An Emergence Through Aspiration

Callard says this is all a mistake. And I agree with her. She argues that this is both the empiricism and the romanticism, at least the Rousseauan decadent romanticism is not adequate or accurate of our experimentive developmental change. What breaks this (indicates S1≠S2), I argue, helping her, I believe, is that the relationship between S1 and S2 is one of non-logical identity. Something, of course, we practice—the narrative practice hypothesis—by engaging in narrative all the time and making ourselves into temporally extended selves that have a non-logical identity through time and through development.

So I think both the romantic expressionism and the empiricist, you know, writing upon the blank slate, do not capture what's happening between S1 and [S]2. It's not that S1 is just changed randomly into S2 from the outside. Neither is it the case that S1 simply makes S2. The first self does not make it, right? It's not, it's neither pure passivity nor pure activity. This, of course, is why I've continually emphasized the notion of participation. We'll see how Barfield is trying also to step above both, you know, making and active, completely active making and completely passive reception in his notion of participation.

A better way of describing the relationship is S1 does not receive nor make S2, but participates in S2's emergence. S2 emerges out of S1 to the point that S1 disappears into S2. It's an emergence. We participate in an emergence.

So aspiration is Callard's name for that process by which S1 participates in the emergence of S2 out of S1 such that S1 has disappeared into S2. Self one has disappeared into, has become S2.

Reformulating The Problem Between S1 And S2

So Callard now reformulates the problem that remains. Once we acknowledge this (indicates Fig. 1b), there is a problem that remains because it, again, thwarts our usual cognitive cultural grammar. What's the problem that remains?

