Ep. 48 - Awakening from the Meaning Crisis - Corbin and the Divine Double

(Sectioning and transcripts made by MeaningCrisis.co)

A Kind Donation

Transcript

Welcome back to Awakening from the Meaning Crisis.

So last time we were pursuing in-depth, trying to understand Heidegger's work as a prophet in the Old Testament sense of the meaning crisis. We took a look at this notion of the thing beyond itself and realness as simultaneously the shining into our framing and the withdrawing beyond our framing in a deeply inter-affording inter-penetrating manner.

We took a look at this deeper notion of truth. Not truth as correctness, but truth as aletheia. That which grounds the agent arena relationship in attunement and allows us the potential to remember being by getting into an attunement with it's simultaneous disclosure and withdrawal. But we can forget that; we can get into a profound kind of modal confusion. And this is the history of metaphysics as the emergence of nihilism, we can forget the being mode. We can get trapped into the having mode in which the metaphysics is a propositional project of trying to just use truth as correctness.

And we misunderstand Being as a particular being, we try to capture the unlimitedness aspect of being. But we only do it at the limit, which Heidegger's deeply critical of. And so we understand being in terms of a supreme being. A being at the limit and beyond the limit, this is onto-theology. We understand God as the supreme being. And this is deeply enmeshed for Heidegger with nihilism because this onto-theology, this theological way—at least a version of theology from, sort of, classical traditional theism—this way of understanding being gets us into the deep forgetfulness and modal confusion that is the hallmark of nihilism.

But, of course, we could perhaps remember the being mode. And this is what Corbin, following Heidegger, talks about as gnosis. We can understand what this gnosis is. What does it look like? What would it be like to remember, from the being mode through aletheia, being? So I want to pick up on this idea of gnosis's serious play in a particular piece of work by Heidegger. Heidegger discusses, and this Avens discusses this in his book. And Caputo also discusses this in his excellent book, The Mystical Element In Heidegger's Thought. So both Avens and Caputo talk about this. Heidegger's commentary on the poetry of Angelus Silesius.

Angelus Silesius was a poet who was basically trying to put into poetry—and we can, sort of, think of, or at least foresee some things Barfield is going to say. He's trying to put into poetry the work of Meister Eckhart, who was one of the great Neo-platonic mystics within the Rhineland mystics that I talked about so long ago. Now what's important of course for Meister Eckhart and this discussion of gnosis as the remembering through aletheia of the being mode that alleviates the forgetfulness, alleviates nihilism, is that Eckhart, of course is also experiencing this as a form of sacredness. As something that is appropriate to a religious context.

So we also noted in conjunction with that, that Tillich is going to be deeply influenced by Heidegger's critique of ontotheology, but he is also going to situate it within—although he's going to radically revise what this means—a traditional religious term, which is idolatry.

The Rose And Physis

Now let's think about Heidegger's commentary on this poem. So what's the poem? Here's the poem, what's in translation. So we, unfortunately, lose some of the poetry.

The Rose is without why.

It blooms because it blooms.

It cares not for itself.

Asks not if it is seen.

So it's interesting that when Heidegger is doing this, he's actually talking about this word physis (writes Physis). The Greek word, which, of course, is the core of the word physics, which again, he's trying to get back to a re-experience of the physical as important way of remembering the being mode. This is again why I think many people misunderstand. And I've argued this elsewhere and I'm going to keep coming back to it. The response to the meaning crisis is somehow a rejection of physicalism and the physical. Heidegger's instead, trying to show you how it can more deeply be remembered.

Now he's picking up on the Greek for this term (indicates Physis). So again, he's doing some etymological work here. Physis means, you know, blossoming forth from itself, springing forth from itself. Very much like the rose is being described. And think about what this means. This is what Heidegger says. The blossoming of the rose is grounded in itself. Has its ground in itself. The blossoming is a pure emerging out of itself. Pure shining.

Now what's going on there? Now, of course, Heidegger will never talk just about the shining, even though he doesn't explicitly mention it here. It's implied and we should therefore remember it in the phrase, 'emerging out of itself,' that the shining is simultaneously withdrawing. We get a sense of the depth of the rose in its physis, because as it shines, it shines in a way that's showing that it's shining out of itself, shining out of its depth, shining out of that into which it withdraws as it presents itself to our phenomenological experience.

So here Heidegger is—he's picking up on one of Eckhart's maxims. This is what Eckhart said, live without why. Or you could also translate it as live without a why. Now that sounds to some people like, what? That sounds like a meaningless existence. There's no why there's no purpose. There's no grand unifying purpose.

Think about it a little bit more carefully, right? Is that quest for the grand culminating purpose? Is, is that maybe, perhaps, coming from the having mode and not from the being mode. Eckhart is not proposing meaninglessness. He's actually proposing a non-teleological way of being. A non-teleological way of being. It's to move beyond.

There's no narrative to the rose. The rose is not that it's sort of lacking. It's beyond, above and beyond the narrative. So a way of thinking about this—and I promised to come back to this earlier in the series and I've come back to it now (draws an east pointing arrow). And we talked about this in a couple places. We talked about it back with the Stoics. And we talked about it when I was talking about, perhaps we can't get back to a narrative in the sense of a teleological aspect to physis, to the physical universe. But maybe the universe as a whole is like the rose. Maybe it's blooming from itself, grounded in itself, blossoming, shining from itself while always, always withdrawing. And think about how well that actually comports with, you know, the physics of an ever-expanding universe coming out of the Big Bang, but grounded in the quantum. Like, is that so foreign a way of talking about the universe, that it's very much like the rose? And we get better at being connected to its physis if we drop the axial age requirement that there be a teleological narrative to it all.

Narrative And Non-Logical Identity

This horizontal narrative. Look, it's important. The horiz—narrative gives us practice in something. It gives us important practice in something. We're going to come back to this because the thing about narrative is narrative gives you deep practice, cognitive existential practice in non-logical identity (Fig. 1a) (writes Narrative non-logical identity). We've talked about this and the relationship it has to the symbol.

Fig. 1a

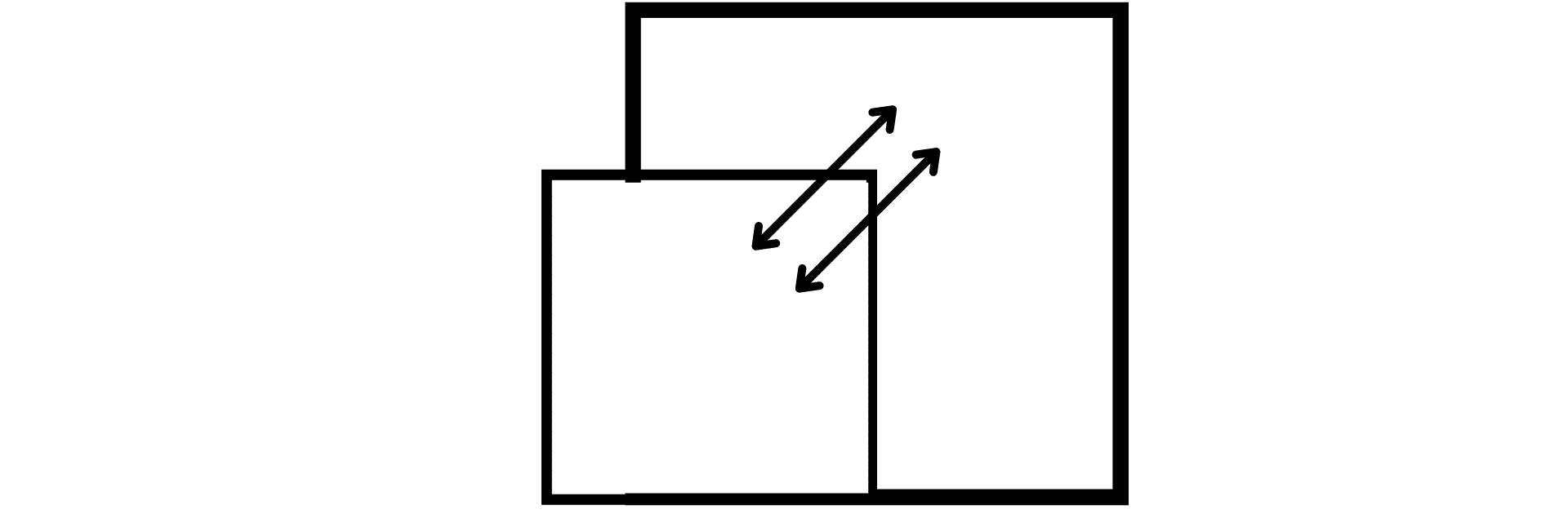

So let's talk about it, first of all, in the symbol. Remember, here's a framing (Fig. 2) (draws a square) and then you transframe (draws a larger square outside the small square) and then there's a non-logical identity between the world inside the frame and the world outside the frame (draws a double headed arrow between the two squares) and a non-logical identity between you here and you there (draws a double-headed arrow between the two squares). Remember this? This non-logical identity between who you are inside this frame and who you are after, right? A transframing. Remember that when we talked about aspiration? When we talked about aspiration, remember that?

Fig. 2

Now the thing about narrative is that narrative is a way of representing through time (indicates the horizontal arrow) symbolically (Fig. 1b) (writes Through below Narrative non-logical identity). We can often rep—oh, no, sometimes we're just talking about, a kind of transformation through time. But one of the things that narrative does, is through time, it represents how you have a non-logical identity to yourself.

