Ep. 50 - Awakening from the Meaning Crisis - Tillich and Barfield

(Sectioning and transcripts made by MeaningCrisis.co)

A Kind Donation

Transcript

Welcome back to Awakening from the Meaning Crisis.

So last time we looked in depth at Corbin and Jung. And I tried to draw out very deeply the notion of the relationship to the sacred second self. I launched into sort of mutual criticism between Corbin and Jung and brought in some Buber along the way.

And then I pointed to somebody whose work, also deriving from Heidegger integrates aspects of all of these together in kind of a profound way. Tillich is deeply influenced and aware of what he calls depth psychology, the kind of psychology in Jung. He, of course, is deeply aware of Heidegger. I don't know, I don't think that Tillich was aware of Corbin, but he is deeply aware of the symbol in an imaginal rather than in a merely imaginary way.

Tillich takes the meaning crisis seriously. He writes, perhaps, his most well-known, and I think it's a masterpiece book, The Courage To Be as a response to the meaning crisis. Like Jung and Corbin, and for very related reasons, he's deeply critical of literalism and fundamentalism throughout. But he takes it deeper, as I mentioned, he really deepens it in terms of Heidegger's critique of ontotheology. And he becomes critical of literalism and fundamentalisms as forms of idolatry in which we are attempting to have rather than become.

So there are some excellent books on the relationship between Jung and Tillich. This is a series of ongoing work by John Dourley. I recommend two books to you, The Psyche as Sacrament, which I have tweeted about in my book recommendations. I would also recommend his later book, Paul Tillich, Carl Jung and the Recovery of Religion. But make no mistake. Dourley is not talking about a recovery in a nostalgic sense. He writes another book called, Strategy For A Loss Of Faith, where he is trying to get beyond classical theism. And so I recommend Dourley's work as a comprehensive way of bringing about a deep dialogue and a kind of integration between Jung and Tillich.

En-couragement

Okay. So Tillich says the main response to the meaning crisis and here's how Tillich is not just theorizing. He is trying to give us guidance on how to live. And let's remember that this really matters because of, you know, the way Tillich resisted the Nazis. Because what Tillich talks about in The Courage To Be is courage.

Now he's careful to note that this is a kind of existential courage that ultimately allows us to confront and overcome meaninglessness in its depth. But also, of course, to more practically respond to, you know, perverted responses to the meaning crisis itself like Nazi-ism and its Gnostic nightmare.

This process of encouragement. Now he is like Aristotle. He's not talking about something as simple as just bravery facing danger or fortitude, the ability to endure. No. For Tillich, courage is a virtue. There's something of wisdom in courage. Courage involves within it that central feature of wisdom, which is seeing through illusion into reality. The brave person faces danger, but that's all we can say about them. The person with fortitude endures difficulty, but that's all we can say of them. The courageous person sees through the illusion and the distortion of fear or distress to what is truly good and acts accordingly.

Faith As Ultimate Concern

So what is this seeing through and how does it help us confront the meaning crisis? So this notion of seeing through, seeing to the depths, as Tillich often says, is related to Tillich's notion of faith (writes Faith). And here, notice how we're circling back around. And this isn't really a circle because Tillich's notion of faith is not the assertion of propositions to believe. He is circling back to the ancient Israelite Hebrew notion of the Da'at. And now we can add that that participatory knowing, in a course of being, is an aspirational process.

Tillich understands faith as ultimate concern (Fig. 1a) (writes Ultimate Concern). That which concerns us ultimately. His notion of idolatry is to treat something that could be a symbolic icon through which you articulate and develop your ultimate concern. You transform that into idol, an object to have and possess to control and manipulate. And you, thereby, are using the machinery that it's appropriate for ultimate concern for something that is not ultimate.

Fig. 1a

What is ultimate concern? What is concern? Well, when you're concerned about something, you care about it, but you're also coping with it. You're committed to it. You're involved in it. It encompasses you, even though you are being involved in and through it. It is deeply perspectival and participatory. That's what he's trying to get at. And it is aspirational and it is open ended. It points towards the inexhaustibleness of the ground of being.

So, of course, Tillich's notion is directed at Heidegger's notion of dasein, right? This concern that dasein is the being whose being is in question and therefore by our perspectival participatory knowing of our being, we come into deeper contact. But remember for Heidegger that requires a deep remembering, an overcoming of our forgetfulness, an aletheia. We have to have the ontological wonder towards the ground of meaning. The ground of being. This leads into Tillich's notion of God (writes God), which, I'm going to try and propose to you, is transgressive of classical theism in important ways, without it being identifiable with atheism in important ways.

So Tillich understands God as an icon, as opposed to an idol. As an imaginal symbol for the ground of being. God symbolizes the ground of being and therefore God is no kind of being. There is a no-thingness (Fig. 1b) (writes No-thingness) to God, God is no kind of thing. And any attempt to reify to think of God as a thing is, for Tillich, a form of idolatry.

Fig. 1b

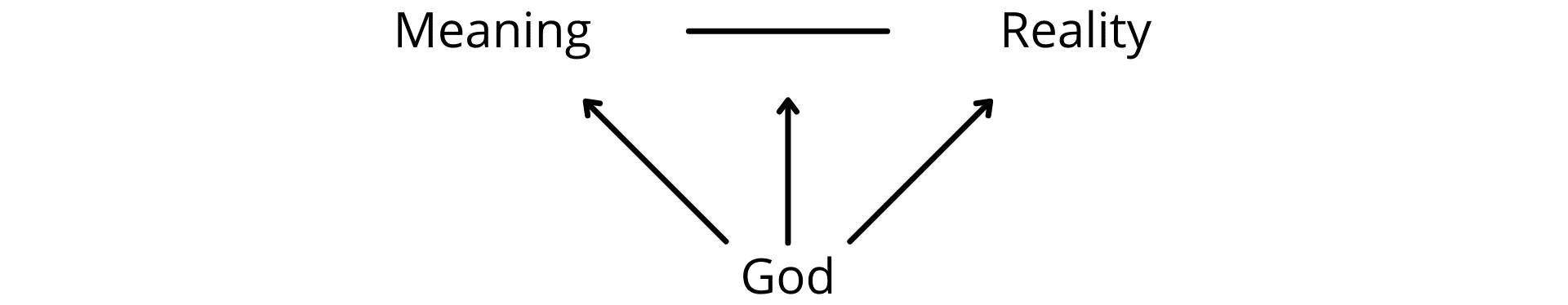

So here's what I'm trying to get you to see what Tillich means. Here's meaning (Fig. 2) (writes Meaning). And here's reality (writes Reality). And here's the relationship between them (draws a line between Meaning and Reality). God is the simultaneous grounding of all of these (writes God below and draws three arrows to Meaning, the line, and Reality).

Fig. 2

You can see the influence of Heidegger here, right? God is the ground of the meaning making, of reality and of the relationship between them. And any attempt to limit God to any one of these three components, just to the meaning, just to the reality, just to the relationship between them is, for Tillich, a profound kind of idolatry. This is why literalism and fundamentalism are so pernicious to him.

So ultimate concern, if we allow ourselves to truly come into question and quest in a wondering way. If we participate in an aspirational trajectory motivated by ultimate concern, this puts us into a resonant relationship. This gets to what is known as Tillich's method of correlation (writes Method of correlation). This is how he saw himself doing theology.

I know it's kind of odd for a, you know, naturalistic, cognitive scientist to be talking about theology again. But I think we've gotten to a place where that seems to you as a viable and valuable thing to do.