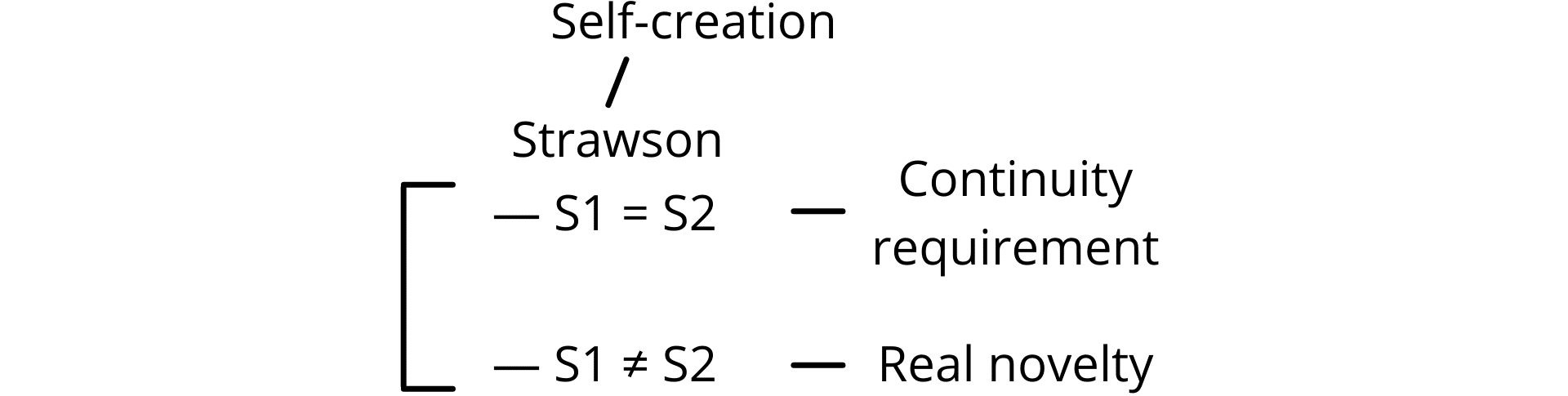

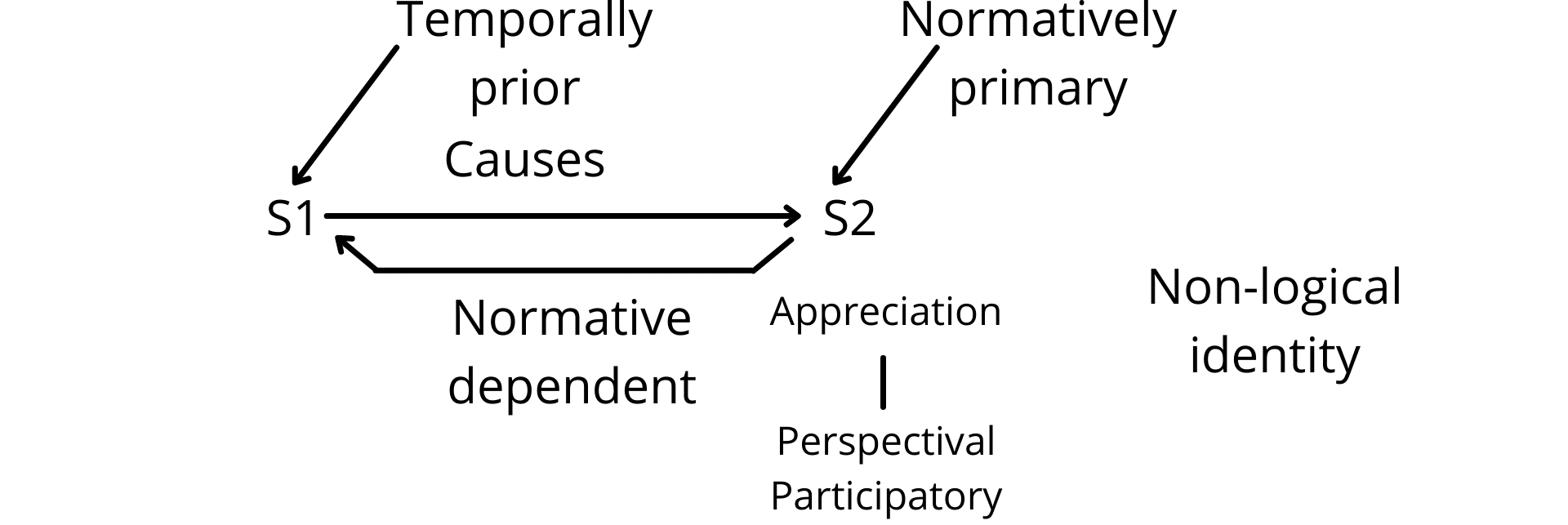

Well, here's the problem. S1, in some important sense, causes S2 (Fig. 1c) (writes Causes between S1 and S2). My actions now are necessary and perhaps, in some important sense, sufficient for setting forth a course of development that is going to result in S2. But although S1 is therefore temporally prior (writes Temporally above Causes) it's before S2 in the arrow of causation (draws an Arrow from S1 to S2), the opposite (draws an arrow from S2 to S1) is the case normatively.

Fig. 1c

S1 normatively depends on S2. All of S1's actions only make sense, can only be justified once S2 comes into existence. Because only S2 appreciates the music. Only S2 is rational. Only S2 understands and justifies the value of rationality, the value of the classical music.

So although S1 causes S2 temporally prior, S1 is normatively dependent (Fig. 1d) (writes Normative dependent under the arrow from S2 and S1) on S2. In terms of normativity, S1 is not primary, it's secondary to S2. The first self—all, everything that the first self is doing ultimately only makes sense when the second self has come into existence. It's only after the aspirational transformation that S1's behavior can be made sense of, can be justified, can be understood.

Fig. 1d

It's interesting because the state that justifies S1's action is the state of S1 having disappeared into and through the emergence of S2. Because only S2 understands and appreciates rationality. Understands and appreciates classical music. Understands and appreciates what it is to be a parent. Understands and appreciates what it is to be a spouse.

So this goes against our normal way of doing things, right? Because we've got—this (indicates S1) is temporally prior, but this (indicates S2) is normatively primary.

So this is—S1 is temporally prior (Fig. 1e) (draws an arrow from Temporally prior to S1), but S2 is normatively primary (writes Normatively primary above S2) in that it's where we find the justification, explanation, legitimation of the aspirational process, that the person that has become in S2. And that's weird for us because normally the thing that is temporally prior and causes is also the thing that is the source of justification and explanation.

Fig. 1e

Now, the temptation here, of course, is to be teleological. To think that in some sense S2 preexists us and causes S1. And I think that's partially what's coming out in the mythos of the divine double. Trying to deal with this really difficult way of thinking. An easy way of thinking about it is, well, the divine double preexists, so already there, fully formed and they're drawing me out teleological until I eventually become S1, right?

But we've already, I've already argued last time, and the time before and earlier on in the series that the teleological explanations are often thwarting us in important ways. And they are certainly thwarting what Heidegger was talking about.

So let's try and do this a little bit more slowly. I want to say S1 has the causal power, but S2 has the normative authority. So S1 has the causal power, but S2 has the normative authority. So how do we relate to the self, to which we aspire?

So when I am S1 and I'm aspiring to be more like Socrates, more rational, how do I now relate to this S2 that doesn't yet exist, but has authority over me? How do I do that? Well, I sort of slipped it in there, right? I sort of slipped it in there when I talked about aspiring to be like Socrates.

The Aspired-To Self

So let's take this step by step. I need... I'm relating to this, the aspired fore self, the self that I aspire to. There's a non-logical identity between my self now and that self then. That self that I'm aspiring to is not logically accessible to me. And those two reasons are deeply—those two points are deeply connected. I can't infer my way to it, right? And my representation of that future self, my current representation to me now has to afford me, somehow tapping into this non-logical identity, this non-logical process, and that representation has to actually afford the transformation of me into the aspired-to self. It has to actually help me become a more rational person.

