Ep. 39 - Awakening from the Meaning Crisis - The Religion of No Religion

(Sectioning and transcripts made by MeaningCrisis.co)

A Kind Donation

Transcript

Welcome back to Awakening from the Meaning Crisis.

So last time, I was making a proposal to you of how we could address the perennial problems. And I gave you a systematic set of things that could be cultivated in an integrated fashion for addressing perennial problems. And then we saw how that interacts with our attempts to ameliorate and alleviate the perennial problems, interact with the historical forces, and that we get the fundamental undermining of meaning in life and that problem set by Wolf. And then I proposed to you that there was a response to that in terms of the notion of agape and then I moved into the direct addressing of the historical forces looking about for recovery of something like what the three orders did for us.

And then I propose to you that if we took a look at 4E cognitive science, third generation cog sci, and, in particular, some of the insights afforded by 4E cognitive science, third generation cog sci and that were pointed out by Varela in his article. We can see ways in which we can get a worldview that strongly situates our meaning making processes within it, legitimates it. We talked about how we can recover something like the nomological order and the normative order and how, perhaps, we can move to something post-narrative, an open-ended optimization that is seeking for a depth of realization rather than a historical combination. And I proposed to you bringing with it the notion that Goodenough bringing with that whole project of responding to the historical forces and trying to bring with it a new notion from Goodenough's work on transcendence into rather than transcendence above or beyond and how that is resonant and consonant with the picture that we've been working on together.

Couple things remain that are central. One, of course, is to give an account, a cognitive scientific account, of wisdom because of the wisdom framing that is needed for both the cultivation of the responses to the meaning crisis and the use of, interpretation of, grasping the significance of the cognitive scientific framework. So we need to develop an account of wisdom together. And I also said, we need to talk about this notion of getting something that's a religion that's not a religion. And what might that look like?

So I want to address the second point first because I have less to say about it, not because it's not important. I've less to say about it because it's very tentative. And I want to try and talk about it in, ultimately, a suggestive fashion. I'm not trying to found a movement or anything ridiculous or pretentious like that. There are many people though, who are writing books about this idea. I recommend to you James Carse's book, The Religious Case Against Belief, which I've already recommended. There's Unger's book on future religion. There's a book like a Religion for Atheists in which people are, I think—and I mean this in a serious sense, but they're trying to play with what this might look like: a religion that's not a religion and how can it help us to address it? Even people like Richard Dawkins are trying to propose, you know, that we should get a cultivated ability, ultimately poetic ability, to engender wonder and awe that is consonant with the scientific worldview. So a lot of people are trying to get some conceptual vocabulary and theoretical grammar going for this so I do not see myself as offering anything definitive or authoritative, but on the basis of what we have done together, I'd like to try and offer some suggestions of what this would look like.

Remember, why are we setting this problem while we, we, for many of us... And the group that I self identify as the Nones, having no religion, nevertheless, a large majority of those people are still spiritually hungry in important ways. Returning to organized religion is not a viable option. And part of that has to do with a lot of the history that we've traced out and pursuing pseudoreligious political ideologies and utopic visions is also not viable precisely because of the trauma of the 20th century and parts of the 21st century and the clash of the pseudoreligious ideologies and the way they drenched the world with blood and torture and horror.