Method Of Correlation

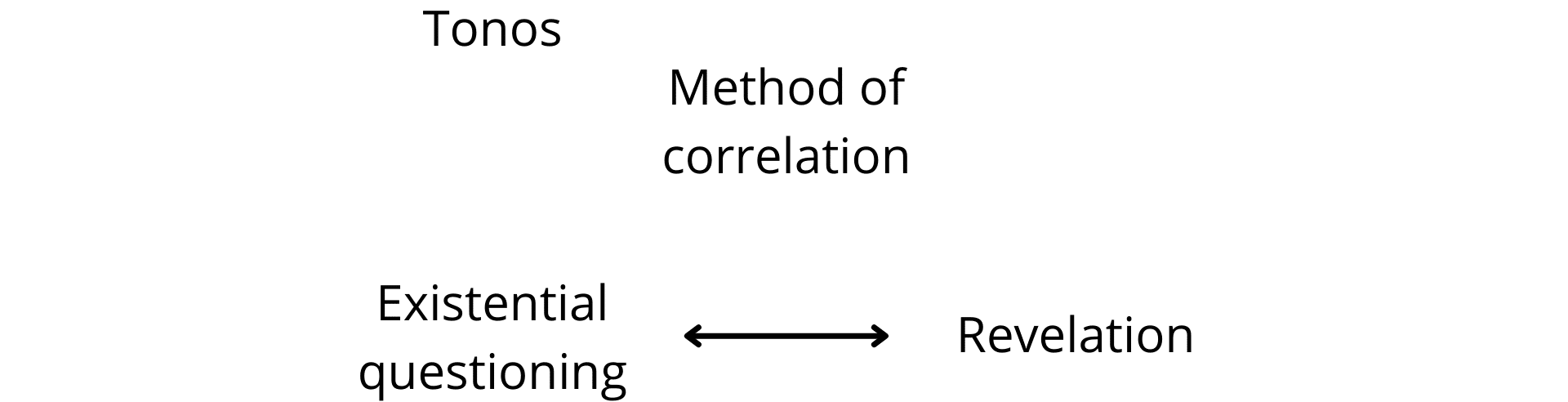

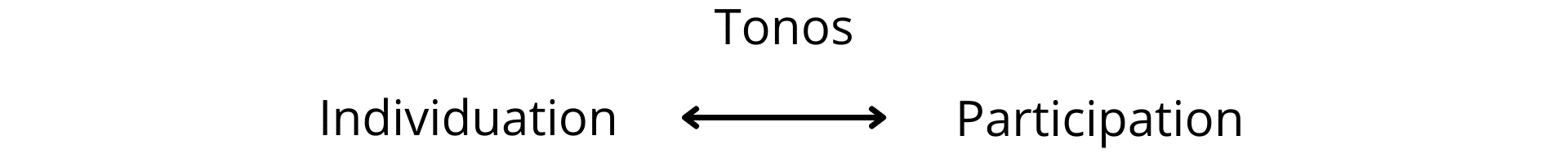

What's the method of correlation? That there is always this ongoing tonos (Fig. 3) (writes Tonos)—there's polar tension, which we talked about earlier—between existential questioning (writes Existential questioning) , understood as existential questing, and what Tillich calls revelation the way the depths of reality reveal themselves (draws a double-headed arrow and writes Revelation).

Fig. 3

These are always resonating with each other. The revelation has to fit the existential questioning, but the existential questioning has to fit itself. So there's a mutual dynamic fittedness going on—no, that's not, I want to get a verbal rather than an adjectival. Yeah—there is an ongoing resonant fitting, mutual fitting togetherness of the essential questioning and the revelation.

You can see how this is very similar to anagoge. I think one of the problems that I see in a lot of interpreters of Tillich—and I've read quite a few—is that this method has been, this correlational method has been misunderstood as just propositional theology. That this is all about, you know, propositional proposals—listen to the word proposition. Propositional proposals. And then what we get are we get other propositions from the sacred texts, the Bible, and what we're doing is we're putting the propositions of theology into concordance with the propositions of the Bible. And I think that's to fundamentally trivialize Tillich to not get at the depths, the existential depths of the method of correlation.

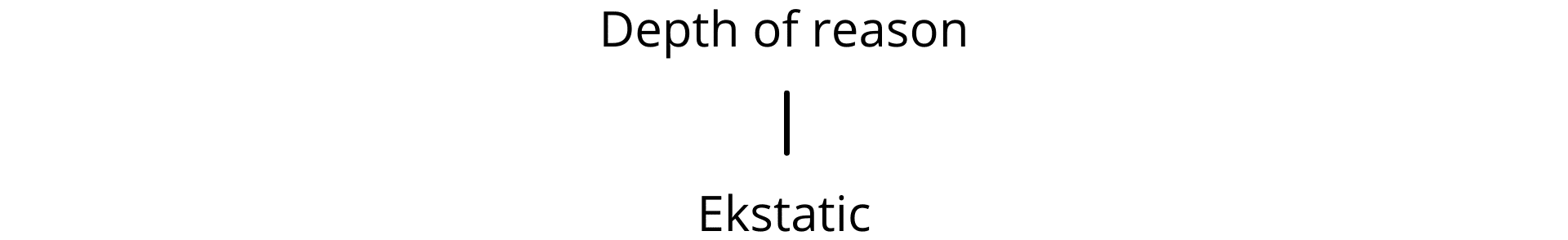

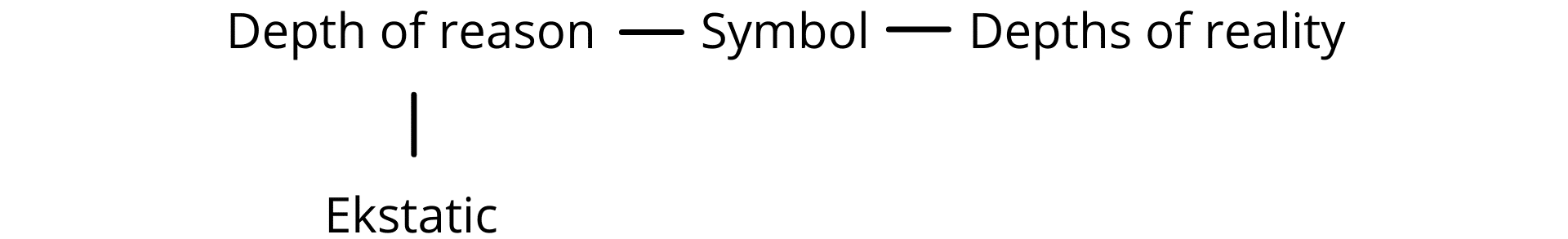

I want to propose a different way of understanding that that picks up on the tonos and takes us towards God as the ground of being as I've represented it to you. (erases the board) And this is the language Tillich uses. Tillich talks about the depths of reason (writes Depth of reason). This is a Platonic notion. That which makes reasoning possible. It's all the relevance realization machinery, I would argue. The recursive machinery of rationality, the aspirational rationality, that Callard talks about. All of those things, the depths of reason.

And Tillich talks about that we have an ekstatic relationship (Fig. 4a) (writes Ekstatic below Depth of reason) ecstasy, right? The depths of our reason we're standing beyond ourselves. It's the depths of the psyche, but not just in the psychological way that Jung means, but also the depths of the grounding depths of our rationality.

Fig. 4a

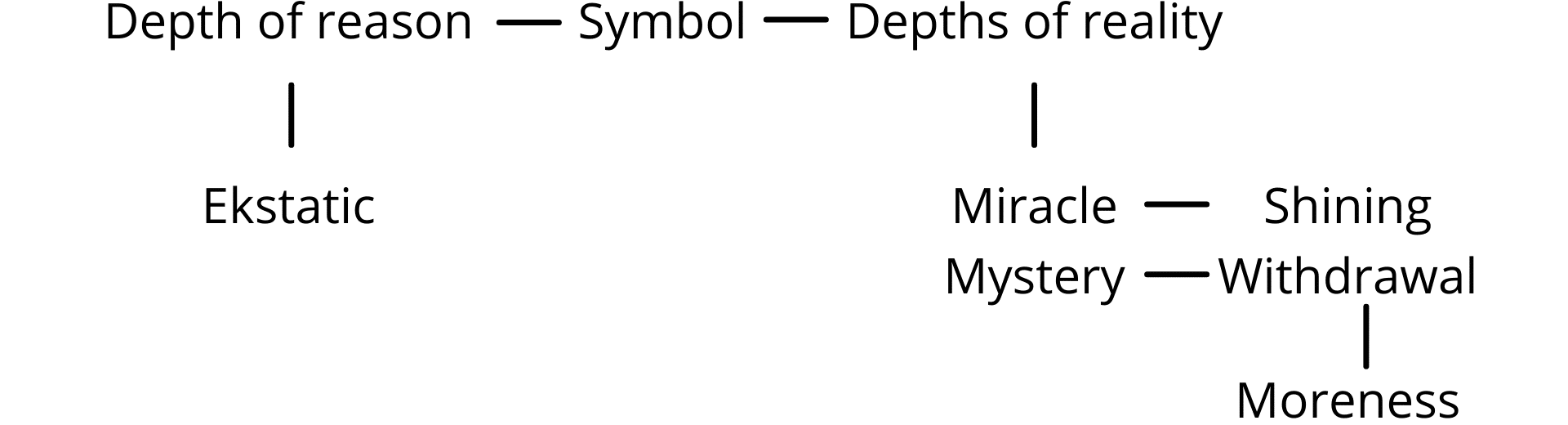

And then what stands between is a symbol (Fig. 4b) (writes Symbol beside Depth of reason) in Corbin's imaginal sense. And Tillich is so clear about that. The symbol to the depths of reality (writes Depths of reality beside Symbol). So in the psyche, the depths of reason are experienced as ekstasis, self-transcendence moving beyond myself. So crucial to aspiration, genuine transcendence in genuine self-transcendence.