Now notice, of course, what this means. What kind of thing does this for me? And this is Corbin's point. It's a symbol, not in the imaginary sense, but in the imaginal sense. It's only a symbol that puts these two (indicates S1 and S2) together in the right way. It's a kind of relationship that between things that are non-logically identical, it is not something that is processed in a purely logical fashion. It is a representation that is participatory and it's supposed to help to actually afford you going through the transformative process.

Now let's add a little bit more. My representation of the aspired-to self is it's a symbolic self. It's a symbolic self that I can internalize into my current self anagogically. Remember we talked about this? We become, we transcend ourselves by internalizing how other people's perspectives are being directed on us, right? So remember Spencer internalizes my perspective so that it becomes metacognitive, the stoic aspirant internalizes Socrates, so that he can self-transcend and become more Socratic.

So the symbolic self has to be internalized and notice what's happening in internalization. Internalization is something other than you, yet it becomes something that is completely identified as you, not just as an idea, right? It becomes part of your metacognitive reflective rationality in the case of internalizing Socrates. It becomes part of the very guts of the machinery of yourself.

Why anagogically? Because what I'm doing is I'm internalizing this symbolic self. And what it's doing is it's reordering my psyche so that I see different ways of being in the world. And as I inhabit those new ways of being in the world, they allow me to then re-internalize. Remember this? I internalize Socrates and then I indwell the world in a more Socratic fashion, which allows me to better internalize Socrates so that I indwell the world in a more Socratic fashion. Or perhaps for the Christian. Christ comes to live within them until they live more Christ-like, so that Christ comes to live within them more.

So there's more internalization, more indwelling. And that anagogic process takes off of its own accord, but it's not something that's just passively happening to you. That coupled loop. It's not something you're just making happen. It's something that transcends receiving and making. It is participating.

So what we're doing is that you have this symbolic self that internalizes other people's perspectives, others who live a way they make viable to you. The self you aspire to. But as you internalize them, and that self is transformed, the world is anagogically transformed also. The world is playing an important role in this.

So what I'm suggesting to you is the divine double is a mythos way of trying to capture this dynamic process, which we've discussed at length in this series. And what it does is it represents this process in kind of a linear narrative, and therefore it simplifies it into a simple kind of teleology.

But there's a sense in which I think that teleology is overly simplistic. It's not capturing the participatory nature. The danger with the teleology, of course, is it tends to overemphasize the passive receptivity on the part of S1 in the face of S2.

The Divine Double

So the divine double. I think what people were trying to say with the mythos of the divine double. It's an imaginal symbol that affords the dynamic coupling of anagoge that allows you to participate in the act of self creation. The act, or a better way of putting it, the act of aspiration.

The divine double is you, but it's not you. It's the advanced others that you've internalized into you, but eventually become you. And so you live differently in that in a new world. A way of being becomes viable to you. It is the self you will be. Not the self you are now. But if there is no inkling in your current self of, if there's no inkling of an identity possible, and already beginning to be actualized between your current self and future self, then, of course, it's not going to be part of that aspirational process.