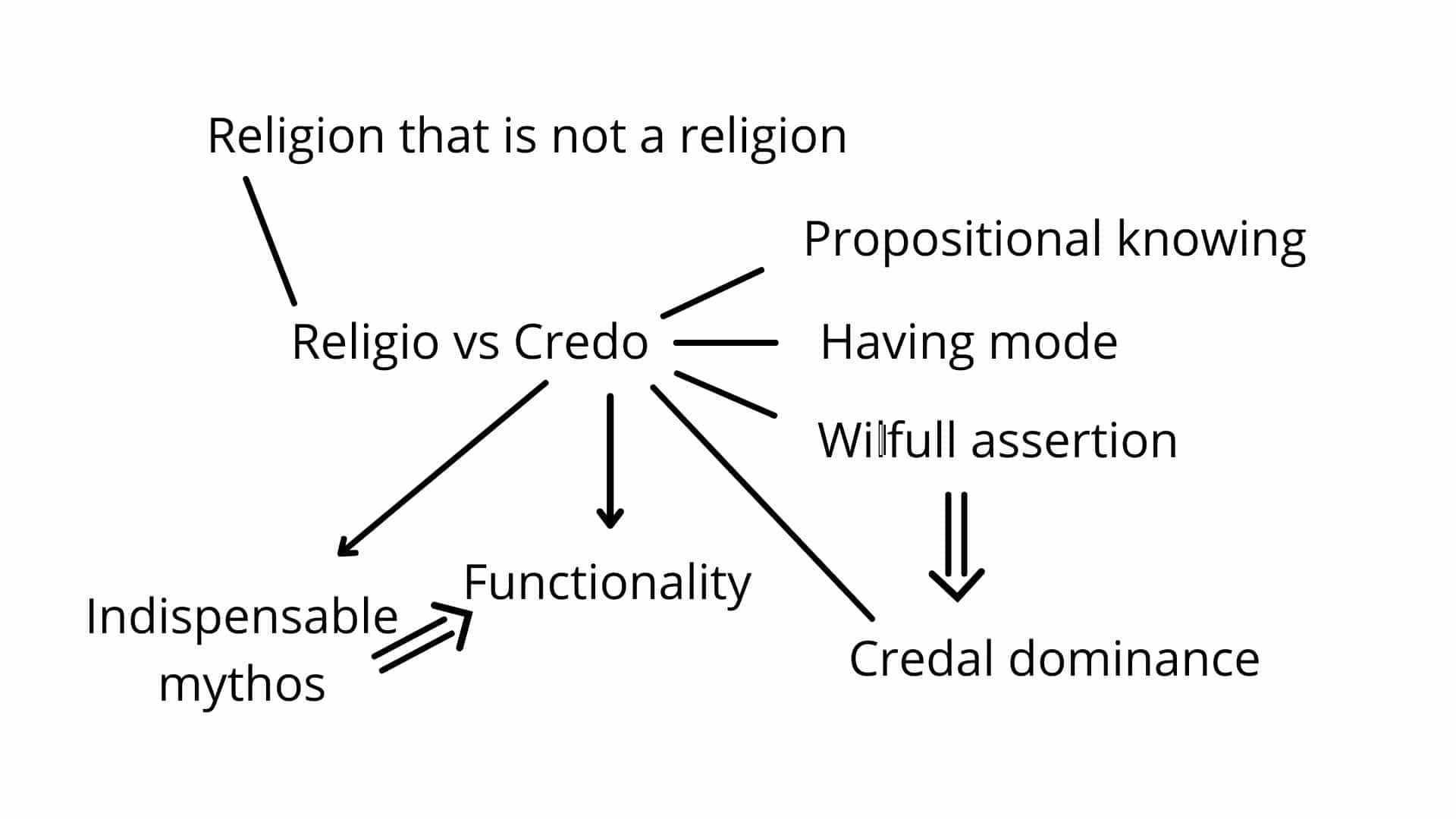

And so I propose to you that nevertheless, we need to do something like what religion used to do. We need a comprehensive set of psychotechnologies that are set within communities of practices that allow for the comprehensive transformations of consciousness, cognition, character, and culture in a way that is analogous to religion —that is what we're looking for. Something that can do all of that, because that is what we need. That kind of transformation is needed today to address what Tomas Björkman calls the meta-crisis of all the various crises that we are facing and that are interacting with each other in what looks to be an increasingly accelerating fashion and having an increasingly deleterious effect on us individually and collectively. So that is part of the problem. And what would it look like: the religion that is not a religion? (writes Religion that is not a religion) Again, as I said, there are many people who are taking a stab at this or trying to get a grip on this. And so I am just seeing myself as contributing to, hopefully helpfully to that dialogue.

Religion vs. Credo

So part of it, I think is, and this is of course, what I've tried to do is to acknowledge the centrality of Religio. (writes Religio below Religion that is not a religion) and that there is an important role for indispensable mythos in the activation, accentuation, acceleration, appreciation of religio. And so I think that is something that should be acknowledged as what we would be looking for. And this brings out an important contrast (writes = beside Religio) I want to discuss (erases equal sign). Sorry, not equal. Religio versus credo (Fig. 1a) (writes Vs. Credo beside Religio). Let us talk about this a little bit and try and get clearer about it, 'cause we have this idea of an open-ended mythos analogous to the transgressive mythology of the Gnostics.