Fig. 4b

The depths of reality Tillich talks about, he uses two words here. He uses, sometimes, he uses the word miracle (Fig. 4c) (writes Miracle below Depths of reality) and this was probably like, I know for me, that's like, Oh no, right? And that's like angel, because this looks like magic in the pejorative sense of the word. He also talks about it as mystery (writes Mystery below Miracle). I think there's two ways using some Heidegger, which is fair because of the Heideggerian influence on Tillich. We can think of miracle as that aspect of being that we've talked about as the shining (writes Shining beside Miracle). And we can talk about the mystery as that aspect we've talked about as like the withdrawal into the moreness (writes Withdrawal and Moreness beside Mystery).

Fig. 4c

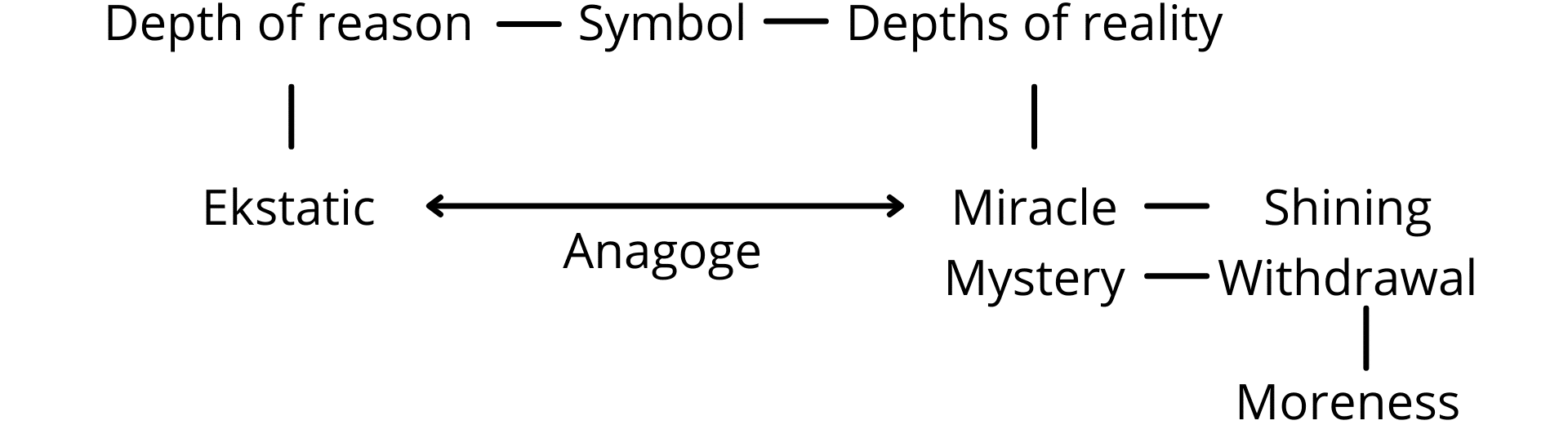

The combinatorially explosive depths of reality. And, of course, I tried to argue through Heidegger and through Corbin, especially through Heidegger how these two (indicates Shining and Withdrawing) are interaffording in our sense of realness. And then the idea, the method of correlation is basically, as I suggested to you, the anagoge (Fig. 4d) (draws a double headed arrow between Ekstasis and Miracle & Mystery and writes Anagoge) between the ekstasis, as we resonate with the depths, the grounding and formative depths of reason are resonating with the grounding informative depths of realness and they are anagogically cycling together.

Fig. 4d

So you've heard all of this before, but let's quickly repeat it for Tillich. The symbol is much more than a sign. Chris Mastropietro in his first discussion with me brought this out excellently. And that is clearly the case in Tillich. Symbols are participatory. The symbol opens up levels of reality otherwise closed to us. The symbol opens up levels of ourselves, otherwise closed to us, and it does this in a mutually affording resonant fashion. Symbols are not made by us. And this, of course, is something we've talked about before and we'll see it come out when we get to Barfield.

They are self-organizing and they grow out of the unconscious within us and the unconscious without us. Symbols have a life. They can die, they can be born, they can live, they can die. Tillich worries that many of the symbols in Christianity are dying. And that fundamentalism and literalism are an inappropriate way of trying to hold on to them and keep them alive rather than affording the rebirth—sorry, that's the wrong word—affording the new birth of a new symbol that brings back the relationship, the resonant relationship that the old symbol possessed. Perhaps, this is what Jonathan Pageau means when he feels that Christianity in the meaning crisis is going through a profound death and rebirth of its symbolic structure.

For Tillich symbols have a surplus of meaning. There is a moreness to them. If they're not resonating with moreness, they're not symbols. They have a numinous character grounded in the resonant depth of mind and reality, and therefore symbols are deeply transformative. They're deeply transjective, their deeply translucent, et cetera, et cetera. So this is why correlation is not just propositional theology. If you're not undergoing a profound transformation, you're not doing Tillich's correlational method.

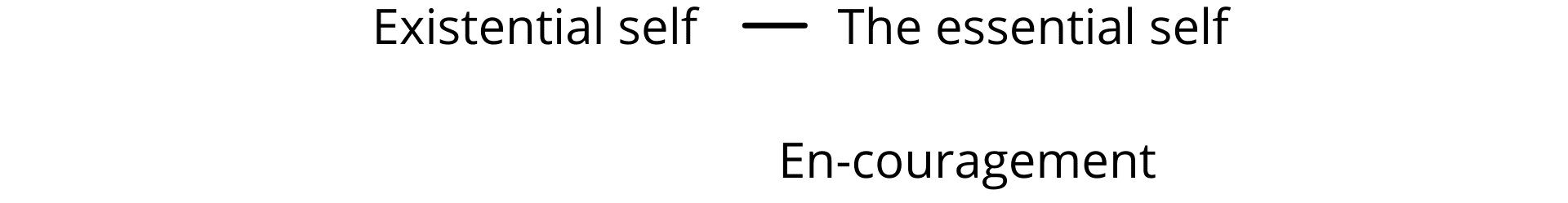

So [-] how is it realized symbolically? It's realized symbolically—and you're going to see—okay, how is all of this, how is it realized by you? (erases the board) Both senses of the word realized, taken into your frame, but also actualized in reality. How is this transformative power of the symbol realized? It's realized in the relationship between the existential self (Fig. 5a) (writes Existential self) and the essential self (writes The essential self beside Existential self). And do you see what's coming here?

Fig. 5a

This is the relationship to—the relationship of the current self (indicates Existential self), the self in existence to the sacred second self (indicates The essential self). The essential self is the self in the fullness of being. Remember Plato's anagoge. The self in its fullness of being that is capable of recognizing through conformity, the fullness of being in the world.

This relationship that Tillich is pointing to use, we can use language we've carefully worked out together. This relationship between the existential self and the essential self is aspirational. Tillich, like, he repeatedly talks about how the essential self is ahead, of course, not causally ahead. Normatively ahead. The essential self is ahead, not causally, but normatively. It's ahead of the existential self. The essential self beckons the existential self towards fulfillment. It's constantly tempting, if you'll allow me this language, the existential self to a better way of being. It's trying to tempt it out of the world in which it might be existentially trapped. This is the gnosis within Tillich. So the sacred second self.

And for Tillich, this is bound up with like, you know, when Saint Paul was talking about, you know, remember when we talked about agape? I used to be this way, I acted like a kid. Now here's the new way. I act like a man. This is the way of agape. So my salience landscape is sophrosyne, it naturally self-organizes to constantly tempt me towards the good. And Tillich wrote a very excellent little book on agape. I highly recommend it to you.