Fig. 1b

Look, I was born in Hamilton in 1961. I'm not in Hamilton now. I'm not, you know, nine pounds. I'm 190 pounds. That kid that was born in Hamilton, can't speak English. Couldn't walk, couldn't move around. Certainly couldn't teach this. That kid is in so many ways different non-identical from me, but in another sense, it's me. And I'm him, right?

Narrative is a way of tracing out and training us in being able to work with non-logical identity, to work with this kind of fundamental transformation. But what we can do, what I think Eckhart is pointing to (erases the board except the horizontal arrow), we can exapt that ability for non-logical identity (Fig. 3) (writes Exapt). We can exapt that symbolic identity. And instead of thinking of it as unfolding narratively across time—remember how the Stoics criticized this? Stop pursuing fame and glory and wealth and power. Instead of the horizontal narrative, we can do the vertical ontology (draws a downward arrow across the horizontal arrow). We can do the vertical ontology in which we are connecting the depths of ourselves to the depths of being in a non-teleological being mode. This is, I think, is what. Heidegger is pointing to and what Eckhart is pointing to.

Fig. 3

Pure Shining And Pure Withdrawal

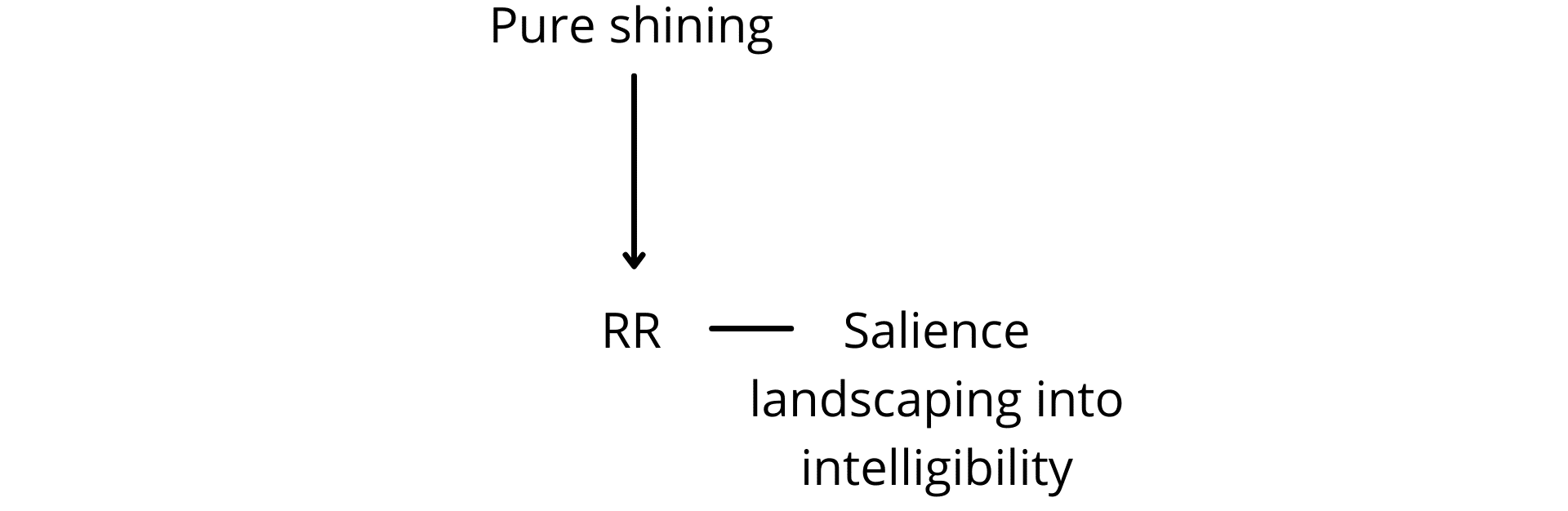

So, as I mentioned, the pure shining. Let's put this on here (erases the board). Here's the pure shining (Fig. 4a) (writes Pure shining), the way the rose shines, phenomenon, experience. Right? I think that's shining. I think we can talk about it as relevance realization (writes RR below Pure shining), the salience landscaping into intelligibility (writes Salience landscaping into intelligibility). Salience landscaping into intelligibility.

Fig. 4a

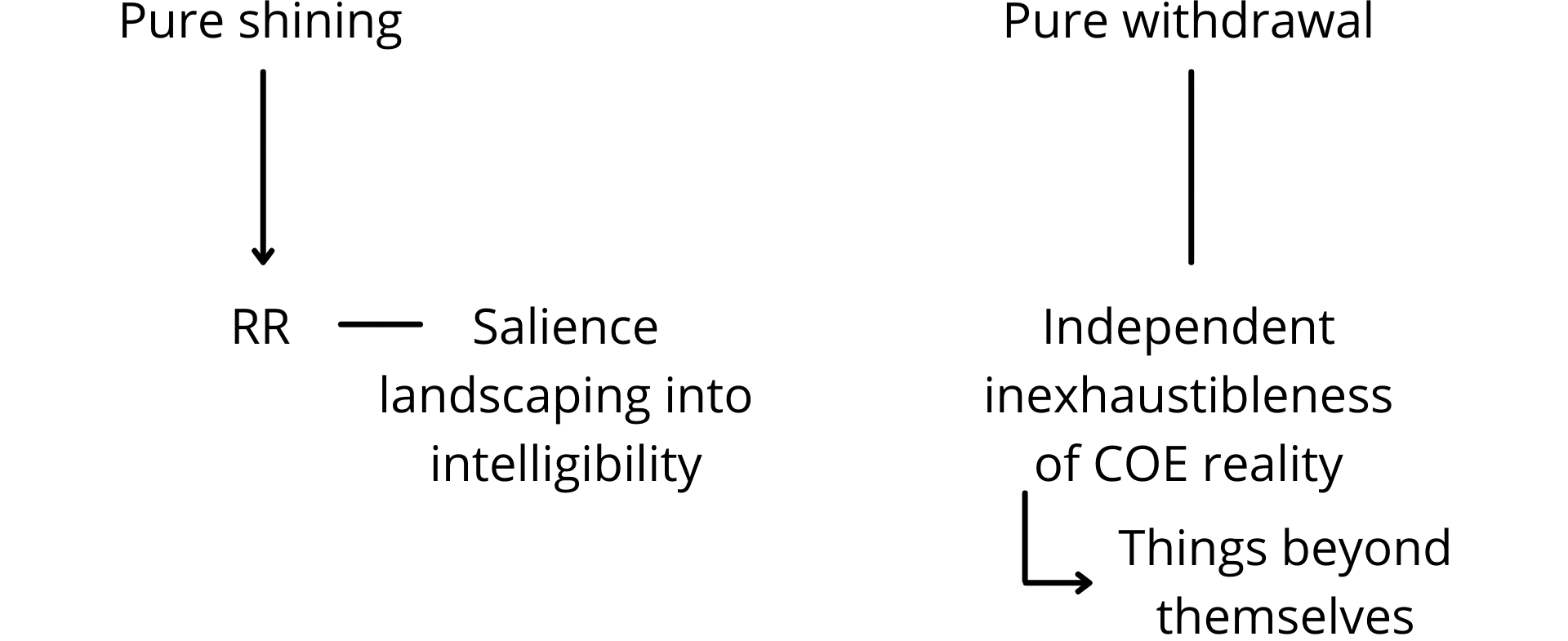

What about the pure withdrawal? (Fig. 4b) (writes Pure withdrawal beside Pure shining) This is the independent inexhaustibleness of a combinatorially explosive reality, right? Independent, because it is inexhaustible (writes Independent inexhaustible). We cannot drink it dry. The Tao Te Ching. Right? And the Dao is a way of understanding physis the way Heidegger's talking about. Look at the book, Heidegger and Asian Thought, or Heidegger's [Hidden] Sources, where it talks about the connection to Daoism and he might've been directly influenced by it. Right. And the Tao Te Ching talks about, you know, how the Dao is a well that is never used up. It is inexhaust—it is the inexhaustible mother. So the independent inexhaustibleness of a combinatorially explosive reality (writes of COE reality below Independent inexhaustibleness). The things—the thing, and the things beyond themselves (writes Things beyond themselves below Independent inexhaustibleness of COE reality).