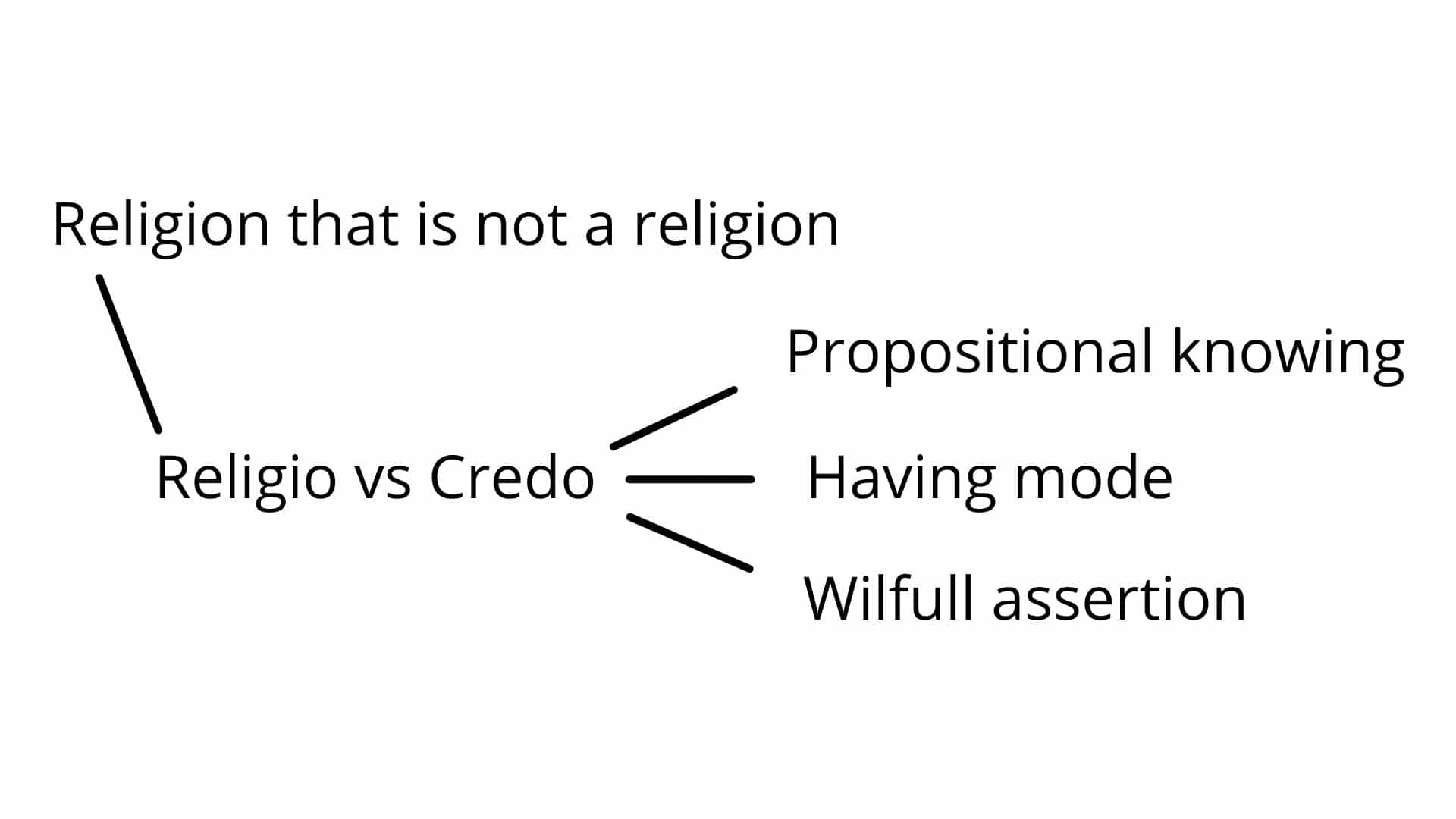

Fig. 1a

So credo, of course, means I believe. And it's the word behind things like the Nicene Creed or the Apostolic Creed. A notion of credo is a notion of, sort of, a paradigmatic set of propositions that state what the essence of a religion is in terms of the truth content that is supposed to be believed. And so what has happened to some degree in various ways—and I tried to show you this (indicates Credo)—as—this (continues to indicate Credo), of course, is linked to propositional knowing. And as propositional knowing (writes Propositional knowing beside Credo) has come into ascendance, right? And as the having mode (writes Having mode below Propositional knowing) has come into ascendance, the having of propositions that are asserted, right. And, of course, willful assertion. (writes Willful Assertion below Having mode). We've seen all of this has come into ascension. This (Credo) has tended to become dominant. So as I've mentioned, we often think about religions or speak of them as if they are belief systems—systems of beliefs. And so you have propositional knowing, you have the having of those propositions and the way you have them is ultimately to assert them in some fashion, usually in a willful fashion (indicates Willful assertion), where I mean that very broadly in the way that we've discussed here, where it is not something that is ultimately derived from reason, but it is something that is being asserted nevertheless.