So this aspirational, transformative journey of encouragement, literally embodying courage. Encouragement (Fig. 5b) (writes En-couragement), right? Encouragement gets us to confront seriously meaninglessness. Now In The Courage To Be, Tillich goes through various historical developments. In the ancient world, the meaningless is confronted in our being as the finitude of our being. And he talks about how the Stoics responded to that. And then he talks about during the Christian period and especially during the Protestant reformation. Because Tillich is deeply influenced by Lutheranism in a very critical way though, of course. And the meaningless is confronted within our self-knowing as guilt. And he talks about the Protestant reformation as an attempt to seriously respond to the issue of guilt. And then now in our current period, right, we are experiencing meaninglessness in our self as despair, and he represents that. He says that is being represented by the existentialists.

Fig. 5b

Of course, Heidegger—sorry, Tillich is writing in the period of the fifties and sixties when existentialism was still more prevalent. We, of course, can talk about things following on existentialism if we have more time, like postmodernism and other things that are represent—not representatives [-]—discussing and articulating a deeper way in which we are embodying the meaning crisis. But nevertheless, you can follow this trajectory through The Courage To Be. You can go through the Stoics. You can go through the Protestant Christians. You can go into the existentialist.

The No-Thingness Of God

And this trajectory leads us to a position beyond all three. The position that Tillich is arguing for which he calls the response to faith. Remember faith is Da'at for Tillich. It is not the willful assertion of belief. And here's the thing. And this is why idolatry is so pernicious for Tillich. The no-thingness of God coming to really encounter the no-thingness of God is central to this notion of faith.

The no-thingness of God takes into itself the no-thingness that's—sorry, no,, I misspoke. The no-thingness—let me change how I'm pronouncing these terms because it will help. The no-thingness of God takes into itself the nothingness of meaninglessness and it overcomes it. The no-thingness of God has a transformative power over the nothingness of despair. So this is the notion of a fundamental aspect, identity shift.

And here's where if I had time and I'll bring it out when I get into this other series. I would talk about Nishitani because his book of Religion and Nothingness is an extended, philosophical, profound examination of this fundamental aspect shift, identity shift.

Remember what an aspect shift is. Remember the Necker cube, right? (Fig. 6) (draws a 3D outline of a cube) You're looking at something and the thing doesn't change, but the aspect by which you're seeing it changes. It flips. And what's salient? What's foreground and background? But this isn't just a shift of aspect, that's why I'm creating this neologism. Right? It's an aspect identity shift.

Fig. 6

What does it mean? You come to see the no-thingness of God. You come to experience it as the inexhaustible creation of meaning. It is an inexhaustible fount of meaning cultivation. It is the ground of meaning intelligibility, the relationship between them, et cetera, for Tillich. Nishitani thinks the same thing can be found within Buddhism. That when we deeply realize the no-thingness of shunyata, when we participate it, when we identify with it, we gain the competence, the ability to aspect shift the nothingness of meaninglessness so that we come to see it instead as pointing to its ground, which is an inexhaustible source of meaning cultivation that cannot be drained dry by our despair.

There is a fecundity at the level of fundamental framing and the way it's coupled to being that cannot be drained dry by despair. When we stop trying to push away the nothingness, but have instead an imaginal relationship to it and move through it anagogically in an imaginal fashion with the nothingness of God, then we overcome meaninglessness. We overcome meaninglessness.

Nietzsche bumped up against this, right? He got close to it. If you stare long enough into the abyss, it begins to stare long enough into you. (Text overlay appears saying, 'John means "If you stare long enough into the abyss it begins to stare back into you."'). But you know what Nietzsche didn't do. He didn't stare long enough. He didn't look deeply enough. That's Nishitani's critique of Nietzschean nihilism.

This fundamental aspects shift in which the nothingness of despair is transformed into the revelation of no-thingness as inexhaustible being meaning. This takes—and Tillich talks about the mystical tradition. There's a term from Gregory of Nyssa (writes Gregory of Nyssa) in the Eastern Orthodox Neoplatonic tradition. And you see it also in John Scotus Eriugena picks it up. This notion of epek-tasis (writes Epek-tasis).

Epek-tasis. Which is such a cool sounding word. It sounds so cool anyways. So this is the idea. So there's a sort of standard, I suppose you might call it a teleological model of sort of salvation, right? Where the point is, you know, I'm moving towards a final destination, the promised land in which I will see God and I will come to rest in the promised land. So, you know, the whole point of a purpose is that it it self-dissolves. When I've achieved my purpose, I've realized my goal, then the pursuit has ended.

But Gregory of Nyssa and Eriugena have this different notion of epek-tasis. So here you're not trying to rest in God. God is not ultimately had even in resting in him. Instead, what the human being is engaging in—now for them, there's a mythos of this continues on after your death, in a life after death. And I'll put that aside. But nevertheless, the notion here of infinite self-transcendence in the infinity of God, right? There is no resting. There is only the constant disclosure of the inexhaustibleness of the ground of being. The transjectivity and the transframing never stopped. They never stopped.

So the method of correlation and the encouragement are therefore, are emphasized as transjective in nature. Tillich explicitly and repeatedly argues that the symbol joins together and grounds—it joins together, but also grounds the subjective and the objective. He talks about how even Nietzsche uses this in the notion of will to power.

Nietzsche in his notion of will to power is trying to use something that has a subjective meaning, will, but also, like, the will to power, power in existence, the way everything is sort of like Spinoza's conatus. Like, pushing itself and maintaining itself in existence. He's trying to get something that bridges between the subjective and the objective.