Fig. 4b

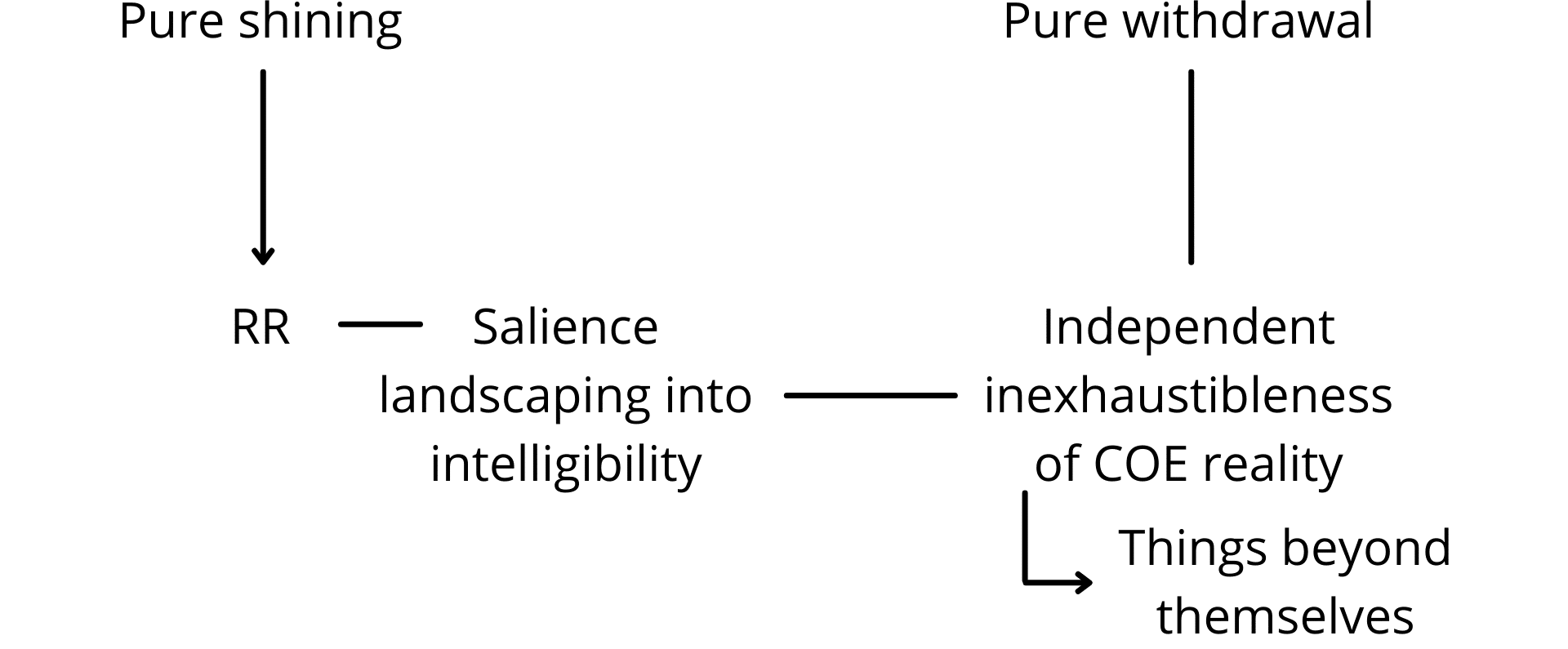

I think we can draw these two together (Fig. 4c) (draws a line between Salience landscaping and Independent inexhaustibleness), as I've already argued, into this. I want to say this very carefully, right? We can see this, we can experience this from within the being mode in the following way. A trajectory, a trajectory of transframing that is always closing upon the relevant, while always opening to the moreness. It's a trajectory of transframing that is always closing upon the relevant as it is simultaneously always opening to the moreness.

Fig. 4c

When we recognize that aletheia, remember it from within the being mode so that we can accentuate it and celebrate it that's what I've argued sacredness is. And that seems to line up very well with what Eckhart is saying.And one of the things I have about Heidegger is he's reticent to talk about this in terms of sacredness. Tillich isn't. Heidegger is. And that's part of why I think he, he goes astray in certain ways.

So we can think of realness as a tonos (writes Tonos). This creative tension. It's something that Barfield brings out tremendously and clearly in his work. We can think of realness as a tonos, as a creative polar tension between, you know—Look at the word confirmation, coherence, and moreness. And remember you need both.

If the virtual reality just has the confirmation and the coherence, it falls flat. If it can't provoke a sense of opening and wonder, if there's no element of surprise. If it's all assimilation and no accommodation. If it's all assimilation and no accommodation—remember accommodation is experienced as all in wonder? If it's all of that, if it's just assimilation—sorry, and not accommodation, if it's just the foreclosure and never also the opening. If it's just the homing and never the numinous. See these themes? Then it's not real. It's not experienced as real.

And that being able to attune—and this is where the Dao was so, like Daoism is such a powerful symbolism, right? You have the yin, which is the confirming. Drawing down. And the yang is the opening up. And both of those interpenetrate. Think of the classic Dao symbol: within the white is the black dot, within the black is the white dot. And they're sinuous because they're interpenetrating, interleaved together.

And all of that is the disclosure of the inexhaustibleness of the Dao. I'm trying to make a convergence argument here. Daoism is all about the serious play. The serious play with the serious play of being. And that's how Corbin describes it. When he's talking about gnosis he talks about the play of being. So does Avens when he's talking about Corbin. So I'd like to pass now explicitly leaving Heidegger behind now and moving into Corbin.

Persian Sufism And Corbin

I've already noted how deeply Corbin was influenced by Heidegger. But he's also, he's deeply influenced by Platonism. And that leads him into probably his deepest influences. So all of these things are important to Corbin: Heidegger, the Neoplatonic tradition, but most especially Neoplatonism within Persian Sufism.

So Sufism (Fig. 5a) (writes Sufism) is the mystical branch of Islam and Corbin is particularly focused on Persian sufism (writes Persian above Sufism). And I think that's something important that we should just pause to note. One of the gifts of Corbin's work is to help us remember—and thereby overcome our ethnocentrism—how central—and I use that term decidedly—how central Persian philosophy is to the history of philosophy in the world.

Fig. 5a

Persia plays a pivotal role. And I don't mean it as a neglected middle—well, it is by us, but it shouldn't be a neglected middle. Persia plays a central role between, for example, between the Arab world, the European world, and the world of India and China, the Asiatic world. And what's really important about Persian Sufism—and I can't, the history of Persia is a fraught one.

We sort of think of now. And this is because of, you know, the history and since the seventies, we think of, you know, Iran is sort of rabidly Muslim and something like that. And that's played up by propaganda. It is not to deny that there is an Islamic fundamentalist totalitarian regime in control in Iran. But what it is—what I'm trying to do is challenge that as a monolithic representation of all of Persia and all of Persian culture. Instead, you have to remember that Persia was made Muslim via an Arab invasion that was nothing less than a genocide. And I know Persians. They remember this deeply to this day. So the attitude towards the Arab overlords is something that has become deeply woven into Persian culture.

Why am I saying that? Because that means that the Persians were especially attracted to, at least for huge periods, Rumi and others, they are deeply attracted to Sufism. They're attracted to a mystical interpretation of Islam precisely because they are trying to find a form of liberation from an oppressive Arab empire. So that means that it's important that it is Persian Sufism, and this deeply has an impact on Corbin. He's really taken up by this and how that Persian Sufism has a much more—I'm trying not to be dismissive here—as a much more flexible relationship to Islam than you might think of when you think of Iran today in the world.

And so, like, reading the poetry of ancient Persia—well, not even ancient Persia—the poetry from Persia since the Arab invasion and genocide, I think is an important thing to do too. We remember these aspects. Now Corbin did all of that. He read this stuff deeply. Profoundly, repeatedly, extensively.

Now there's ways in which he suffers. There is ways in which as, you know, a French men, he will fundamentally misunderstand some of this literature. And I'm not going to say that he is a perfect interpreter, but I will say he is an insightful and important interpreter. So he draws all this in. He's drawing in the Heidegger and the Neoplatonism and espe—and this was something that you have to, and the Persian Sufist know this—the deep influence of Neoplatonism (Fig. 5b) (writes Neoplatonism above Sufism) on Sufism.

Fig. 5b

So there's Neoplatonism then there is a mystical form of Islam, deeply influenced by Neoplatonism and then Corbin is bringing that into understanding Heidegger. And then he's bringing all of that as a way of trying to explain this gnosis and how this gnosis can ultimately be salvic and redemptive in the face of the meaning crisis. Remember, he talked about gnosis as transformative, salvic, participatory knowing? A deep at onement, attunement, at onement. See how all these things are resonating with each other?

Now, what does Corbin bring to this that we don't have in Heidegger? And here's where I think you can see the influence of Sufism and the rich world of Persian poetry upon him. And I think this is an important thing.

Corbin sees there, and argues for—reading Corbin is very different than reading—it's like Heidegger in the sense that it's difficult, but because he's trying again, to break out of the cognitive and cultural grammar, but it's very lyrical. It's very beautiful. But sometimes you pick up the beauty and that's again the influence of the Persian poetry on him. You pick up the beauty without, and then you, you, you should pause and say, yeah, but did I really understand what he just said? So you have to read, you almost have to recite Corbin and repeat Corbin.

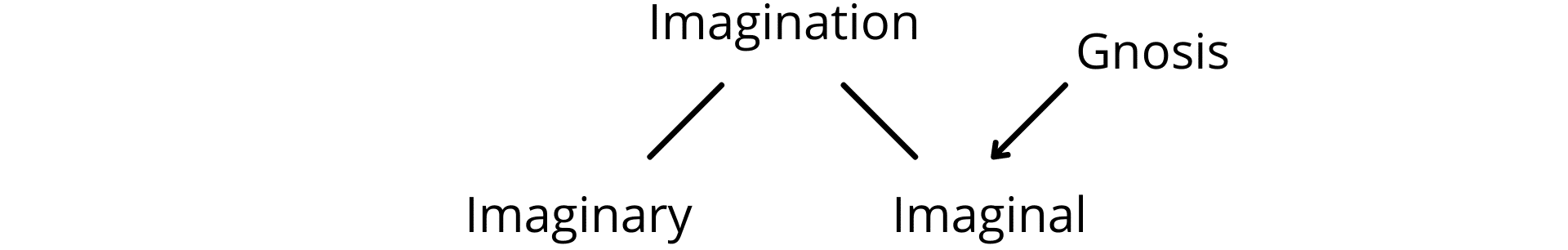

Now he uses that kind of argumentation to make a claim that the recovery of gnosis is bound up with imagination in an important way (writes Imagination). And you may think, "oh no, John is just going to jump off into some decadent form of romanticism." No. Corbin is doing something very interesting about this.