Fig. 1b

Fig. 1b

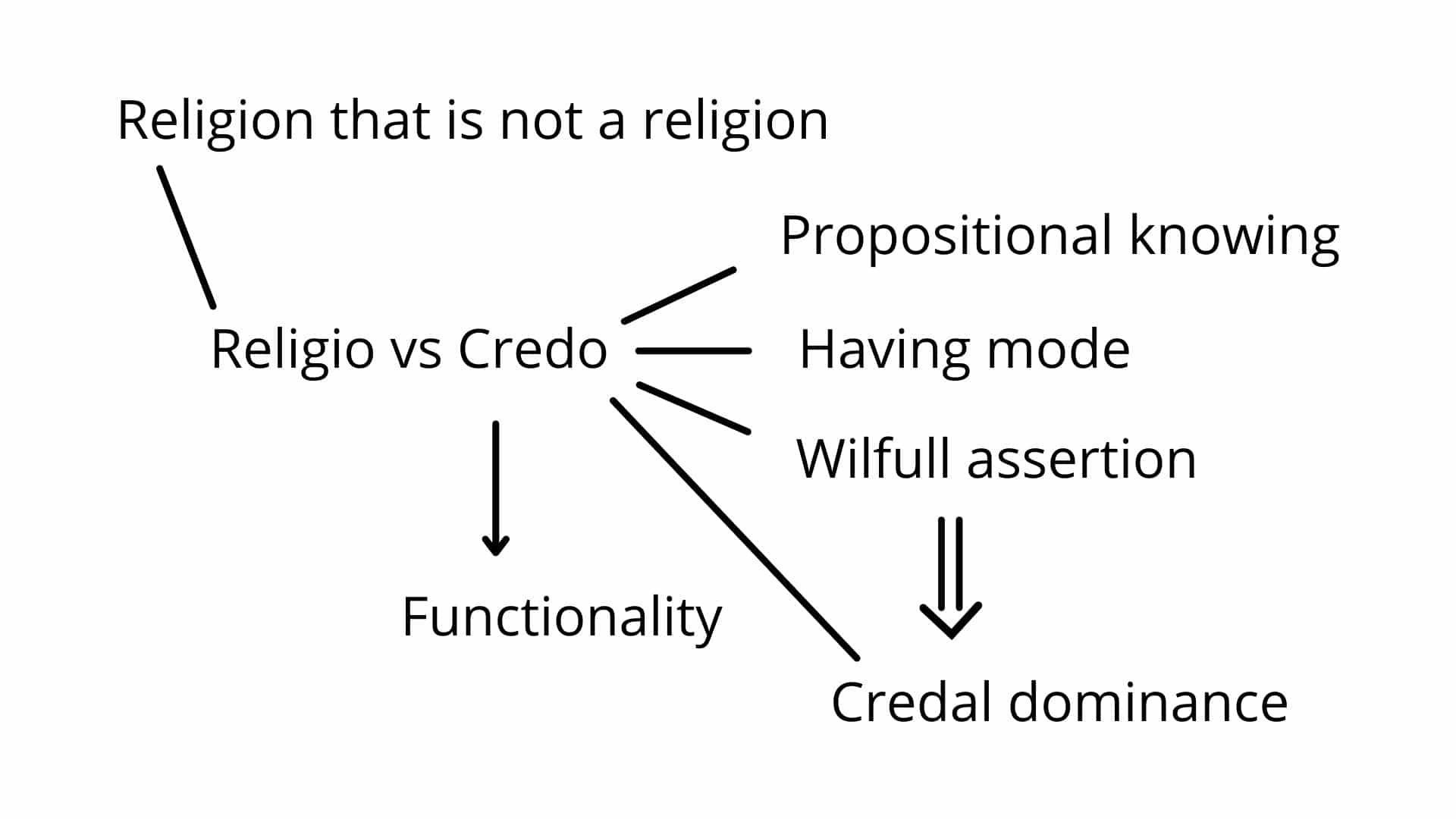

Now, I think there's an important role for credo. And so I want to make a distinction between credo and this credal assertion (indicates Propositional knowing, Having mode, Willful assertion), credo dominance. So let's talk (draws a downward arrow from Willful Assertion and a line from Credo) about this set of things as credal dominance (Fig. 1c) (writes Credal dominance below Willful assertion). (draws an arrow from Credo) But let's talk about perhaps a way of understanding the functionality of this (writes Functionality).

Fig. 1c

Fig. 1c

Now, first of all, I'm, of course, aware of the postmodern critique and I will have a final— towards the final end of the series, I'll come back and talk about postmodernism, but I'm aware of the postmodern critique in that a lot of this is, and that makes sense, given credal dominance (indicates Credo), that this is enmeshed with power, with dominance, with control, with creating sort of purity codes where we have boundaries of identity, of the us and the other, all of that. I think it's a legitimate form of argument and something I take seriously, but I would put that under credal dominance and I would want to try and take out of what remains, what function can we see for people doing this and how might we understand it?