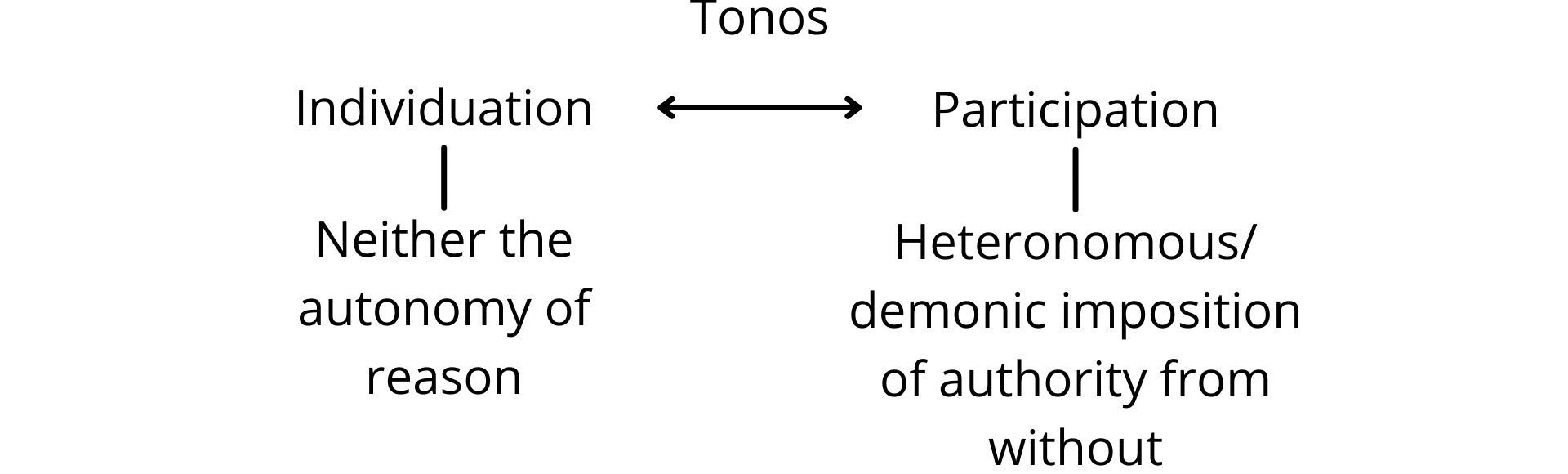

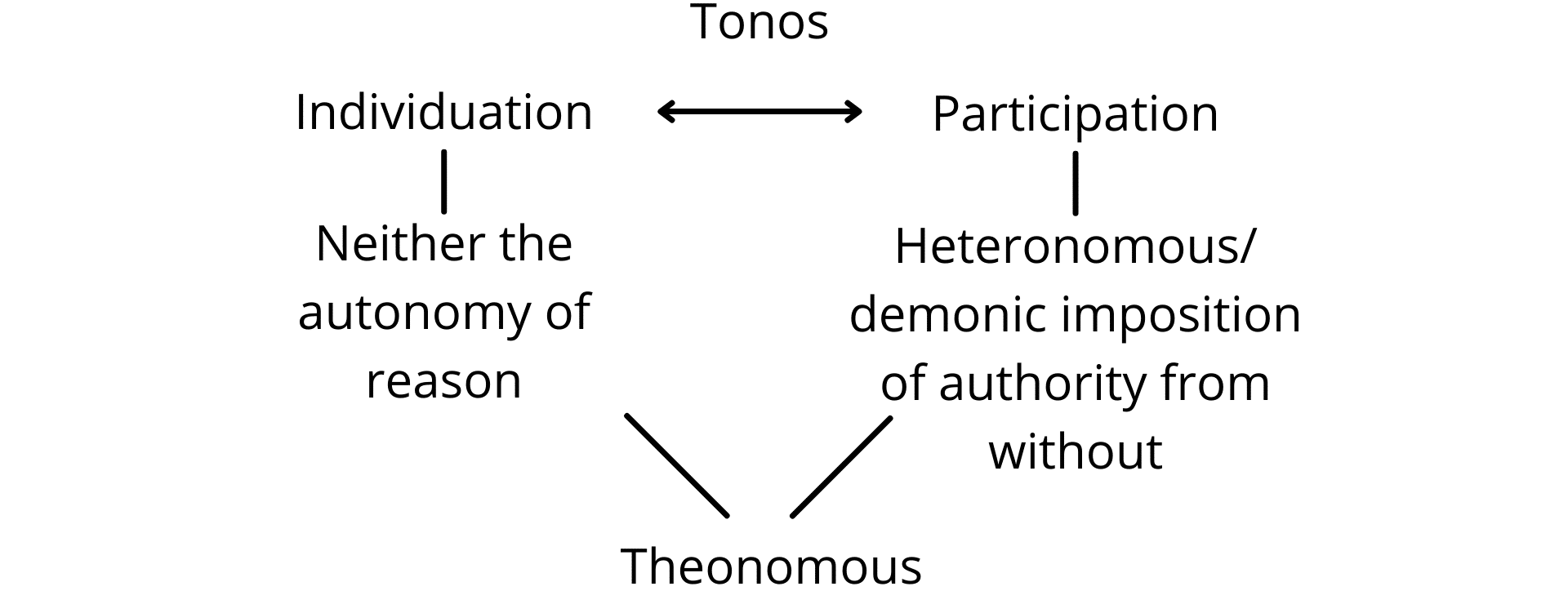

And this is one of the ways in which therefore Tillich is different than Jung. (erases the board). And there's criticism in Tillich of Jung. Also appreciation of Jung. Tillich sees, of course, the process of individuation (Fig. 7a) (writes Individuation), very similar to the way Jung does. And this is perhaps the more subjective side of this symbolic imaginal relationship. But Tillich always, and this is the tonos (writes Tonos above Individuation) again, always puts that into creative tension with participation (draws a double-headed arrow and writes Participation), not just in groups, although he's not excluding that, but this is your participation in being.

Fig. 7a

And he relates that to—and this is really interesting—neither the autonomy of being—sorry, that's wrong, wrong word—autonomy of reason (Fig. 7b) (writes Neither the autonomy of reason below Individuation) emphasized in the enlightenment nor what he calls a heteronomous (writes Heteronomous below Participation) or sometimes he even uses the more religious term, the demonic imposition of authority without—from without (writes Demonic imposition of authority from without).

Fig. 7b

And see how this just so beautifully lines up with the problem of aspiration? Remember it can't be something that just slams you from the outside that you passively receive. It can't be something that you just autonomously make, or you don't actually get genuine self-creation or what I would call self-transcendence.

Tillich sees this overcome in what he calls theonomous (Fig. 7c) (writes Theonomous). Which literally means God-ordered, God-governed, but, of course, God here means the ground of being, the ongoing Epek-tasis of the inexhaustible, the affordance of ongoing transframing.

Fig. 7c

So, what we see here is transjectivity, the sacred second self. We see the anagogic ascent joining reason and revelation together, and the fundamental aspect shift, the deep criticism of fundamentalism and literalism. And there is, of course, therefore, something that is deeply about gnosis. And the connection to gnosticism and the transgression of theory of theism is explicit in Tillich.

Tillich talks about this whole process, and this is why I qualified so much the use of the word theonomous. He qualifies this whole process as the process in which we are responding deeply to the meaning crisis. He calls this as a realization of the God beyond the God of theism. The God beyond the God of theism, which is a deeply transgressive statement.

It's very Gnostic in the sense of seeing God as that, which is the demiurge entrapping us within existential entrapment. The existential entrapment of the meaning crisis. This whole process is so transjective and so transformative in nature and it is so deeply resistant to literalism, fundamentalism, and idolatry that it is going to take us to the God beyond the God of theism.

Non-Theism Of Tillich

This is the non-theism of Tillich (writes Non-theism). Non-theism is a position that tries to transcend theism and atheism. Many people are talking about it now. There's related ideas like anatheism (writes Anatheism), which is sort of the kind of theism that you get after going through atheisms. I think this is a better way of talking about it non-theism. Non-theism is the correct and appropriate way, as I've already mentioned, of talking about religions like Buddhism and Taoism. Non-theism is the rejection of the presuppositions that are shared by both theism and atheism. I will go into this in much greater detail in another series.

Let me just give you—and this is not an exhaustive list. It is just a preliminary list, but nevertheless, I think a good starting point. What are four shared presupposition between the classical theist and the atheist?

Number one, God is the Supreme being. The theist accepts that. Gives a yes to that. And the atheist gives a no to it, but they both accept that proposition as the one they are debating about. The non-theist rejects that.

Number two, God is accessed primarily or even solely through belief. The theist and the atheist agree to this. They just disagree about whether or not there's really any access to be found. The non-theist rejects both of these.

Number three, theology or anti-theology, which is what atheism often engages in. Although I'm not equating atheism to anti-theology. But theology and anti-theology do not require transformative anagoge. All you need to do is have possession of the propositions and be able to infer the correct implications. Thereby losing everything that we've been talking about in these last four episodes. The theist and the atheist agree with that proposition, the non theist rejects it.

Number four, sacredness is personal or impersonal. The theist and the atheist disagree about which one of those to pick. The theist says it's personal. The atheist says it's impersonal. I agree that trying to say that the atheist has nothing that functions like sacredness in their life—this just does not sit with their performative existence. Where—but I do agree when the atheist says that they do not share the theist notion of sacredness as something fundamentally personal. The non-theist rejects that. The non-theist rejects that sacredness is personal or impersonal. Rather because the non-theist rejects the Cartesian grammar that drives it. The non-theist argues that sacredness is transjective participatory. It is aspirational. This is what Tillich was going on about.

My main criticism of Tillich is, although in one way, he's way more practical than Heidegger. He's giving us guidance on how to live, how to cultivate courage and faith. He does not offer practices of transformation. See, Jung actually created a practice, intra-psychic though it might be, he created a practice for enacting and cultivating the imaginal. He created active imagination, which is not just to, in an imaginary sense, call up images. It's not just to conceptually think about things it's to allow images to self-organize in an autopoietic fashion, such that the depths of the psyche are revealed so that the self and the ego can talk to each other. Jung creates a practice of active imagination. He creates a practice of dream interpretation, and that is sadly missing Tillich. Tillich is better than Heidegger. I would argue. In that Tillich gives us a way to live, courage and faith deeply reinterpret it, but he does not give us the processes that Jung gives us.

Owen Barfield

This notion of deep symbolic participation that is translated into practices, I think goes to the heart of Owen Barfield's work. So Barfield is one of the inklings. He is part of the ongoing discussion and fellowship between Tolkien and C.S. Lewis of course, Barfield, Charles Williams. Those are the core four, and then a bunch of other people.

I would recommend three books to try and get a better sense of Barfield. Lost Knowledge of the Imagination by Lachman, which I've already recommended to you. The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings—and there's that word inkling again. The Literary Lives of the Inklings by Philip Zaleski and Carol Zaleski. There's the anyways, that's a very good book. And then the book I would most heartily recommend, it's a book that I'm finding brilliant. It's the book, Owen Barfield: Philosophy, Poetry, and Theology by (writes Di Fuccia)—all of this will come up, of course, on the panels.

So a couple of things. Barfield is definitely influenced by Gnosticism. Gnosticism. He's influenced by Rudolf Steiner. And I won't go into it. You can read the book in depth. Steiner has like—I'll either say too little or too much about Steiner. It's a mystery to many people, myself included, why Barfield was so taken with Steiner and thought so highly of him. But if you reinterpret Steiner as basically a modern Gnostic, who's generating a gnostic mythology, the two worlds and the divine spark and all this kind of stuff, then you understand perhaps why Barfield was so enamored with Steiner. I think Steiner was the vehicle whereby Gnosticism comes into Barfield's thinking.