I recommend the Lachman book that I've recommended for Corbin. See also Aven's book, The New Gnosis that I've just mentioned. See all of Cheetham's work, The World Turned Inside Out, Imaginal Love, the third one I think it was the angelic nature of being, I can't remember the third title. Anyways, we'll put all the panels up. Cheetham's work on Corbin—in fact, I recommend reading Avens and reading Cheetham before you read Corbin.

So if you take a look, Corbin is doing something very important with this. He's not using this word (indicates Imagination) in the way we typically use it. And in order to bring that out, he actually makes a distinction. A distinction that's going to be important, especially when we turn to talk about Jung.

Distinction Between Imaginary And Imaginal

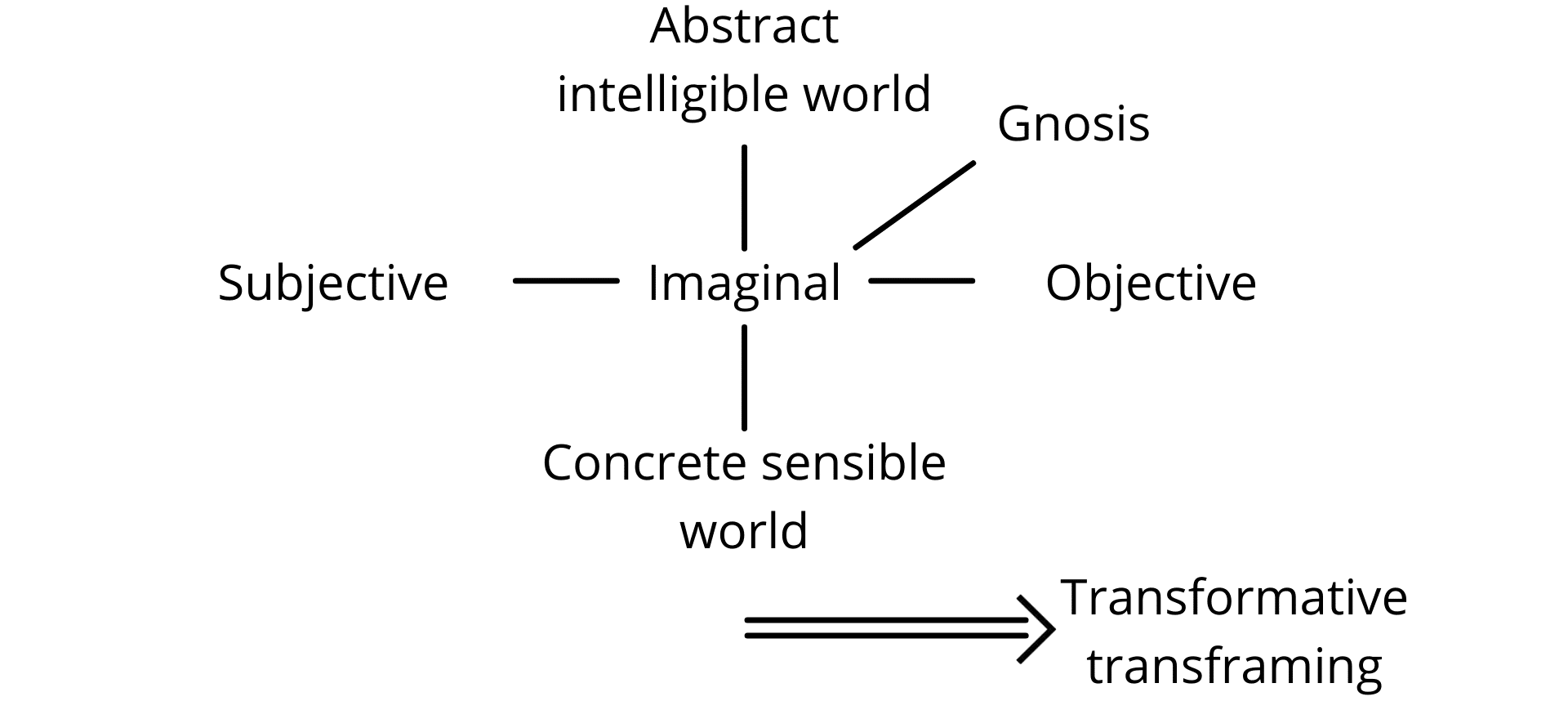

He makes a distinction between the imaginary (Fig. 6) (writes Imaginary below Imagination) and what he calls the imaginal (writes Imaginal). And it's the imaginal that is bound up with gnosis (Writes Gnosis above Imaginal).

Fig. 6

So imaginary. The imaginary is what we typically mean when we invoke the word imagination. We mean the purely subjective experience of generating inner mental imagery, which we know is not real and that it's sort of completely in our control and we can play with it as we wish. That is explicitly, clearly, definitively not what Corbin is talking about.

Corbin is talking about the imaginal (erases the board). And to try and convey the imaginal, I'm going to try and schematically represent it to you. Because if you don't get the imaginal, you don't get what Corbin is talking about. I also would say you ultimately do not get what Jung is talking about when he's talking about active imagination, because you'll just misunderstand active imagination as a purely imaginary experience, as opposed to imaginal experience. And as I'll point out later, Corbin and Jung are deeply influential of each other. Corbin is much more open about that relationship. Corbin talks about and invokes Jung, often critically, but, at least, clearly and explicitly, and with credit. Way more often than I see Jung talking about Corbin, which I think is a criticism I have of Jung.

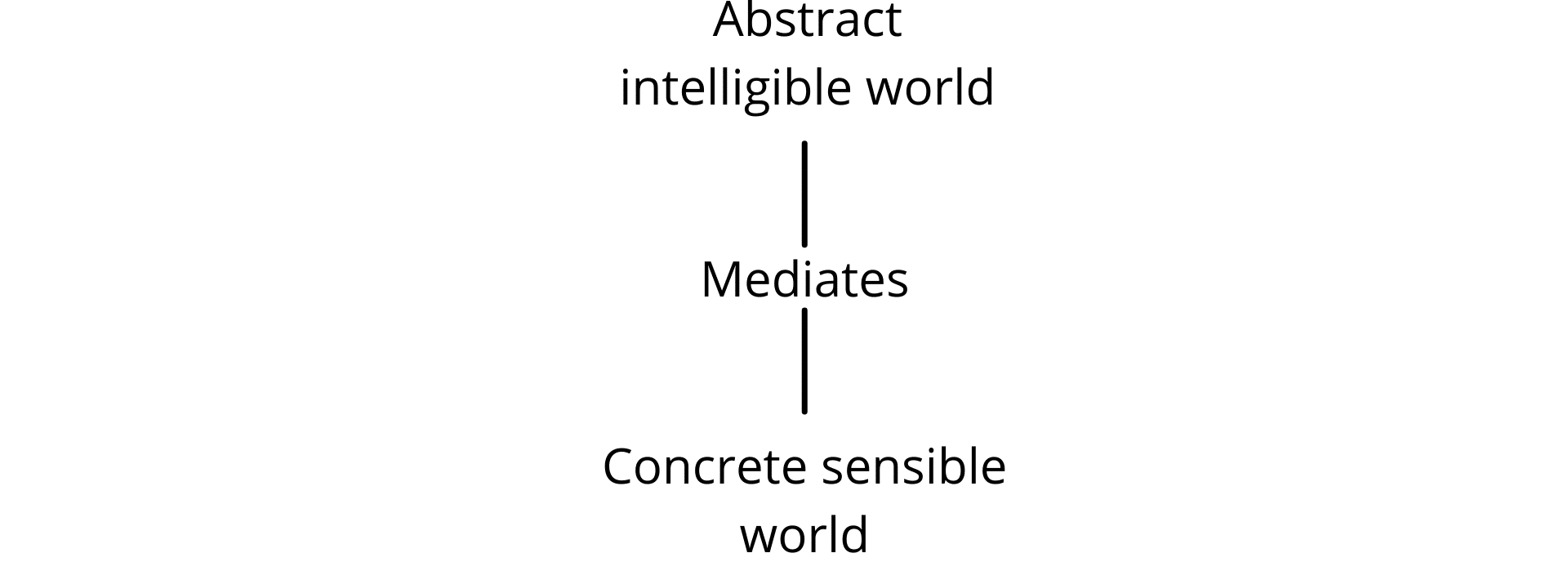

Okay. So let's try and represent this. So, first of all, think of two ways (Fig. 7a) (writes Abstract) in which you sort of try and represent, come into cognitive contact with reality. One is through abstract representations, abstract—the abstract intelligible world (writes intelligible world below Abstract). The world that you get through your intellect, right? So you know, you grasp reality as a mathematical formula or something like that, or, you know, you grasp reality as a purely formal entity. And then in contrast, there is, of course, the concrete and, of course, concrete and abstract are always relative terms, they're not absolute terms. The concrete sensible world (writes Concrete sensible world below Abstract intelligible world) at the bottom here.

Fig. 7a

So one thing the imaginal does is it actually mediates between these two (Fig. 7b) (writes Mediates between Abstract intelligible world and Concrete sensible world). It bridges between them. It allows them to come together in meaningfully structured experience because in my phenomenological experience, of course, there's both an intelligible order that I can abstract intellectually, but that intelligible order also affects the way I come into sensual contact concretely with it.