Well, first of all, like I said, we can think of people (draws arrow from Credo) having paradigmatic statements and pictures that this might be a function of indispensability (Fig. 1d) (writes Indispensability mythos below Credo) to them so they can understand it. We can understand it as indispensable mythos. Again, it's highly plausible that there is a mythos for you or for groups of people that is indispensable, given the contextual sensitivity, the dynamic coupling of religio, that there's sets of symbols and stories and celebrations and shows and souvenirs and all the things associated with mythos that are indispensable for getting the kind of sacredness out of religio that people want and need in response to, for example, the perennial problems. So again, this, of course, is part of the philosophical reason—there's also an independent moral reason, but this is part of my philosophical reason why I try to be deeply respectful to religious creeds, precisely because even though I think all of these criticisms, or all the criticisms associated with this, criticisms that I've added to in this series, I think they're all legitimate— I think this (Indispensability mythos) is also a very legitimate thing. Now, of course, the problem is, is to confuse indispensability with metaphysical necessity and to confuse need with authority.

Fig. 1d

Fig. 1d

And we've talked about all of that. What I think we can sync it. This is not only indispensability (indicates Indispensability mythos) that's idiosyncratic to people or the group. We can also talk about an indispensable functionality that might be more universal in nature. And this has to do with the basic idea from all of information processing from what's called signal detection theory (writes Signal detection theory).

Signal Detection Theory

So signal detection theory is a theory that basically argues that we're always facing perennial problems when—and, I mean that to allude to the perennial problems that I've talked about here— whenever we're doing information processing, there's aspects in which the information is there's, and this is no contradiction, there's simultaneously too much information, but there's often inadequate information. Like you're not seeing all of my body right now. So the information is simultaneously overwhelming and partial. The information is often ambiguous. It's unclear if that information is the information you need or you're being misled in some way by information that's similar, but not in the relevant way to the information you're looking for.

So all of these things, point to an important point—an important general conclusion. Now I'm going to have to use two terms here. I'm going to use the word signal (Fig. 2) (writes Signal) and this means information (writes Information beside Signal) I want. Information I want or need (writes I want below Information). And then noise (writes Noise below Signal). Noise does not mean audible distortion. Audible distortion is one kind of it what this means is this means information I do not want (writes Information I do not want beside Noise). It's in some way distracting, right? It's in some way, misleading, et cetera.