So Barfield is therefore influenced by gnosis. He's influenced by Neoplatonism through Coleridge, the Romantic poet, who also engages in some important philosophy. Di Fuccia makes very clear. This is one of the most profound parts of the book, the deep indebtedness that Coleridge had to the early Romantics or the post-Kantians people that followed Kant and go on a different path from the later Romantics and Hegel. So a prototypical figure here from these early Romantics or post-Kantians is somebody like Schlegel and what these early Romantics emphasized is they emphasized the infinity. (erases the board) The infinity of reality (writes In-finity)

The Infinity Of Reality

This is really interesting. I find it so. When I'm trying to get the non-finiteness, the lack of being bound, being fully frameable, rather than just being uncountable, although I'm alluding, of course, again, to combinatorial explosion. So they emphasize the infinity of reality. And this term is used by them and by Di Fuccia in his examination of Owen Barfield. This is the inexhaustibleness, the inexhaustible moreness. And the idea is that the inexhaustible moreness is that which continually draws us, constantly draws us and affords us into self-transcendence, that inexhaustible moreness.

So Schlegel had a way of putting this. The finite longing for the infinite. The finite longing for the infinite. It is this eduction (Fig. 8) (writes Eduction)—I'm using this word to draw out, which, of course, became our word education (writes Education below Eduction), which if we think of education aspirationally is fine. The way Callard does. It is this eduction that discloses or reveals the sacredness.

Fig. 8

So our transjectivity, our finite, [-] our epek-static (writes Epek static) trajectory are finite—are always finite, are always framed, longing for the transframing that discloses, but never completely discloses the combinatorially explosive inexhaustible moreness of reality, and simultaneously discloses the ongoing capacity of relevance realization to adapt to that in a coupled manner.

We experience and we participate. I'm using this as a transitive verb. We experience and participate this in creativity, not creativity, just in the sense of making, but the creativity that you experienced in the flow state. See how this is different from the later Romantics? This is not to find the contact in realness in some irrational locus in the psyche or in Hegel as the dialectic of a system, a propositional system. But instead it's to find sacredness in the flow of self-transcendence within creativity. And this is what is meant by poesis (writes Poesis). What we translate as poetry.

Poesis As Ekstasis In Creativity

Barfield picks up on this poesis as ekstasis in creativity, the way we stand beyond ourselves in creativity. And he's very clear about how this is a transformative experience. There's a felt change in consciousness. The self after is both continuous and discontinuous from the self before the transformative experience. All that stuff we've been talking about with the sacred second self and aspiration.

There's an ekstasis within the creative—there's an ekstasis in creativity. There's an ekstasis in creativity found within poetry and the poetical aspects of everyday language that can reawaken us to this kind of connectedness. To the inexhaustibleness. A connectedness that experiences as sacredness.

So Barfield looks at words, the etymology, the history of words. And I touched on this briefly earlier when I was talking about symbols and I made some, sort of, criticisms of Barfield, which I noted at the time were preliminary and promissory. And I promised to come back to them in more depth as a way of trying to both defend my criticism, but also to defend a deeper reading of Barfield.

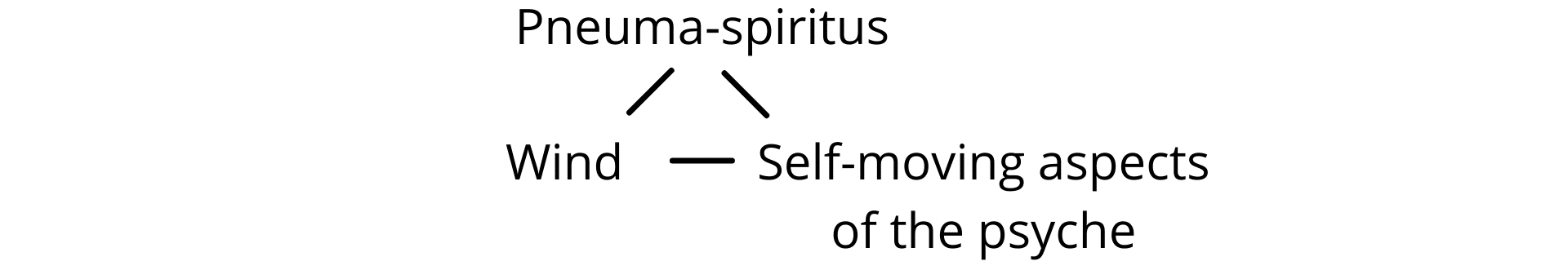

So you remember (erases the board), the idea here is we have a word like pneuma (writes Pneuma), the Greek for spiritus (writes Spiritus beside Pneuma). And Barfield knows if you go—and for us—so for the Greeks, for the Latins, for the Romans, for spiritus, it can mean both wind (Fig. 9) (writes Wind) or what we now think of the word spirit sort of the self-moving aspects of the psyche (writes Self-moving aspects of the psyche). And we divide it into spirit is this (indicates Fig. 9). We really can't see it that way, but there's a division here and for Barfield, this division replicates this sort of Cartesian division between the objective world of like wind and the subjective world of what's going on in the psyche in itself movement or self-contact. But what Barfield says is when you go back, there isn't this (draws a line between Wind and Self-moving aspects of the psyche). These terms are used and they're treated as if they have a kind of identity, what I would argue as a non-logical identity, [-] they interpenetrate, they inter-afford each other, these meanings that we see as so antithetical, so disjunctive with respect to each other.

Fig. 9

For Barfield, people who used the word that way were engaged in a form of participation. This is a way of being before the division, before the Cartesian disjunction, I would argue that what Barfield is pointing to is that these people had a more transjective anagogic resonance with reality so that the wind is imaginal for them in that it discloses the self-moving aspects of reality and themselves in a highly resonant fashion.

The reason I want to say that is because I'm not quite sure about his evolutionary hypothesis. I pointed to the work of Lakoff and Johnson, that show we, unlike the people of the ancient path, we use language in this fashion. A way that is pervasive through all of our cognition and speech. Words have these dual meanings and inner and outer meaning.

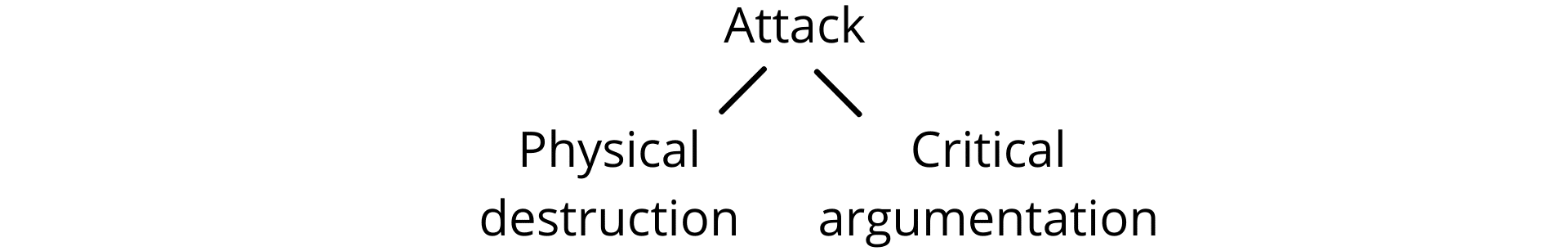

I pointed to work that I've published on and work that they published on (erases the board). How we use the word attack (Fig. 10) (writes Attack). There's many examples. This is only one. That's the point. There's many, many of these examples. We use the word attack and we mean physical destruction (writes Physical distraction below Attack). Like I attack the castle, at least the intent to physically destroy it. But we also mean critical argumentation (writes Critical argumentation). Like he attacked that point that I just made and we don't feel they're not ideologically identical, but we don't feel them as, you know, radically disjunctive from each other.