Fig. 7b

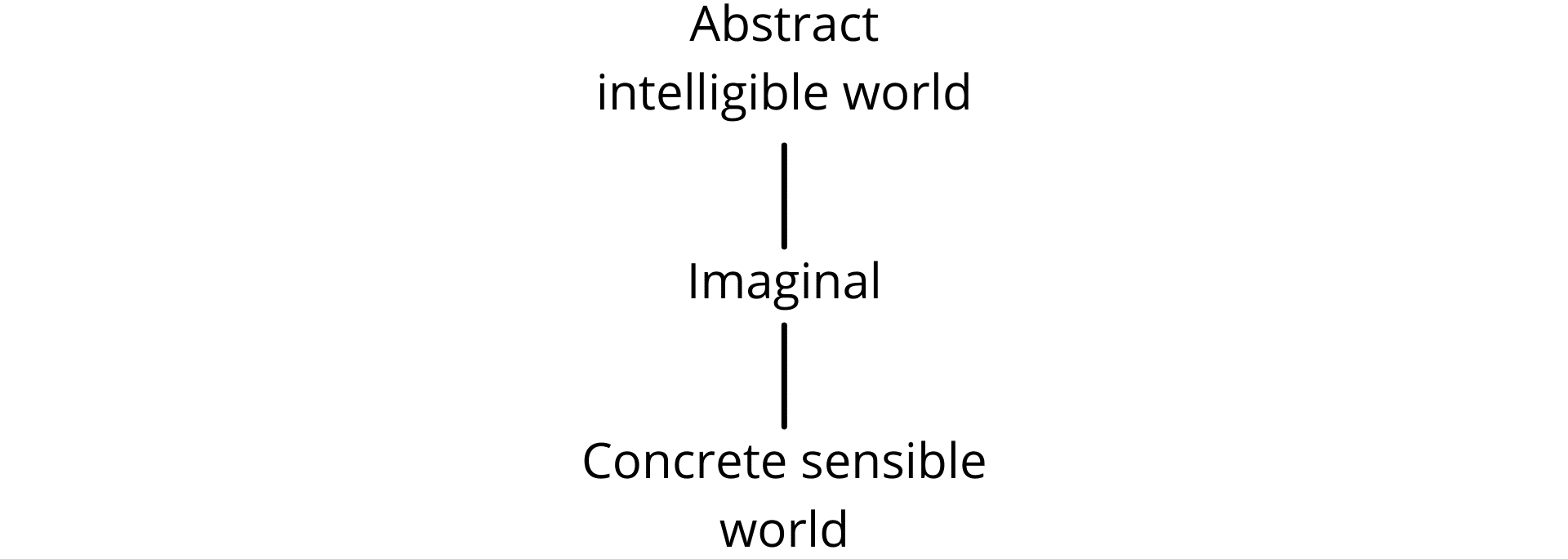

Okay. So the imaginal mediates between these (Fig. 7c) (erases Mediates and writes Imaginal). And one of Corbin's arguments is, and you see what he's doing here. He's arguing that the Cartesian cultural grammar that basically, you know, replicates the axial two worlds, but within us. So here's the world of mind, the abstract intelligible world, pure mind. And the concrete sensible is the world of pure matter. This is the Cartesian division. And what Corbin is arguing is. Yeah, but we've lost the imaginal that bridges between those two worlds between the mind and the material.

Fig. 7c

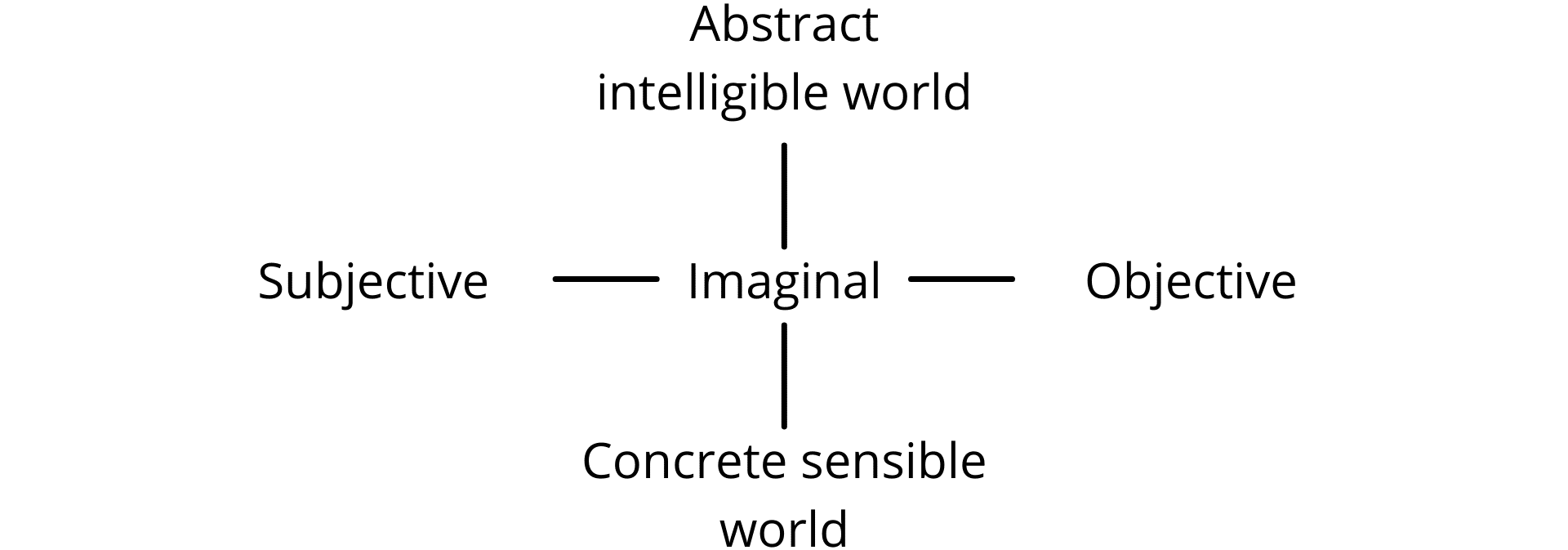

Now, of course, Descartes split things in another way. And the imaginable mediates between those (Fig. 7d) (draws horizontal lines on both sides of Imaginal) and these, of course, they're not the same. That's why I represent them with different axes, but they are not independent. That's why I'm putting them together within the schema. The imaginal also bridges between the purely subjective (writes Subjective to the left of Imaginal) and the purely objective (Writes Objective to the right of Imaginal).

Fig. 7d

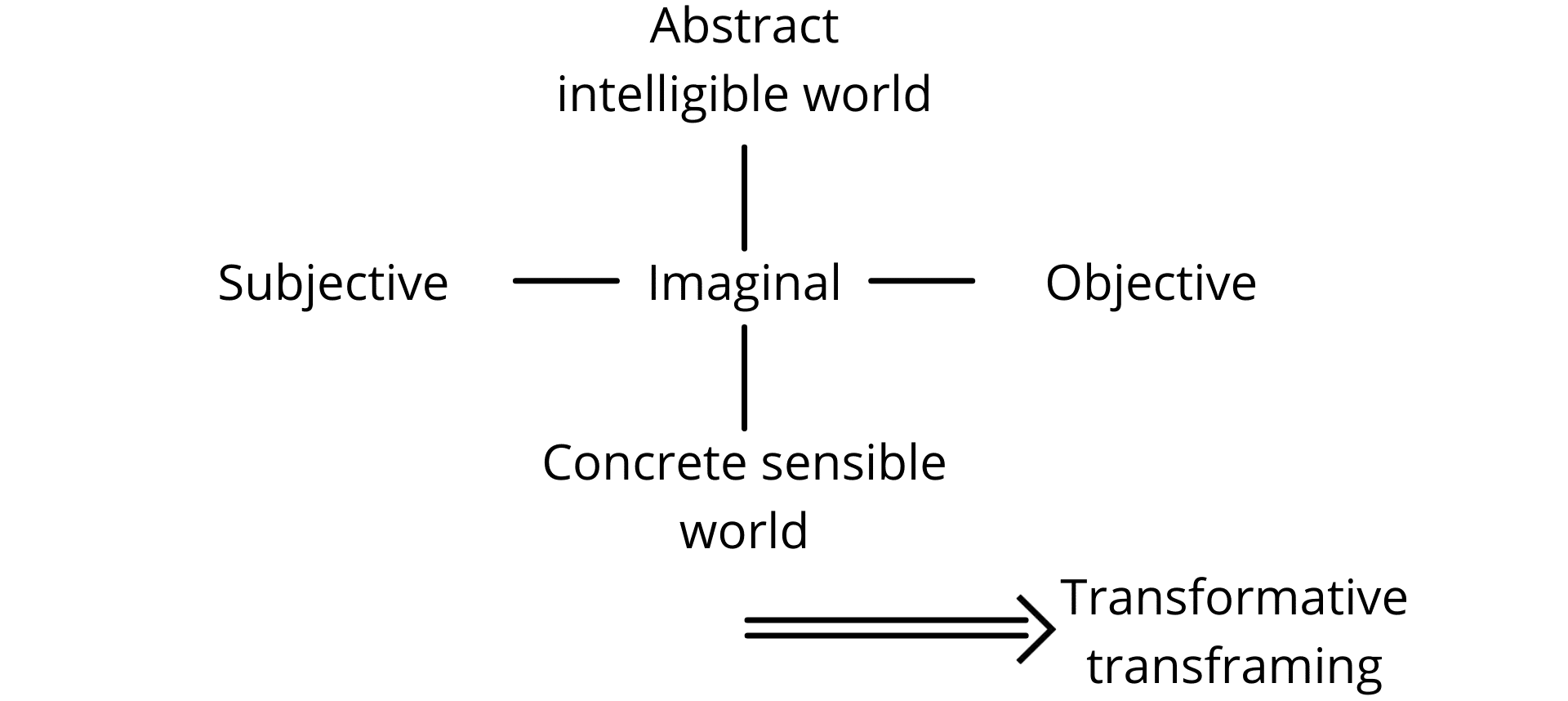

So to use the term I've been trying to develop with you and we saw it all through Heidegger. The imaginal is deeply transjective in nature. So it mediates and it's transjective. And then what you have to do is you have to see this whole thing sort of in motion (Fig. 7e) (draws an arrow pointing to the right below), which I can't draw for you. Because the imaginal isn't a static relation. It's also a constant transformative transframing (writes Transformative transframing). There's a movement to the imaginal. It is vibrant and vital in that way. There's a movement to it.