Fig. 2

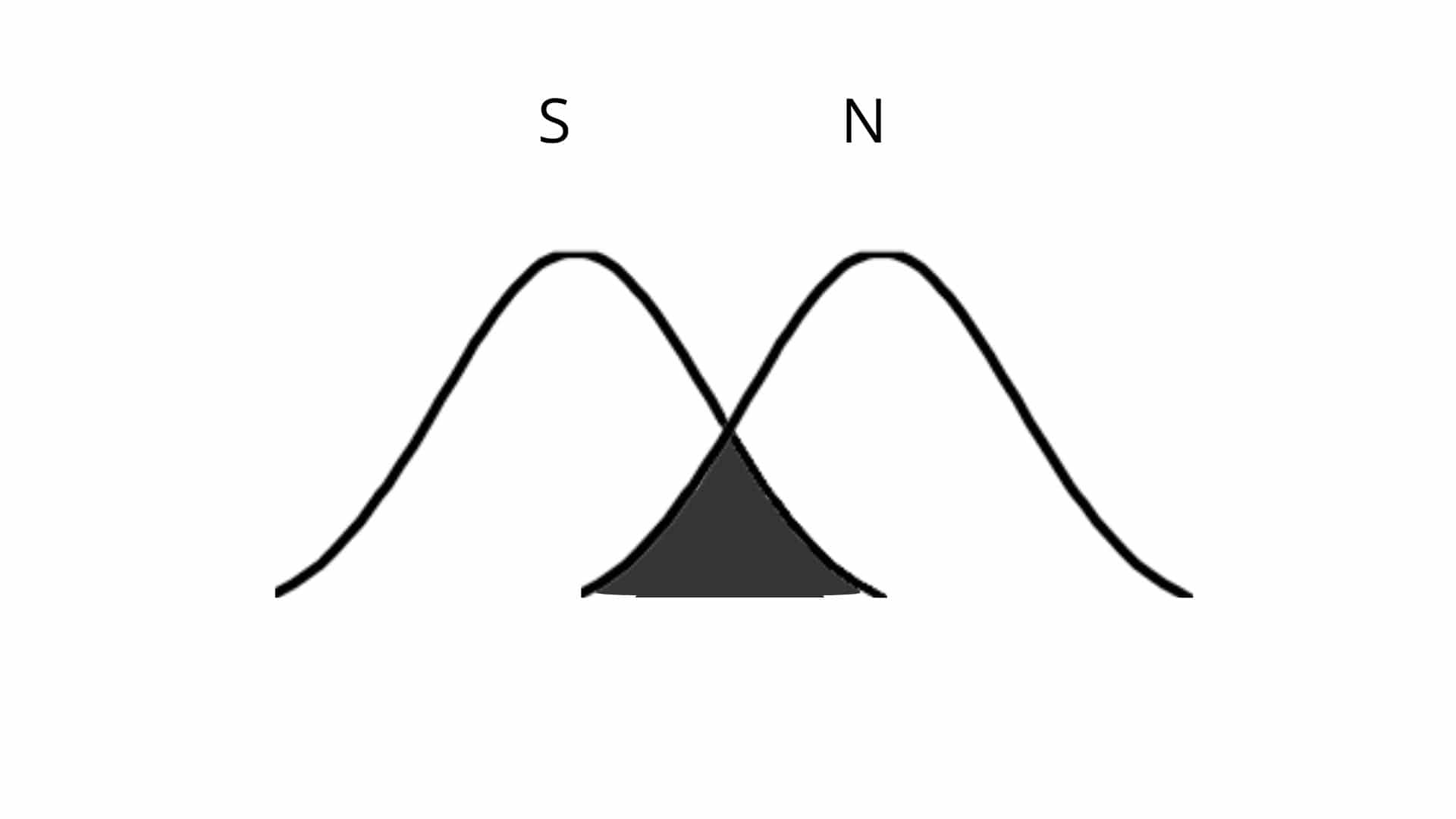

So here's the idea. Here's the population of events (Fig. 3) (draws a bell curve) that constitute signal that you're looking for (writes S above the bell curve). And the idea is there's always a significant overlap with noise (draws another bell curve overlapping the first bell curve and writes N above it). Again, where noise doesn't mean audible distortion. It means any information that you don't want, that it can be confused with—look at—con"fused" (indicates the area where the bell curve overlaps;) with—can be confused with signal.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

So let's take a prototypical example, right? The prototypical example is this: you're a gazelle and you hear a noise in the Bush. Now that could be [an] important signal. It could be information that you want because it's information telling you that a leopard is near or the noise in the Bush could be noise in this technical sense. It could just be the rustling of the leaves caused by the wind. And that is, and this is the important term here: that's irrelevant to you. That's irrelevant to you. That might be a signal for somebody else or something else. But for you as the gazelle, it's irrelevant, see, being signal and noise, of course, is a matter of relevance realization.

So you're, sort of, caught here, right? Because if you're the gazelle, what you're experiencing is this, this zone right here (shades the overlapped area of the bell curve; grey area in Fig. 3), right. This zone of overlap between the signal and the noise. You don't know what it is. Now, what you can say is, well, what I'll do is I'll get more information. And there's a sense in which that helps, but you have to also understand that there's a diminishing return here because any new information that I try to get to resolve this will also suffer from this problem (draws another 2 bell curves that overlaps). And this, of course, goes again towards: you can't ultimately get certainty, et cetera, et cetera. Also the more I regress and try to get signal about my signal, about my signal, about my signal, the more time I'm taking, and often time is an important constraint. So first of all, you can't ever escape this (the overlapping bell curve) problem. And as you try to reduce it, you have to put in a lot of time and effort that can ultimately be too costly for you. So the idea is there's a sense in which every act, even an act of perception is, to some degree, risky, it's a gamble. And this is part again—and we talked about this— Tim Lillicrap, Blake Richards, and I in the paper on relevance realization. This is part again of the issue of trading off between various contingencies.