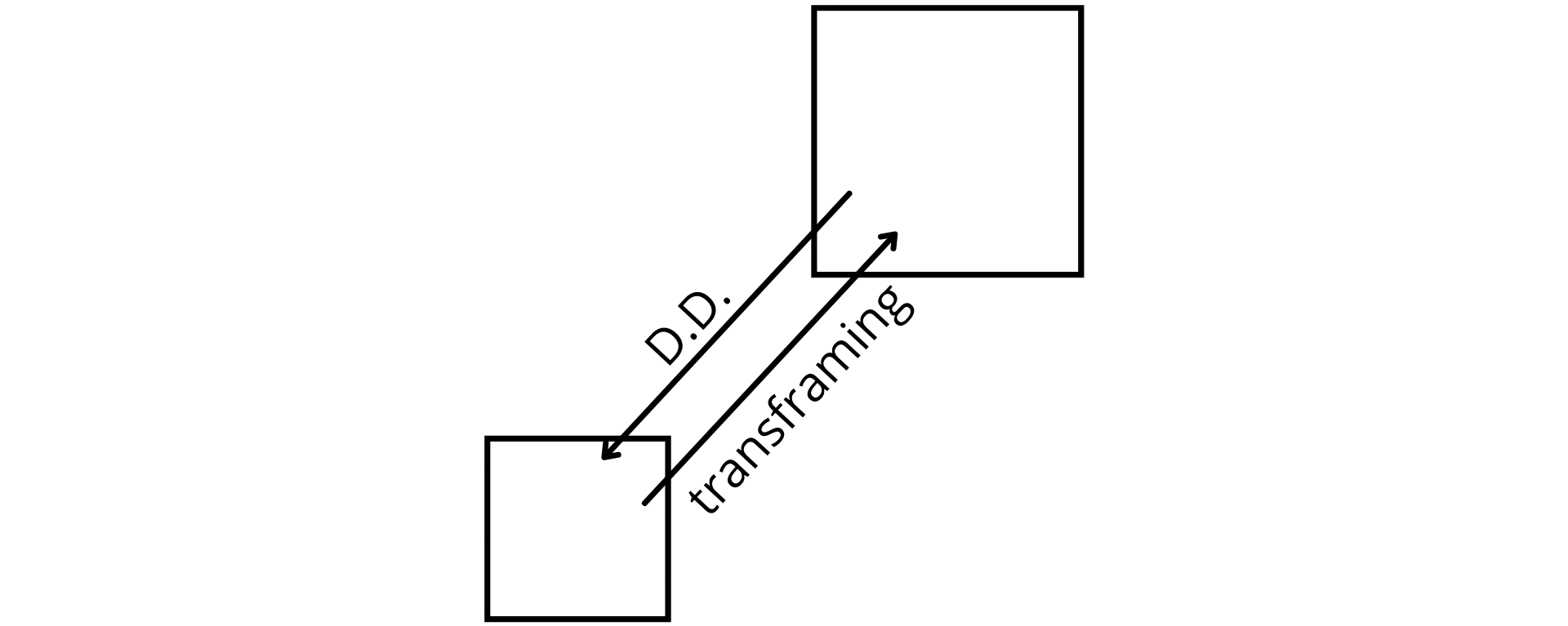

Here's you (Fig. 3a) (draws a square). You're in this frame and you're trying to move to this one (draws a larger square above the first). I'm going to separate them just so I have room to write. Normally this one (indicates the larger square) is round and encompassing. So please allow me this just so I have room to write, right? The divine double allows you to internalize from this more encompassing frame into your current frame (draws an arrow from the large square to the smaller square and writes DD) but that is simultaneously—and here's the shining in (indicates the arrow). Here's the shining in through the divine double. Angels are glorious. They shine. Here's the shining through into your frame. But that shining that internalization affords you moving towards indwelling that more expanded world (draws an arrow from the smaller square to the larger). It engenders a transframing (writes Transframing) so that you can come to indwell, this more expanded frame.

Fig. 3a

The agent and the arena are simultaneously transformed. Here's (indicates the larger square)—so the divine double shines the greater frame into the current frame, but it also draws you out by the way it withdraws into the more encompassing frame. It gives you a sense of the closing into your relevance, but the opening into the greater self.