Fig. 10

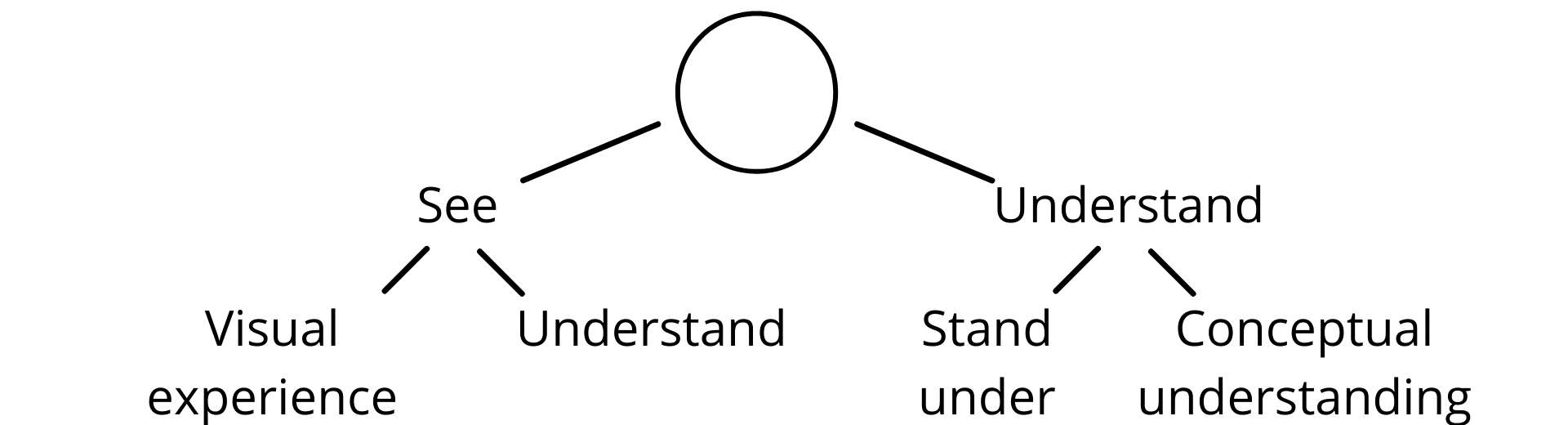

Notice we do it with this (writes See)—sorry (erases See). Yes. I want to do it that way. There's something here (Fig. 11) (draws a circle and draws a line below) and we'll use the word see (writes See). And we can use that to mean either visual experience (writes Visual experience below See) or we can use see to mean to understand (writes Understand below See). And then that converges back, we can use understand or originally unterstand, but we changed it to understand (writes Understand below the circle), and that can mean to stand under (writes Stand under below Understand), but it can also mean conceptual understanding (writes Conceptual understanding). And so there's a weird synonymy between understand and see. I'm trying to point out to you how complex this is.

Fig. 11

Now what's interesting about Lakoff and Johnson is they don't claim this as an evolutionary thing, pointing to ancient ways of being conscious. This is something pervasive in our cognition and our culture right now. And it doesn't point to the evolution across generations. It points to psychological development within individuals. Psychological development within individuals.

According to Lakoff and Johnson, we start out in sensory motor seeing and then that gets taken up into this conceptual sense of seeing. We start with a sensory motor way of understanding that gets taken up. We start as a sensory motor way of attacking. And that gets taken up. It's a psychological process of development and it is ongoing right now and it is pervasive. There might be something sort of fundamentally wrong therefore with Barfield's evolutionary analysis.

Now Vervaeke and Kennedy argue that the psychological development is deeper than as being represented by Lakoff and Johnson. We argued that the model is too simplistic. As I mentioned, we argued that there should be a top-down aspect to this psychological development, not just bottom-up.

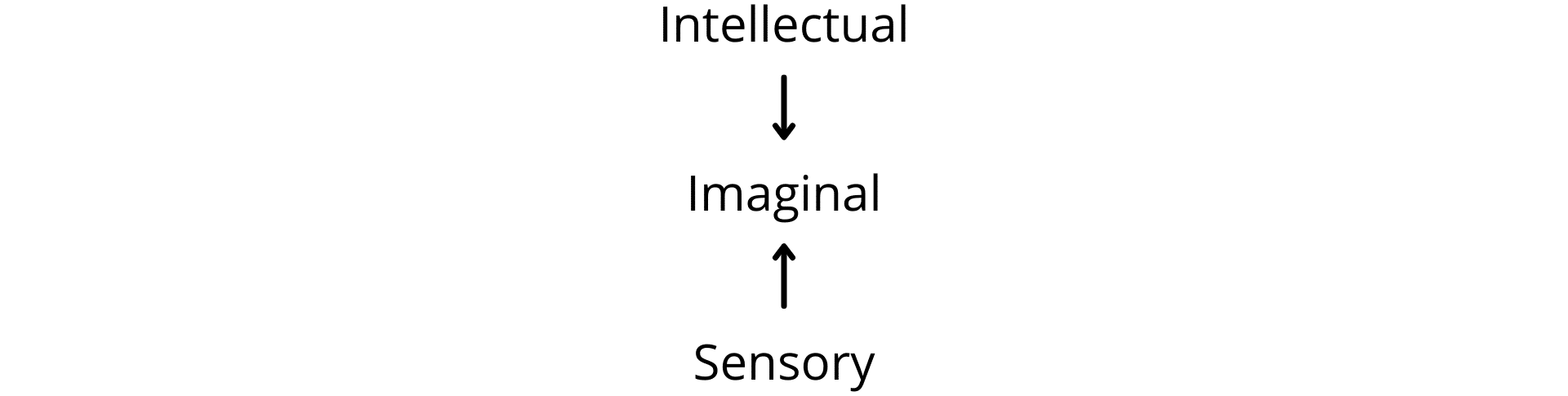

So there's a sense in which we agree with Lakoff and Johnson that there's stuff coming up from the sensory (Fig. 12) (writes Sensory and draws an upward arrow above it), but we think—and here's the influence of Corbin, right? Especially on me. I don't know if there's an influence on John Kennedy, but definitely on me. Here's the abstract intellectual (writes Intellectual above Sensory and draws a downward arrow below) and here's the concrete sensory, and then they meet together in the imaginal (writes Imaginal between Intellectual and Sensory). That when I say, I see what you're saying, this is an imaginal way that's getting a bottom-up from seeing as a sensory motor thing, and then bringing into imaginal expression this abstract not yet speakable sense of understanding.

Fig. 12

That helps to explain why these two (indicates See and Understand) very different sensory motor things, verbal experience, standing under—or a totally different one: grasping—or yet another one: getting. Why do all of these converge? Because there is something like an intellectual form that they converge upon, but it is also expressed, developed through these different imaginal renderings that connect back to concrete instances of the sensory motor.

I argued that we can link that to Michael Anderson's notion of their massive redeployment hypothesis. The circuit we use, cognitive exaptation. I went through this idea of how the symbolic—now you can understand that's the imaginal, is this process of re-exaptation (writes Re-exaptation). How I can invoke balance.

I can evoke balance to talk about justice. And then I have the image, not an imaginary, the imaginal statue of lady justice, as a way of using, re-exapting the physical balance machinery and using that machinery to give a structural functional organization to this hard to articulate ineffable sense of justice. Recycling that whole process and inducing new functions. It's an enacted metaphor. It's an enacted symbol. This is poiesis, I think in its deepest sense.

This helps to explain the translucency of the symbol, why we can see through it. See it and see through it. I can look at it as physical balance, but I can see through it into justice. And justice and balance are not logically identical, but they're not separate from each other. It also explains our temptation to literalism and idolatry. We can forget, we can forget justice and focus just on having balance. We can lose the iconic seeing through and only look at the concrete.

Final Participation

Now back to Barfield's evolutionary schema, he talks about that we had original participation and then there's the division, which is the meaning crisis. And he's really explicit about the meaning crisis. Read the opening essay in The Rediscovery of Meaning. He's really clear about that. And then we have the two worlds of mythology and everything is being broken up. The inner and the outer are being separated. The subjective, the objective, blah, blah, blah. You know, all of this, the idea is what we need to do is to move to what he calls final participation as a response to the meaning crisis.

Final participation is a recovery of participation integrated within the gains of the rational sciences. Now he says that and that's explicitly and importantly what he means. And I take him at his word. Part of what that means, and this is what he emphasizes, is the recovery of the perspectival and the participatory. And I think that is deeply right and deeply consonant, but here's where I'm critical of Barfield.

But I think it also means, and this is where Barfield does not do, I think, good work. It also means a science of meaning cultivation. How does that participatory and perspectival participation fit into our scientific processes, our scientific way of being? If you're going to integrate in final participation, participation with the scientific, rational mind, both sides have to be involved in this marriage, or it will fail. That, of course, is what I've tried to do with relevance realization theory, and then put it into discourse with spirituality, symbolism, sacredness, and these great prophets of the meaning crisis.