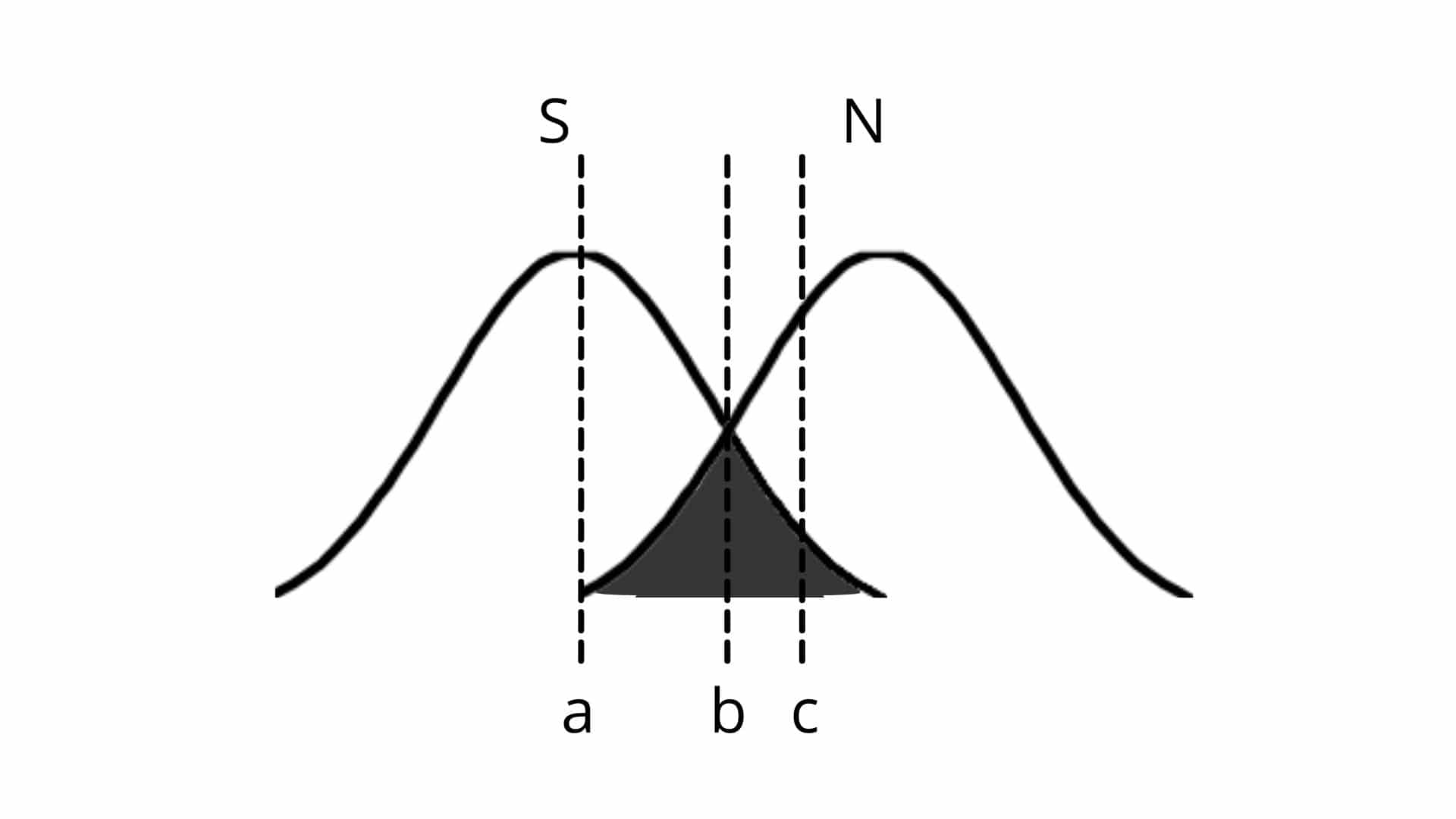

Setting the Criterion

What's the trade off here? Well, the trade off is I have to set the criterion. So the criterion is basically—what I do is I put a dividing line (draws line c in Fig. 4), a decision line. Remember? Decide ultimately means to cut. And I'm going to include everything to the left as signal (indicates the left bell curve) and exclude everything to the right. Now what's the problem with that? Well, the problem with that is I'm now opening myself up to different kinds of errors. So one of the things I can do here is I can—if I set my criterion too high, for example, I will include a lot—I will treat a lot of noise as signal. If I set my criterion way down here—"I don't want to ever be wrong. I'm going to set my criterion really low (erases line c in Fig. 4) here. I'm going to set my, "That way, I'll never..," (draws line a in Fig. 4)—the problem is if I set my criterion, so I exclude all possible noise, I'm going to miss (indicates the area to the right of the new dividing line) a lot of valuable signal. The other issue that comes up (erases line a in Fig. 4). So where do you set the criteria? Well, I mean, there isn't an algorithm for that because, part of the problem is, those different kinds of errors are differentially relevant to you depending on the context.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Let's go back to the gazelle. You have two gazelles: you have Bill the happy gazelle. And what Bill wants to do is, basically, wants to avoid leopards, right? So Bill says, "Well, I'm going to set my criterion very high (draws line c in Fig. 4), because that way, most of the time I'm going to treat the noise as a leopard in the bush. And that way my chances of missing a leopard are very small." Now the problem with Bill is he's kind of, you know, he runs away a lot. Every wind, he runs away and all the other gazelles laugh at Bill, "Look at Bill, he's running around again." And if Bill does this too much, of course, it's exhausting right?