Fig. 7e

So this is what Corbin means by the imaginal. It's a use of images, but not using them subjectively, using them transjectively. We'll try to come back to that. In a way that mediates, bridges, integrates the abstract intelligible world and the concrete sensible world together. But again, not just statically, but in this ongoing transjective—sorry, in this ongoing transformative transframing.

So because of the centrality of the imaginal to Corbin, Corbin—and he explicitly understood himself as doing this and stated this, right? He was deeply opposed to fundamentalism. And here you can, of course, see the connection to the Persian history I was relating to you. He's deeply opposed to fundamentalism and literalism. Why? Because fundamentalism and literalism, right? First of all, they ratify this. They make it static. And they put things into either the abstract intelligible world or the concrete sensible world, or just in to subjectivity or just in to objectivity. They freeze this and then they fracture it and thereby they completely lose the nexus of the imaginal. And for Corbin, if you lose the imaginal, you lose the capacity for gnosis (Fig. 7f) (writes Gnosis above Imaginal). And then if you lose the capacity for gnosis, you lose the capacity for waking up within the being mode, through aletheia to being and the ground of being in sacredness.

Fig. 7f

This is going to be something we're going to keep seeing. And again, something that Heidegger doesn't make explicit, but it's explicated in Corbin. The deep ongoing criticism to fundamentalism and literalism. It's a deep component of Jung as well. Jung seas, fundamentalism and literalism as the antithetical movement of thought and being in the world to everything he is trying to promote as a response to the meaning crisis. It is also deeply antagonistic to what Barfield is talking about when he's talking about poetic participation.

So we're seeing again a potential way in which we can understand Heidegger's critique of ontotheology because there is a tendency—and all of these thinkers keep pointing to it. If we get into the having mode and we get into ontotheology and we have the supreme being, and we have our propositions about this ultimate being that we can think that the way in which we should be is to have these propositions in a fundamentalist literalist fashion, and we lose all of this.

And what you'll hear is you'll hear the invocation of the symbolic as a dismissive term. Yeah. So that, but yes. Yes, yes, you can read this symbolically, but, you know, it's just symbolic, meaning it has no real relevance or importance to you. Corbin is trying to argue exactly the opposite.

If you have an attitude towards the symbolic, as that is dismissive, then, of course, you have lost the capacity for gnosis, which means you have lost the capacity to remember the forget—like to overcome in aletheia the forgetfulness of being, to come out of the deepest kind of modal confusion.

I see somebody as exemplifying this, although I don't think he's directly influenced by Corbin. I see Jonathan Pageau is trying to bring us back to this gnosis of the symbol. And how we should not be dismissive of it. We should not try and slide it into either a conceptual world or essential world. We should not interpret it as merely subjective or reject it because we can't make it clearly objective for us. Look at all the jecting going on. Subject. Reject.

Okay, so now to try and bring out the imaginal in a way that connects to dasein, your being in the world, 'cause remember your self-knowledge and your participatory knowing of being are interpenetrating and knowing together. I have to bring out something of Corbin. That if you read it and you haven't done all of this work (indicates Fig. 7f), you, I guarantee, will misread it and misunderstand it. And it's a part that's difficult for me because it pushes my buttons in ways that I don't like, which is why I keep reading this stuff. Because I have a tremendous sense that it's pushing my buttons in a way that they need to be pushed so that I could perhaps wear free from them, at least to some degree (erases the board).

Corbin’s Imaginal Understanding Of The Symbol

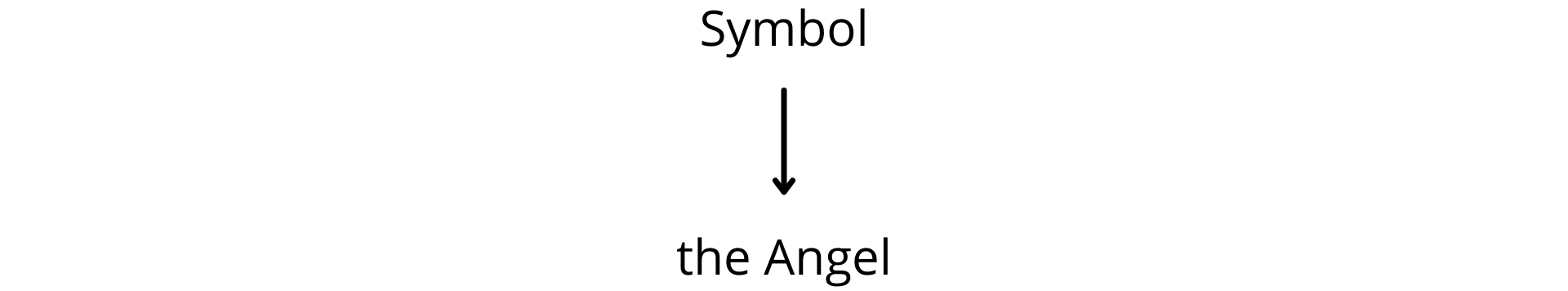

And here's where Corbin is different from Heidegger, where he really does pick up on the sense of sacredness that is going on within the imaginal. Okay. Let's talk about how Corbin understands the symbol (writes Symbol), the imaginal understanding of the symbol, as opposed to the imaginary understanding—the dismissive understanding of the symbol.

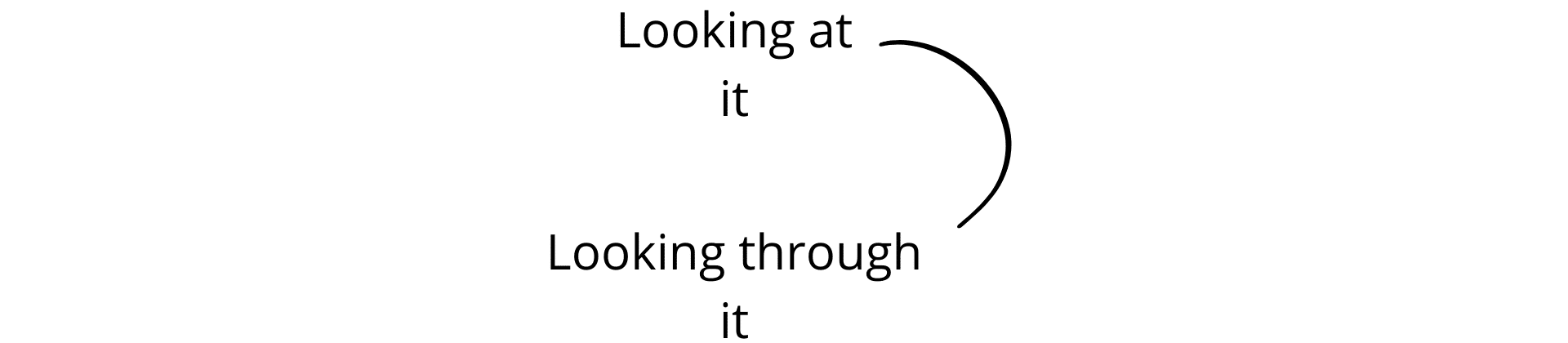

Okay. So what are these features? The feature that was brought out when Chris and I had that excellent discussion, the translucency of a symbol, you look at it, but you look through it in both meanings of the word by means of it and beyond it, like the way I'm looking through my glasses. The symbol is translucent. I can look at it. But I can also simultaneously look through it. And I can put those two into a important dialogue.

Why do I want a dialogue between looking at it and looking through it? (Fig. 8) (writes Looking at it and Looking through it) why is it so important to have those in dialogue with each other? Because that is how the symbol can help you to capture the non-logical identity between your agent arena now in this frame and the agent arena in a more comprehensive encompassing frame (erases the board).

Fig. 8

So symbols are translucent. As I've already argued, they're transjective .Trying to make them either subjective or objective is aligned with a having mode dismissal of how the symbol is trying to challenge you to transcendence. If you—look, if you are not transcending in response to a symbol, you really haven't understood a symbol. If you just treat it as an allegory that you can replace with other literal terms, then you haven't really remembered through the symbol. There has been no aletheia. In your pursuit of the correctness of truth, you have forgotten the aletheia of the symbol. This is why I'm so critical of people who are so dismissive of symbolism.

The symbol is not only transjective, it's trajective. It's putting you on a trajectory of transformation as I was just articulating. The symbol is transformative. Remember the transformative of the inner man, it's transformative you at a fundamental level. And the symbol is ultimately transtemporal transpatial, because it has to do with this movement between worlds, which really isn't a narrative temporal spatial movement, it's an ontological movement between, you know, a smaller frame and a larger frame. I represent it with an arrow, but it isn't movement through space and time. It isn't a narrative change. It's an ontological shift. So I'm trying to pick all of these up. The translucency of the symbol. It's transjective. It's trajective. It's transformative, and it's trans temporal transtemporal, spatial. Aletheia, through the symbol. That's how you do gnosis.