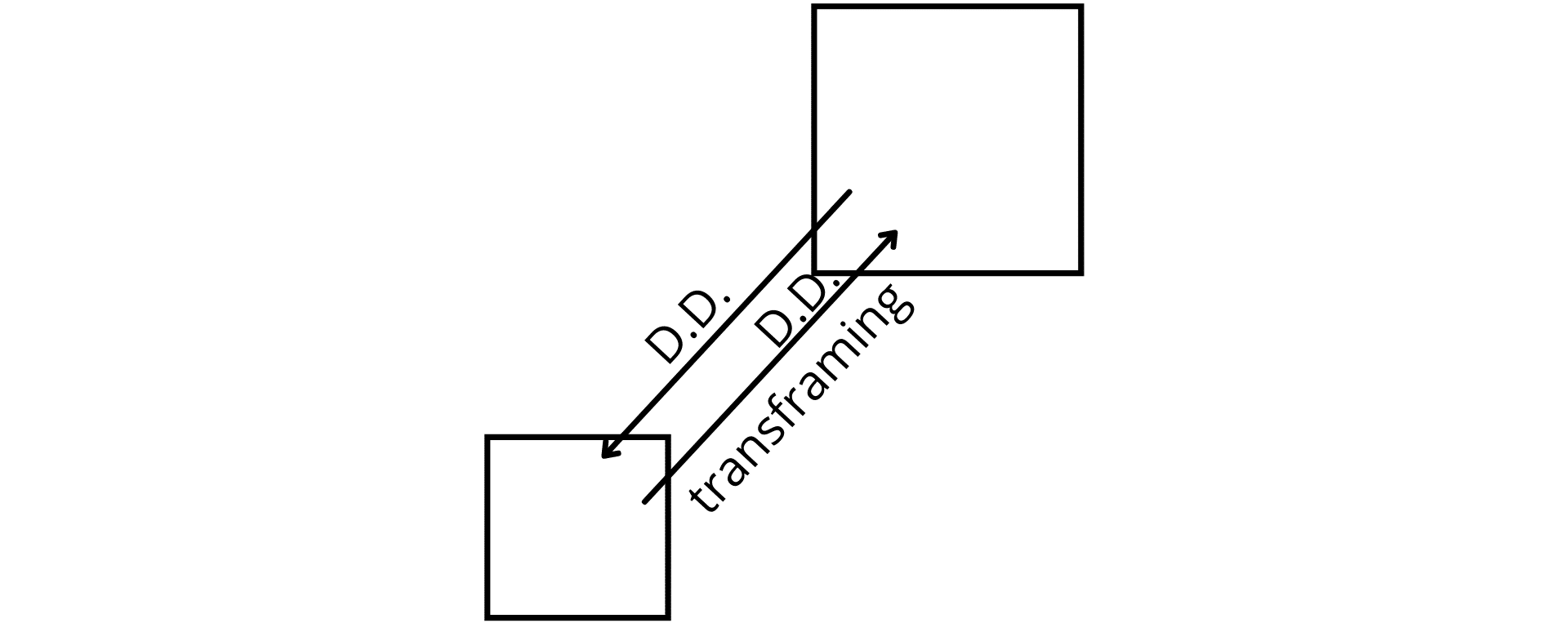

See the gnosis? The divine double allows you to conform—conform in process to the very play of being itself. The way being is shining but also withdrawing. And how that affords your radical self-transcendence, which is always a process also of becoming a greater or better self (Fig. 3b) (writes DD along the arrow from the smaller square to the larger). So what I'm suggesting to you, right, is that the divine double is a central example of the imaginal and that that is often represented in the mythos of angels.

Fig. 3b

So we see how the divine double is transjective, how it's transframing, how it's integrating the abstract form or a concept of the better self. I have some abstract sense of the better self. But it's integrating that with the concrete actions, of causal actions of my current self. They're being—the abstract and the concrete are being drawn together.

Is the divine double subjective? No, that's not right. Is it part of just the objective part of my world? No, that's not right either. It's deeply symbolic in nature and in action. And although it is a symbol, it is not just imaginary. It is imaginal in nature.

It makes, it affords the true development. It affords the core of the being mode. The being mode is not about having things. It is about becoming someone. There's a deep interconnection between the imaginal, the divine double, gnosis, and the being mode.

So the angel in Corbin is a representation of the divine double. And now, the thing to note is that for Corbin, everything has an angel, right? Because it's not only the agent that is being transformed. It is also the arena. Your world is also being opened up. And aspects of being are disclosing themselves that otherwise would not disclose themselves.

Every object is shining and it's also withdrawing into its mystery. Everything is a thing beyond itself. And so you are a thing beyond yourself as an agent, coupled to sets of things beyond themselves as an arena. And you are both going through this coupled process. That's what Corbin means by the angelic aspect of the angelic order of being.

Now, given the way I've tried to interpret and I think explained, but not, I hope dismissively, explained away Corbin—I wouldn't want to make—I want to note, as I said, there's deep connections between gnosis and this divine double, between the being mode, between self-transcendence, between all of this. I'm a little bit unhappy with Stang's term though, the divine double, because it seems to bind us a little too much to the mythos and the teleological simple narrative structure that I think doesn't adequately capture everything that we can see in the work of LA Paul and Callard and the response to Strawson's problem.

And also the notion of divine seems to bind this to theism, which is problematic given its deep connections to gnosis and the Gnostics. And also it precludes non-theistic cultures or sets of religions from having something like this.

Whereas I think you can readily see the divine double in Buddhism where it's talked about the Buddha nature. And the Buddha nature is very much the aspired-self, but things have a Buddha nature. The Buddha nature is both their ultimate real nature, but not their conventional nature. Or you can say the same thing in Vedanta when there is a deep identity perhaps between the Atman and Brahman.

What I'm pointing out is that this way of talking about aspiration can be seen clearly in non-theistic religions. It's clearly in gnosticism, which I think is very much, should not be interpreted theistically. I've tried to show you that. It's clearly the case in Neoplatonism and Stang makes this case for it, both in Plotinus and aspects that at least the Neoplatonic aspects of Dionysus. And that's clearly not theistic.

So I am not going to use the term divine double anymore because I want to try and separate this idea from its commitment to theism. And so I'm going to call this symbolic self, I'm going to call it the sacred second self. The sacred second self. It gives me even more alliteration than the divine double, so I win.

So the idea of the sacred second self. Perhaps this is a way—wow, I don't know. I don't know how, what I'm going to do right now, but I'm going to do it because I have an inkling of its value. Perhaps the notion of the sacred second self is a way of bringing back the idea of having a soul. In fact, that's even the wrong way of putting it. Perhaps that's part of what I'm trying to transgress against. Your sacred second self is the soul that you are becoming. The soul that you are aspiring through and to, and perhaps that is a way of bringing it back.

Carl Gustav Jung

The reason I raise this is because that will allow us to make a bridge to another one of the prophets. Carl Gustav Jung. Because this notion of a relationship to a sacred second self, that is perhaps what we were always talking about when we invoked the word soul, is central to Jung's work.