Now here's more of a criticism of Barfield's followers. I think there needs to be more understanding of how much Barfield is indebted to Coleridge and Schlegel and understanding sacredness as a poiesis participation of the inexhaustible within transformative creativity. You can't simply import Barfield into classical theism and say, Oh, he's just talking about the things we've always been talking about. How is that going to bring about final participation? That is not fair to Barfield's argument or his ideas.

This leads to the point that Di Fuccia argues that this is what makes Barfield different to Heidegger. Heidegger, as we saw, took from Eckhart, this notion of relating to this, letting the rose be. And he takes up this notion from Eckhart. Gelassenheit (writes Gelassenheit) . John Caputo talks a lot about this, the letting be. And he tends to emphasize a deep—so you can see what Heidegger's doing. He's trying to respond, but like Nietzsche, he's overcompensating Descartes' notion of the complete activity of mind. So Heidegger responds by a complete passivity, Gelassenheit. Letting be, letting be. It's a deep passivity. It's so bloody Lutheran.

And there's something deeply right about that aspect of Eckhart, but Heidegger forgets the other important term in Eckhart, Durchbrock, Durchbrock. Breakthrough. Breakthrough (writes Breakthrough). You know what breakthrough is all about? It's about attentional scaling (draws an arrow pointing to Break), breaking the inappropriate frame (draws an arrow pointing to Through) moving through and making the new frame.

Durchbrock is just as important as gelassenheit . And this is something Barfield picks up on. That his notion of creativity as participatory is not to be just passively receptive. Of course, it's not what Heidegger criticizes either. The Cartesian technological imposition of our will on the world. That's not what's meant by poiesis either.

Poiesis is synergistic. God—because I think Barfield is ultimately non-theistic in some very important ways—God plays the leading role, but we contribute. And this was the original Hebrew insight of the da'at. We're not just passive recipients of history, nor are we it's complete authors. We participate history. We participate in history and we are synergistically working with God in its making.

Is Barfield a non-theist? I don't know. I can't make that argument as clearly as I can make it for Heidegger, for Jung, for Corbin, for Tillich. I suspect though, if Barfield were to talk to these other prophets of the meaning crisis, he would also be led into a kind of non-theism. That is clearly the case with people like Schlegel, who so deeply influenced him.

What have I tried to show you? I've tried to show you that the language—not the language, the vocabulary, the grammar, the framework of relevance realization and how it can be developed to talk about spirituality and sacredness can be put into deep dialogue with Heidegger. Deep dialogue with Corbin. Deep dialogue, with Jung. Deep dialogue, with Tillich. Deep dialogue with Barfield. And also afford deep dialogue, critical but creative dialogue, between them and afford a potential synoptic integration. All of this is what I've meant by and what I mean by awakening from the meaning crisis.

Thank you so very much for this long journey, we have traveled together. I've often taxed your attention, your patience, your understanding, your good spirits. I thank you for the ongoing support and appreciation and encouragement many of you have given me. And I look forward to an ongoing dialogue in the next series that I will create. Thank you very much. And I want to thank deeply the crew, constant here. My brothers in this project who continually afforded it and made it possible to be presented to you at the time exemplary level of excellent quality.

Thank you very much one and all.

- END -

Episode 50 Notes

To keep this site running, we are an Amazon Associate where we earn from qualifying purchases

Paul Tillich

Paul Johannes Tillich was a German-American Christian existentialist philosopher and Lutheran Protestant theologian who is widely regarded as one of the most influential theologians of the twentieth century.

Book Mentioned: The Courage To Be – Buy Here

Book Mentioned: Morality & Beyond - Buy Here

John Dourley

John P. Dourley was a Jungians analyst, a professor of religious studies, and a Catholic priest. He taught for many years at Carleton University in Ottawa, his doctorate being from Fordham University.

Book Mentioned: The Psyche as Sacrament – Buy Here

Book Mentioned: Paul Tillich, Carl Jung and the Recovery of Religion – Buy Here

Book Mentioned: A Strategy for a Loss of Faith - Buy Here

Da'at

In the branch of Jewish mysticism known as Kabbalah, Daʻat is the location (the mystical state) where all ten sefirot in the Tree of Life are united as one.

Dasein

Dasein is a German word that means "being there" or "presence", and is often translated into English with the word "existence".

Aletheia

Aletheia is truth or disclosure in philosophy.

Sophrosyne

Sophrosyne is an ancient Greek concept of an ideal of excellence of character and soundness of mind, which when combined in one well-balanced individual leads to other qualities, such as temperance, moderation, prudence, purity, decorum, and self-control.

Keiji Nishitani

Keiji Nishitani was a Japanese university professor, scholar, and Kyoto School philosopher. He was a disciple of Kitarō Nishida.

Book Mentioned: Religion and Nothingness – Buy Here

Necker cube

The Necker cube is an optical illusion that was first published as a Rhomboid in 1832 by Swiss crystallographer Louis Albert Necker.

Śūnyatā

Śūnyatā – pronounced in English as /ʃuːnˈjɑː.tɑː/ (shoon-ya-ta), translated most often as emptiness, vacuity, and sometimes voidness – is a Buddhist concept which has multiple meanings depending on its doctrinal context.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a German philosopher, cultural critic, composer, poet, writer, and philologist whose work has exerted a profound influence on modern intellectual history.

Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen, was bishop of Nyssa from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death.

John Scotus Eriugena

John Scotus Eriugena or Johannes Scotus Erigena or John the Scot was an Irish Catholic Neoplatonist philosopher, theologian and poet in the Middle Ages.

Will to power

The will to power is a prominent concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematically defined in Nietzsche's work, leaving its interpretation open to debate.

Spinoza (Other names: Benedictus de Spinoza)

Spinoza, Baruch, Dutch philosopher, of Portuguese-Jewish descent; also called Benedict de Spinoza. Spinoza espoused a pantheistic system, seeing ‘God or nature’ as a single infinite substance, with mind and matter being two incommensurable ways of conceiving the one reality.

Richard Kearney

Richard Kearney is an Irish philosopher and public intellectual specializing in contemporary continental philosophy. He is the Charles Seelig Professor in Philosophy at Boston College and has taught at University College Dublin, the Sorbonne, the University of Nice, and the Australian Catholic University.

Book Mentioned: Anatheism: Returning To God After God - Buy Here

Owen Barfield

Arthur Owen Barfield was a British philosopher, author, poet, critic, and member of the Inklings.

Book Mentioned: The Rediscovery of Meaning, and Other Essays - Buy Here

Gary Lachman

Gary Joseph Lachman, also known as Gary Valentine, is an American writer and musician.

Book Mentioned: Lost Knowledge of the Imagination - Buy Here

Philip Zaleski

Philip Zaleski is the author and editor of several books on religion and spirituality, including The Recollected Heart, The Benedictines of Petersham, and Gifts of the Spirit.

Book Mentioned: The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings - Buy Here

Michael Vincent Di Fuccia

Book Mentioned: Owen Barfield: Philosophy, Poetry, and Theology - Buy Here

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was a German philosopher and is considered one of the most important figures in German idealism.

Friedrich Schlegel

Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel was a German poet, literary critic, philosopher, philologist, and Indologist. With his older brother, August Wilhelm Schlegel, he was one of the main figures of Jena Romanticism.

George Lakoff

George Philip Lakoff is an American cognitive linguist and philosopher, best known for his thesis that people's lives are significantly influenced by the conceptual metaphors they use to explain complex phenomena.

Mark Johnson

Mark L. Johnson is Knight Professor of Liberal Arts and Sciences in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Oregon. He is known for contributions to embodied philosophy, cognitive science and cognitive linguistics, some of which he has coauthored with George Lakoff such as Metaphors We Live By.

John Caputo

John David Caputo is an American philosopher who is the Thomas J. Watson Professor of Religion Emeritus at Syracuse University and the David R. Cook Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Villanova University.

Book Mentioned: The Mystical Element In Heidegger’s Thought - Buy Here

Gelassenheit

Often translated as "releasement," Heidegger's concept of Gelassenheit has been explained as "the spirit of disponibilité [availability] before What-Is which permits us simply to let things be in whatever may be their uncertainty and their mystery."

Meister Eckhart

Eckhart von Hochheim OP, commonly known as Meister Eckhart or Eckehart, was a German theologian, philosopher and mystic, born near Gotha in the Landgraviate of Thuringia (now central Germany) in the Holy Roman Empire.

Poiesis

In philosophy, poiesis is "the activity in which a person brings something into being that did not exist before.

Other helpful resources about this episode:

Notes on Bevry

Additional Notes on Bevry