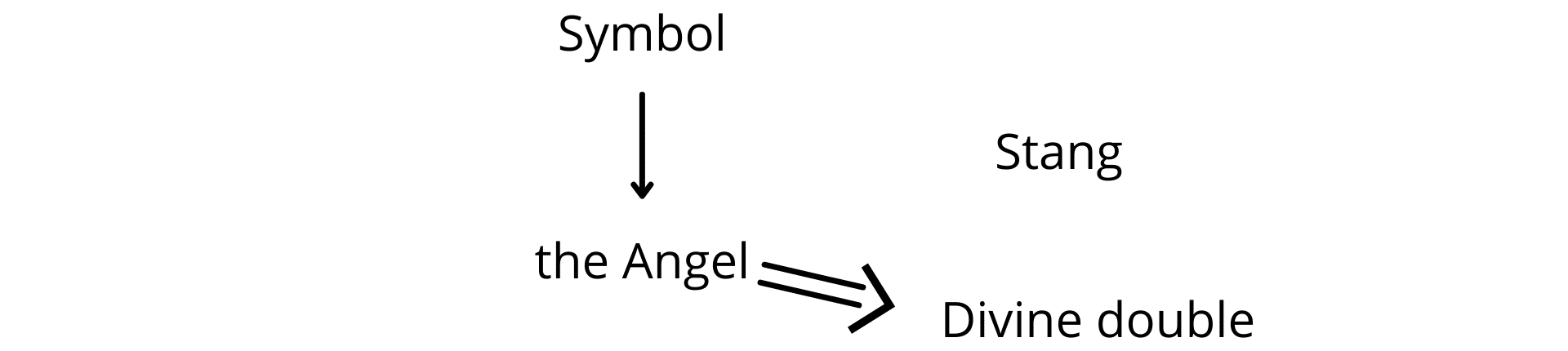

Now let's give the troubling example that is central to Corbin. And I found it disturbing in ways. And some of you will too. And I hope so. What I ask for right now is be patient because I want to unpack this. I don't want to try and be dismissive, but I want to show you that Corbin is not using this notion in a way you standardly will. And like I said—I hesitate to do—so. The most important symbol of this for Corbin is what he calls the angel (Fig. 9a) (writes The Angel below Symbol). And that's why Cheetham puts it in the title of his book. And Avens puts it in the title, the subtitle of his book on The New Gnosis.

Fig. 9a

And soon as I put that up there, many of you are now rolling your eyes as I did. There's a part of me that I can feel there's tension behind my eyes wanting to roll them. Oh no, angels. Oh, silly superstitious idea, you know, cherubs and only new age people that, you know, swing crystals and, you know, the angels and all that stuff. And it's like, oh no, what a disaster.

And I deeply appreciate that. I'm not being dismissive of that. I would say that that's an imaginary understanding of angels. One that Corbett himself repeatedly and deeply rejects. What's he talking about? And why is he using this term? Okay, he's using it because it's a term that is filled, that fills, some of the literature of the Persian Sufism that he reads.

The Notion Of The Divine Double

I want to propose to you an alternative way of understanding this to what our sort of cultural imaginary way of understanding this. Let me go back in our history first (Fig. 9b) (draws an arrow away from The Angel) to try and get a different way of leading into this notion and then take it into some current cutting edge analytic philosophy, believe it or not, and show how that fits well and comports well with the cognitive science we have been doing throughout this response to the four prophets of the meaning crisis.

Fig. 9b

Okay. So, this is—now I'm making use of the seminal work of Stang (writes Stang). Stang wrote a book called the Divine Double, which is a followup to a book he wrote on pseudo Dionysus. And he's written some brilliant articles on pseudo Dionysius that brings all this out. Now. So the book is called the Divine Double (writes Divine double below The Angel) and he's pointing to a particular motif that was prevalent in the Mediterranean world during—and remember we talked about the Hellenistic domocide and thereafter and you have the rise of gnosism and early Christianity. So during this period and across many different groups, you see it within gnosticism, he makes a clear case—and you know, again, some people are gonna, No! He makes a clear case for this motif showing up within early Christianity, you can see it in Manichaeism, you can see it clearly in Neoplatonism and Plotinus, this notion of the divine double. I'm spending time on this because you won't understand Jung also, if you don't understand this divine double.

Okay. So what's the notion of the divine double? It becomes prevalent through the Mediterranean spirituality of the Hellenistic and post Hellenistic period. And I didn't talk about it that much when I talked about the Gnostics and the Neoplatonists because I wanted to talk about it here because here is where I think it belongs. This was the idea. And again, part of this is how this is so antithetical to our way of thinking, especially our decadent romantic way of thinking. So the decadent romantic way of thinking, you know, that sort of goes back to Rousseau is you're born with your true self and you have to be true to your true self and you have to express it. And that's what it is to be authentic. So this has become pervasive in our culture, right?

In this Mediterranean spirituality, the motif is very diff—it's this idea that I'm here and I have a self right now, or they might say a psukhe, a spirit or soul. I have myself right now. But it is bound to the divine double. There's a double of me that is archetypically more important than me and that what I am doing, my true self is actually this divine double, and my spiritual path is to reunite this self with that divine double. And to bring it, bring the two together, then that realization of their interdependence culminates in a kind of mystical union between them.

Now, this is still all very fuzzy language. I'll grant you that. But first of all, notice how this is very interesting. Think—step aside from the mythos for a minute and think about the concept—so you see how this is gnostic, right? Not in the sense of gnosticism, but well, a little bit in the sense of gnosticism, because there's this transgressive—it's trying to break grammar. It's trying to break the grammar of thinking of your true self as something you have. Your identity is something you have that you're born with it. It's in you. And what you have to do is express it authentically. And that grammar is being subverted and transgressed by the idea that your true self is beyond you and you have to aspire to it. And you see there's a bit of a Socratic element there, right? That your true self is something you aspire to, rather than something you have. The true self is something realized through the being mode of self-transcendence, not through the having mode of inner possession.

And so the divine double, it is pervasive. It's a pervasive mythos. And what I'm, first of all, what I recommend is—and I think this is a very fair recommendation. You understand Corbin's use of the angel as a symbolic way of talking about the divine double (draws an arrow from The Angel to Divine double). And you may say, okay, that's great. And I see why it challenges the grammar, but I don't care about this because, all right, I didn't believe in angels and I don't believe in divine doubles. So telling me about angels in terms of divine doubles, what does that gain me? That gains me nothing.

An Aspirational Process Towards A More Angelic Self

Well, I want you to be very, I want to be very careful here. I want to start a problem. I want to start you on a deep analysis of this, right? Let's put aside the mythos, let's put aside the metaphysical claims, right? And let's focus in on this very process of aspiration towards a better self, towards a more angelic self, right? Because it goes back to the Socratic project, but you can also see it in the depths of our current—sorry, not, that's too broad (erases the board). Sorry. You can see, you know, this process of aspiration towards a greater, better fuller self is, of course, all the way through Maslow. It's all the way through Jung. This aspirational process is central to a lot of the mythos that we have about talking about how we are going to normatively improve, not our situation, but ourself.

So is the divine double a crazy idea? Well, in one sense, it is. Again, if you just sort of literalize the mythos into some sort of axial two world mythology, a metaphysics. Sure. But maybe it's not a crazy idea if we go back and try to ask this question. Instead of asking the question—look, this is what I meant about real dialogue, philia sophia, not philia nikia. Instead of asking the question, should I believe that? First, ask yourself the question. Why did so many different groups of people in that world believe it? What was going on there? What was it doing? And here is where I think I can immediately invoke the important work which I have discussed repeatedly throughout this entire—the entire argument in this entire series, the important work of LA Paul and transformative experience. And that was bound up with the way we talk about gnosis.

Now I alluded to somebody else's work. Work that was influenced and from the same area, sort of—I don't know what to call it—school? As LA Paul's work. And this is the really important work of Agnes Callard and her book is entitled Aspiration. And she's arguing for a neglected form of rationality that is best understood through aspiration.

And rationality? What? Remember, I don't use rationality to mean management of just the logical management of argumentation. Rationality means any systematically reliable internalized psychotechnology that reliably and systematically affords you overcoming self-deception and affords you cultivating enhanced connectedness, enhanced meaning in life. That's why the notion of rationality I've argued for is bound up with the—it can culminate, it could point towards the cultivation of wisdom.

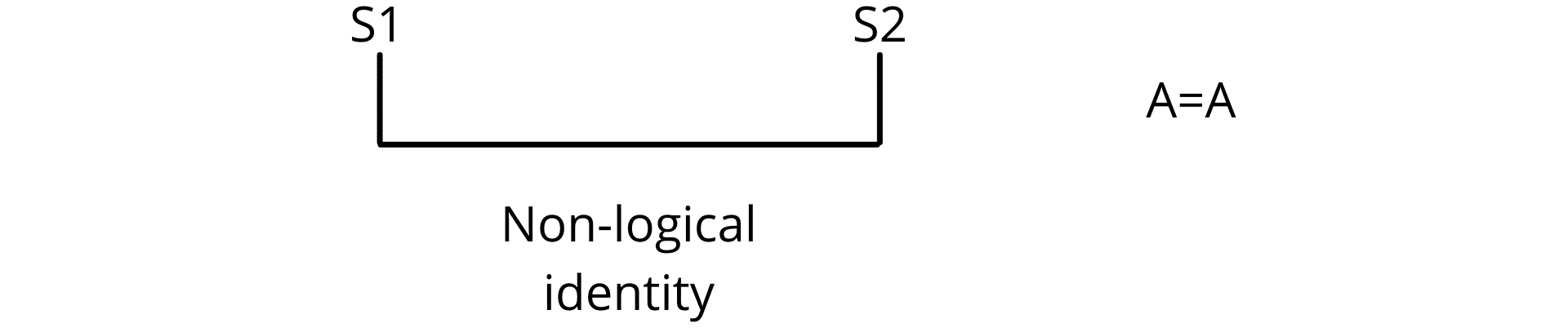

So there's, let's talk about yourself before the transformation or before you launch into the aspirational process and the self afterwards,S1 and S1 (writes S1 and S2). (Text overlay appears saying, 'This has nothing to do with the S1/S2 distinction between kinds of cognition). Now, LA Paul tends to represent this as a much more sort of rapid transition. And I think there's important truth in that, the insight. Whereas Callard is representing it much more, not incrementally, that's not the right word, but much more developmentally having a much more extended developmental trajectory. And you can reconcile those, I think, quite readily by seeing qualitative development as a sequence of insightful transformations. So I don't think there's any deep inconsistency here.