One of Jung's crucial text for representing the meaning crisis and linking it to his particular particular psychology is the book, Modern Man In Search Of A Soul. So the response to the meaning crisis is that modern man has lost his soul. Now that doesn't mean that a ghost has slipped free of a person's corpus and is somehow floating around untethered. Jung is trying to talk about the—I'm going to argue—the loss of a real relationship to the sacred second self that is needed for responding to the meaning crisis.

And there are deep connections, therefore between Jung and Corbin. And this is not just similarity of argumentation. Jung and Corbin had deep, had a deep interaction, a deep influence on each other. They met regularly together at the Eranos conferences and discussed. As I mentioned, I find that Corbin is more responsible to that relationship than Jung. Corbin talks more often about it explicitly. Whereas I do not see Jung giving enough credit to the influence of Corbin on his thinking.

Nevertheless we can move between Corbin and Jung by picking up on this idea of your relationship to your sacred second self. And I think this is the best way to understanding the process that is central to Jung's whole notion of—it's both a notion of development and a notion of self-transformation and a notion of how to fundamentally respond to the meaning crisis. This is Jung's notion, of course, of individuation.

So how do we get to this notion? Well, we're going to get to this notion—notice each thinker gets into it in a different way. And what Jung is doing, he's picking up on something that is not, it's not really present in Heidegger. It's present in Corbin, but it's present more implicitly than explicitly. And this is psychology, right? That the processes within the psyche that are conducive to responding to the meaning crisis. And by individuation, Jung, and he clearly uses this adjective to describe this as a psychological process.

Now the way to get a little bit clearer about how Jung is using the notion of psychological is right to contrast him to the most important influence on him, his progenitor Freud. And I'm not going to get into a deep analysis of Freud. That would be too far afield.

Freud is a Titan. Even if 95% of what Freud has said is wrong, it doesn't matter. He gets to be in the hall of the immortals because he came up with the idea of the unconscious. He comes up with the idea of it's neither nature or nurture, but the interaction between them in stages of development. These are all just, they become so deeply interwoven with our fundamental way of trying to understand and theorize about ourselves. Like I said. So Freud is a Titanic figure.

However let's pick up on the difference. In what fundamental way did Jung's model of the psyche differed from Freud's? So here, I'm picking up on work done by Paul Ricoeur in his book on Freud and some work done by Storr. Anthony Storr in his work on Jung in an important contrast.

So Freud ultimately has what has been called a hydraulic model of the psyche. So the psyche is basically a Newtonian machine, like a steam engine. Things are under pressure and the pressure has to be relieved and it drives and sort of pushes various processes into operation. So Freud and, of course, this makes perfect sense. Freud has a Newtonian machine, hydraulic model of the psyche. Jung ultimately rejects that, and this is more in Storr than in Ricoeur because Ricoeur's primarily concentrating on Freud. But what Storr argues is that—and this becomes clear in the language and the metaphors that Jung used.

Jung replaces that hydraulic metaphor with an organic metaphor. He sees the psyche as a self-organizing, dynamical system, ultimately as an autopoietic being. So he's sees the psyche as going through a sort of a complex process of self-organization. And that you have to understand individuation as this kind of organic self-organizing—organic self-organizing process that you neither make nor receive, but you participate in.

Archetypes

So this takes us to one of the quintessential notions from Jung. Jung gives a psychological analog of Plato's idea of the form, a structural functional organization. This is the archetypes, the archetypos. People should go back. 'Arche' foundational, like in archeology, getting to the origins and the foundation. 'Typos' the patterns. So the archetypes are the formative founding patterns of the psyche. These are the structural functional organizations by which the psyche self-organizes. The archetypes are therefore very much psychological versions of the Platonic form. And Jung is much better at acknowledging Plato's influence than Freud is, for example.

So the archetypes are not images. The archetypes are not images. You have to take the images and treat them in an imaginal fashion, not as imaginary things you possess in your mind, but as imaginal things that are leading you into the aspirational process of individuation. Think of the archetypes more, the way we talked about earlier. They are systems of constraints. They are virtual engines that regulate the self-organization of what is salient to us.

So if the hero archetype is active in me, it's not—it doesn't mean that I'm carrying around in my head images of the hero. It means that this is an imaginal relationship in which my salience landscaping is being transformed. So I'm anagogically interacting with the world and undergoing aspirational self-transformation so that I am becoming more and more heroic.

Think of the archetypes much more adverbally. than adjectivally. And archetype is a way in which you are anagogically coming to be. Not something in you that you possess and reflect upon.

So Jung argues that all of these, like the psyche as a whole, these archetypes insofar as they are virtual engines of self-organizing processes are autopoietic. They have a life to them, a life to them. These archetypes are the way. Hear this word deeply. Way as method and path of development. The archetypes are the way that psyche makes itself as a living organism. That's what I mean, think of archetypes in a deeply adverbial fashion rather than archetypal—sorry, adjectival. [-]

The Sacred Second Self

So where's the sacred second self? Well, let's talk about the ego (Fig. 4a) (writes Ego and draws a vertical line below) and what Jung called the Self (writes Self below Ego). And he's influenced right by Vedanta. This is the egoic self (indicates Ego), and this is Atman (indicates Self). And the notion of itself with the—see, that was such a bad choice in some ways, because unless you've done all this stuff we've just done and talked about the relation between S self one and self two and you don't—unless you've got the aspirational sense of what self is—if you come to Jung with just decadent romanticism, you're going to hear, oh, but this (indicates Self) is my inner true self that I have to be true to.

Fig. 4a

You're going to relate to the self adjectivally from the having mode. Very great temptation to get into narcissism. I understand why Jung did this (indicates Self) because he capitalizes the S because he's trying to point towards, I would argue the sacred second self, right?

So the ego is the archetype of the conscious mind. The ego is the virtual engine that regulates (Fig. 4b) (draws a circular arrow from the Ego to the Ego) the self organization of the conscious mind. What's the self? Well, it's kind of the archetype of the archetypes. It's like Plato's notion of the good, which is the form for how to be a form. The eidos of the eidos. It is the virtual engine (draws a circular arrow from the Self to the Self) regulating the self organization of the psyche as a whole. It is the principle—the self is the principle of autopoiesis itself. It's the ultimate virtual engine that constellates all the other virtual engines so that the psyche can continue its process of autopoietic self-organization.

Fig. 4b

Remember when a system is self-organizing its function and its development are completely merged. It develops by functions and it functions by developing. So this (indicates Fig. 4b) functional model is simultaneously a developmental model. That's what makes it aspirational. It is simultaneously functional and developmental, right?

So one of the things you can do is you can set up an interaction with these imaginal symbolic entities, the archetypes, and that interaction can be internalized into the perspective—so I can interact with the hero archetype or the shadow archetype, and that will actually be internalized into the way the ego self-organizes.

Ultimately that can become part of this (indicates the vertical arrow), the dialogue between the ego and the self. What Jung calls, the axis mundi, the axis of the world, very maybe overwrought way of putting it. But in some ways I understand what he's trying to get at. This is the process, as I dialogue through the archetypes with the self, the ego's perspectival knowing, and it's participatory being is being fundamentally altered. This is the individuation of the ego. The ego individuates through its dialogue—notice that anagogic resonant way of talking—it's dialogue with the sacred second self. And notice ultimately how that falls back to Plato and Socrates. This notion of dialogue.

This, of course, is the basis of Jung—and notice the similarity here, again—of Jung's deep criticism of literalism and fundamentalism. Because, of course, the imaginal (Fig. 4c) (draws a horizontal line across the vertical), the archetype as imaginal sits right here. It mediates between these.

Fig. 4c

Why is Jung so critical of literalism and fundamentalism? Because it is to reduce the imaginal nature of the archetypes into simply being imaginary. It is to lose the being mode and it is the simply having of subjective representations, rather than engaging in the process of individuation. It's a form of inflation in which the ego pretends that it is sufficient unto itself and tries to take on the complete role of the self, tries to just have an identity rather than continually becoming in the process of individuation. It is deeply disturbing to see someone who is, would claim to be committed to a Jungian approach being deeply enmeshed or involved with proponents of literalism or fundamentalism. This would be, I believe, a deep form of self-contradiction.

Criticism Of Jung

What's my main criticism of Jung? Which will then allow me a counter criticism to Corbin. And this is a criticism that Corbin makes of Jung, but it's also independently a criticism that Buber the existentialist, the person who talked about the I-It and I-Thou and picked up on the difference between the being mode and the having mode as well. There's also convergence with the criticism that Buber made of Jung. (Text overlay appears "For a good discussion of the Buber/Jung debate" beside book, The Search For Roots)

Jung understands all of this (indicates Fig. 4c), and that's how I've explained it to you as intra-psychically happening within the psyche. Now my friend and colleague, Anderson Todd tells me that towards the end, Jung seems to be breaking out of this purely psychological way of talking. But for most of his writing, Jung understands all of this—and this is, of course, this is problematic. And this is what Corbin was trying to get him to see. He was understanding all of this as subjectively. His Kantianism was making him see this as all happening in a very deep sense within the mind. That the archetypes are understood ultimately for a very long time in Jung as subjectively, rather than transjectively. And because of this—and then this is where Buber's criticism bites into Jung—Jung misses all of the existential modes that Buber wants to talk about. Jung can't talk about the, you know, the having and the being modes, because he doesn't have a way of representing the transjective relationship.