Okay. So what's the problem here? Well, as I've already pointed out (Fig. 10a) (draws a line connecting S1 and S2) with any genuine quantitative—sorry, I used exactly the wrong word. I apologize. Because I've pointed out with any genuine qualitative development—quantitative elements, you just get, sort of, more things, more beliefs, more experiences. Qualitative development is why I am so different in kind from that kid that was born in Hamilton. It's a fundamental difference of competence of what I can know and what I can do and what I can be rather than just how much.

Fig. 10a

So, I've already pointed out that you have an issue here of non-logical identity (Fig. 10b) (writes Non-logical identity under S1 and S2). Okay. So this is not an identity relation that that can be captured by the fundamental identity theorem in logic that A is identical to A (writes A=A) meaning that they share all the same properties. We do not. John in Hamilton and John in Toronto. John and Hamilton then, and John and Toronto now, we are not, we are not this (indicates A=A).

Fig. 10b

We have a non-logical identity and I've brought that out. And how much gnosis is about the difficulties, of trying to overcome the difficulties that this poses (indicates Non-logical identity). Because of this non-logical identity. And I'm not going to repeat these arguments, go back and look at them when I talk about gnosis. We cannot reason our way through this. We cannot infer our way through this. And Callard is deeply in agreement with this aspect. You cannot deliberate your way through it. You can not decide your way through it.

So what is the nature of the relation, right? Well, Callard thinks it's aspirational. It involves what she calls aspiration. But she's at pains to point something out that LA Paul doesn't, which I think is very important. You can't, if you don't include this process (writes Rational beside Aspirational) as part of what you mean by this term, you're going to get into a deeply self-refuting position. Because my relationship to rationality and my relationship to wisdom are aspirational.

I am aspiring to become rational, precisely because I am not currently that rational. And if the aspiration to rationality is not part of rationality, you're getting into a weird kind of self-refutation. The aspiration of rationality is constitutive of the ongoing process of being rational. And therefore it must be included in your notion of rationality and notice how we're getting back towards the platonic idea of the deep interpenetration of love and reason. Took a long time, eh? It took a long time to circle around back to that. Of course, this is also the case for wisdom.

It's also—look, think about this this way. One of the things I need to do to become rational is to become more educated. And, but Callard argues explicitly, a genuine educa—well, there's different meanings to that word now. One is just the accumulation of facts and skills and stuff like that.

But for many, and this is what—this was supposed to be, maybe it still is, the defining feature of a liberal education. Liberal, liberal, to liberate you. Gnosis. To save you. To liberate you from existential entrapment. Our liberal education is designed to make you into a better self, a better person, which is why it seems so useless to people who want to manipulate and control you. Think about that when you side with, Oh, liberal education silly, you're a—your side. I think you're getting on the wrong side because we're losing something there. Right? So a liberal education, and this is what it classically meant when you go back into the middle ages is gnosis. It's aspirational. And you don't know what it's going to be like. Remember all that stuff about LA Paul?

So let me leave you with the example from Callard, and then we'll come back and talk about this in the next episode and expand this whole. What is that? What am I trying? What am I leading you towards?

I'm leading you towards that this (indicates S1 and S2) is the relationship between the existing self and the divine double. Or another way of perhaps putting it the divine double is a symbol in Corbin's sense that allows you to move from yourself now to yourself then to the better self.

One of the examples that Callard gives in aspiration is and think about how this fits in with a liberal arts education. Somebody who wants to come to appreciate music and notice a play and how that word appreciation means both understanding and a gratitude. It has a connotative emotional aspect. It has a denotative conceptual aspect of—cognitive aspect, I should say. I will understand music.

So I want to, let's say I don't currently get classical music. But I have an inkling that's really important. I think that, you know, Charles Williams and Barfield and Tolkien and CS Lewis called themselves the inklings. I have an inkling that there's a self and a world there. Remember we talked about the person trapped in this world, but a sense that there might be a better self and a better world over there?

I have an inkling that I should like classical music. But I don't currently like classical music. I have to come to be the kind of being that appreciates classical music. How do I do that? How do I bridge from me now not appreciating, not getting, not liking, not enjoying classical music to somebody who can sincerely say I love classical music. I really get it now. How can I?

We use this phrase and notice how it's so rich and resonant with, you know, contact epistemology. But now I have a taste for music. I've an acquired taste for it. Let's get behind the metaphor. How is it? And notice when you taste something, you're putting it into—you're putting it into your being. It's not only contact. It's even consumption, not in the having mode sense, but taking it deeply in, right. What is it to move that way?

What I'm trying to show you is that Corbin's talk about the angel is a way of him invoking and bringing into activity, all of this stuff about symbolism that we've talked about and integrate it with this process of aspirational rationality, that is so central to self-transcendence. And so central to us becoming more rational and more wise.

Thank you very much for your time and attention.

- END -

Episode 48 Notes

To keep this site running, we are an Amazon Associate where we earn from qualifying purchases

Aletheia

Aletheia is truth or disclosure in philosophy.

Henry Corbin

Henry Corbin was a philosopher, theologian, Iranologist and professor of Islamic Studies at the École pratique des hautes études in Paris, France.

Gnosis

Gnosis is the common Greek noun for knowledge. The term is used in various Hellenistic religions and philosophies. It is best known from Gnosticism, where it signifies a spiritual knowledge or insight into humanity's real nature as divine, leading to the deliverance of the divine spark within humanity from the constraints of earthly existence.

Robert Avens

Book Mentioned: The New Gnosis – Buy Here

John Caputo

John David Caputo is an American philosopher who is the Thomas J. Watson Professor of Religion Emeritus at Syracuse University and the David R. Cook Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Villanova University.

Book Mentioned: The Mystical Element In Heidegger’s Thought - Buy Here

Angelus Silesius

Angelus Silesius, born Johann Scheffler and also known as Johann Angelus Silesius, was a German Catholic priest and physician, known as a mystic and religious poet.

Owen Barfield

Arthur Owen Barfield was a British philosopher, author, poet, critic, and member of the Inklings

Meister Eckhart

Eckhart von Hochheim OP, commonly known as Meister Eckhart or Eckehart, was a German theologian, philosopher and mystic, born near Gotha in the Landgraviate of Thuringia (now central Germany) in the Holy Roman Empire.

Paul Tillich

Paul Johannes Tillich was a German-American Christian existentialist philosopher and Lutheran Protestant theologian who is widely regarded as one of the most influential theologians of the twentieth century.

Ontotheology

Ontotheology means the ontology of God and/or the theology of being. While the term was first used by Immanuel Kant, it has only come into broader philosophical parlance with the significance it took for Martin Heidegger's later thought.

Physis

Physis is a Greek philosophical, theological, and scientific term, usually translated into English — according to its Latin translation "natura" — as "nature".

Book Mentioned: Heidegger and Asian Thought - Buy Here

Book Mentioned: Heidegger’s Hidden Sources - Buy Here

Tao Te Ching

The Tao Te Ching is a Chinese classic text traditionally credited to the 6th-century BC sage Laozi, also known as Lao Tzu or Lao-Tze.

Rumi

Jalāl ad-Dīn Mohammad Rūmī, also known as Jalāl ad-Dīn Mohammad Balkhī, Mevlânâ/Mowlānā, Mevlevî/Mawlawī, and more popularly simply as Rumi, was a 13th-century Persian poet, Hanafi faqih, Islamic scholar, Maturidi theologian, and Sufi mystic originally from Greater Khorasan in Greater Iran.

Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the second century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion.

Gary Lachman

Gary Joseph Lachman, also known as Gary Valentine, is an American writer and musician.

Book Mentioned: Lost Knowledge of the Imagination - Buy Here

Tom Cheetham

Book Mentioned: The World Turned Inside Out – Buy Here

Book Mentioned: Imaginal Love – Buy Here

Book Mentioned: All The World An Icon – Buy Here

Manichaeism

Manichaeism was a major religion founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani, in the Sasanian Empire.

Charles M. Stang

Book Mentioned: Our Divine Double – Buy Here

Book Mentioned: Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite: "No Longer I" – Buy Here

L.A. Paul

Laurie Ann Paul is a professor of philosophy and cognitive science at Yale University. She previously taught at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Arizona. She is best known for her research on the counterfactual analysis of causation and the concept of “transformative experience.”

Agnes Callard

Agnes Callard is associate professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago. Her primary areas of specialization are ancient philosophy and ethics.

Book Mentioned: Aspiration: The Agency of Becoming – Buy Here

Other helpful resources about this episode:

Notes on Bevry

Additional Notes on Bevry