For Corbin, Jung seems to be reducing the imaginal to the imaginary. And for Corbin, this is a mistake because the mystical, for Corbin, doesn't just disclose the depths of the psyche. The mystical also discloses the depths of the world in an integrated, coordinated fashion. That's because Corbin is ultimate Neoplatonic and not Kantian. This is why I said, if you don't understand Kant, you don't get Jung.

Now, in fairness to Jung, Jung can say, but what's missing from Corbin is the psychology. What's missing from Heidegger is a psychology. How does all of this existential, ontological, Neoplatonic stuff play out within the psyche? If you're going to talk to me about internalizing, I get it. I'm answering on behalf of Jung. Jung can say, I get it. I leave off the indwelling in the world that Corbin is pointing to, and Heidegger has been pointing to. But what Jung can say is, yeah, but you haven't told me what the internalization looks like. How does the imaginal get internalized into the depths of my psyche?

So what I'm suggesting to you—this is neither Corbin nor Buber, nor is it Jung, but Vervaeke is arguing to you that you can integrate the three of them together. And then you get something much better than either Jung or Corbin or Buber. I want to take a look next time at somebody who shares a lot with all three of these: Corbin, Jung, and Buber. And like them, is deeply influenced by Heidegger. And that's Paul Tillich.

Thank you very much for your time and attention.

- END -

Episode 49 Notes

To keep this site running, we are an Amazon Associate where we earn from qualifying purchases

Heidegger

Martin Heidegger was a German philosopher who is widely regarded as one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century. He is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism.

Henry Corbin

Henry Corbin was a philosopher, theologian, Iranologist and professor of Islamic Studies at the École pratique des hautes études in Paris, France.

Gnosis

Gnosis is the common Greek noun for knowledge. The term is used in various Hellenistic religions and philosophies. It is best known from Gnosticism, where it signifies a spiritual knowledge or insight into humanity's real nature as divine, leading to the deliverance of the divine spark within humanity from the constraints of earthly existence.

Active imagination

Active imagination is a conscious method of experimentation. It employs creative imagination as an organ for "perceiving outside your own mental boxes."

Dasein

Dasein is a German word that means "being there" or "presence", and is often translated into English with the word "existence".

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolution and the development of modern political, economic, and educational thought

L.A. Paul

Laurie Ann Paul is a professor of philosophy and cognitive science at Yale University. She previously taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Arizona. She is best known for her research on the counterfactual analysis of causation and the concept of “transformative experience.”

Agnes Callard

Agnes Callard is associate professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago. Her primary areas of specialization are ancient philosophy and ethics.

Book Mentioned: Aspiration: The Agency of Becoming – Buy Here

Galen Strawson

Galen John Strawson is a British analytic philosopher and literary critic who works primarily on philosophy of mind, metaphysics (including free will, panpsychism, the mind-body problem, and the self), John Locke, David Hume, Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard was a Danish philosopher, theologian, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher.

Advaita Vedanta

Advaita Vedānta is a school of Hindu philosophy, and is a classic system of spiritual realization in Indian tradition.

Ātman

Ātman is a Sanskrit word that means inner self, spirit, or soul. In Hindu philosophy, especially in the Vedanta school of Hinduism, Ātman is the first principle: the true self of an individual beyond identification with phenomena, the essence of an individual. In order to attain Moksha (liberation), a human being must acquire self-knowledge.

Brahman

Brahman connotes the highest Universal Principle, the Ultimate Reality in the universe. In major schools of Hindu philosophy, it is the material, efficient, formal and final cause of all that exists.

Plotinus

Plotinus was a major Hellenistic philosopher who lived in Roman Egypt. In his philosophy, described in the Enneads, there are three principles: the One, the Intellect, and the Soul.

Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung, was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung's work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philosophy, psychology and religious studies.

Book Mentioned: Modern Man in Search of a Soul - Buy Here

Eranos

Eranos is an intellectual discussion group dedicated to humanistic and religious studies, as well as to the natural sciences which has met annually in Moscia (Lago Maggiore), the Collegio Papio and on the Monte Verità in Ascona, Switzerland since 1933.

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst.

Paul Ricœur

Jean Paul Gustave Ricœur was a French philosopher best known for combining phenomenological description with hermeneutics.

Book Mentioned: Freud and Philosophy - Buy Here

Anthony Storr

Anthony Storr was an English psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and author.

Book Mentioned: Jung - Buy Here

Jungian archetypes

Jungian archetypes are defined as universal, primal symbols and images that derive from the collective unconscious, as proposed by Carl Jung. They are the psychic counterpart of instinct.

Martin Buber

Martin Buber was an Austrian Jewish and Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism centered on the distinction between the I–Thou relationship and the I–It relationship.

Alfred Ribi

Book Mentioned: The Search for Roots - Buy Here

Other helpful resources about this episode:

Notes on Bevry

Additional Notes on Bevry