Now in contrast to Bill the gazelle, there is, you know (erases line c in Fig. 4), let's call it Tom. And Tom is the, you know, the really epistemically-oriented gazelle. Tom will only act on the basis of what Tom truly believes. And so Tom is going to be very skeptical and set their criteria and very low. And Tom says, "I'm only going to believe (draws line a in Fig. 4) what I am really confident in and certain of and that way..." you know, this is what's going to happen. So what happens for Tom is all the instances where the wind is blowing and Bill runs away. Tom laughs at Bill, "Haha. Silly Bill." The problem is Tom is missing signal by setting his criterion so low. And one of these times there's a noise in the bush. Bill runs, Tom begins to laugh and as he's mid laugh, there is a leopard on his back, sinking its jaws in a death grip on his neck. Because you see, in this context, not in all contexts, not in all contexts, but in this context, missing signal is much worse than mistaking noise for signal.

See, there's two kinds of errors. I can miss signal (Fig. 5) (writes miss-signal). I can mistake noise for signal (writes mistake noise for signal). When I do this (indicates Mistake noise for signal) that's Bill; everybody laughs at me, that's a cost and I'm using a lot of energy. But if I miss (indicates miss-signal), if I missed the leopard, I'm dead and that's much, much worse. So that's why most gazelles are like Bill rather than like Tom, they set the criterion (erases line a in Fig. 4) way over here (draws line c in Fig. 4), they're willing to make a lot of mistakes so that they do not make very many misses. Now there's other situations where it will be reversed, where a mistake is much more costly to you than a miss.

Fig. 5

And so what you need (erases line c in Fig. 4) what you need is you need to be flexibly setting your criterion in a way that is deeply, contextually sensitive, deeply situationally aware. This is again why perspectival knowing is so crucial perspectival knowing is your situational awareness and your situational awareness should be your primary guide to: What is the context? And how do I set the criterion in this context? In fact, there's a neuroscientist—cognitive scientist, Lau (writes Lau) who argues that one of the functions of consciousness is exactly to set the criterion for perception. So what you're paying attention to is how you're situationally aware and. So how you're paying attention, how you're situationally aware, how you're setting the criterion is actually the job of consciousness. Now as you may have realized—myself and Richard Wu and Anderson Todd argued—this again is another argument that one of the main functions of consciousness is to do relevance realization within perspectival knowing yet another converging argument.

Now, the point about this is two things and both of them have to be remembered. What does this have to do with credo? Well, I would argue that what credo is, is criteria—credo is setting the criterion (draws line b in Fig. 4) on religio (writes Religio beside the bell curve). What it's trying to do is determine what behaviors, what things are putting me really into contact with religio. And then what is malfunctional? What is mad, et cetera? Now the issue is we have to set the criterion. That's inescapable. And one way to do this is to do it in an absolutist way. One way to do this is to say there is a final way, a final place, an absolute place to set the criterion. I can think. I think you can see from the argument given here, why that is a perilous thing to do.

You can see again, why the open-endedness of relevance realization undermines these—the attempt to absolutely set the criterion. So you have to set the criterion, but it is dangerous to set the criterion in an absolute fashion. So if we can acknowledge this: we can acknowledge that we will set the criterion with our mythos, but, and that's one half of credo, but we should not ever try to set the criterion in an absolute or final manner, which is what happens in credal dominance, because that is ultimately to misunderstand the functionality of setting the criterion. The point is not to set the criterion conclusively. The point is to continually reset the criterion optimally. Again, open-ended relevance realization rather than a final solution. So a way of thinking about that is the religion that's not a religion would always, always have credo in the service of religio.

Now I'm sure that there are many religious people would say, well, that is, that is what we do in practice. And, you know, we have our creeds, but they're constantly being historically interpreted. And I think that's sort of right in practice but there's often been a lot of conflict between, uh, de facto and de jure in the history of the religious discussions around orthodoxy and creed, et cetera. And I point to you again to the work of Arthur Versluis and his work on the way in which the West history of pursuing and persecuting heretics, people who do not set the criteron as we do has actually helped to foreshadow and train the West for totalitarian regimes and totalitarian ideologies. So I point you again to his historical argument for how that came about. So for that reason, we should always be thinking of making credo clearly and correctly, comprehensively, always in the service of religio, that would be helped as you can, I think see, by being linked to a notion of sacredness as being grounded in an inexhaustible, open-ended optimization rather than in some absolute state of perfection.

Mythos beholden to three levels

Next, I think that the religion that's not a religion should, when it's crafting its mythos and understanding that credo is always in the service of religio, it should always understand the mythos as being beholden to sort of the three levels that we've been talking about here.

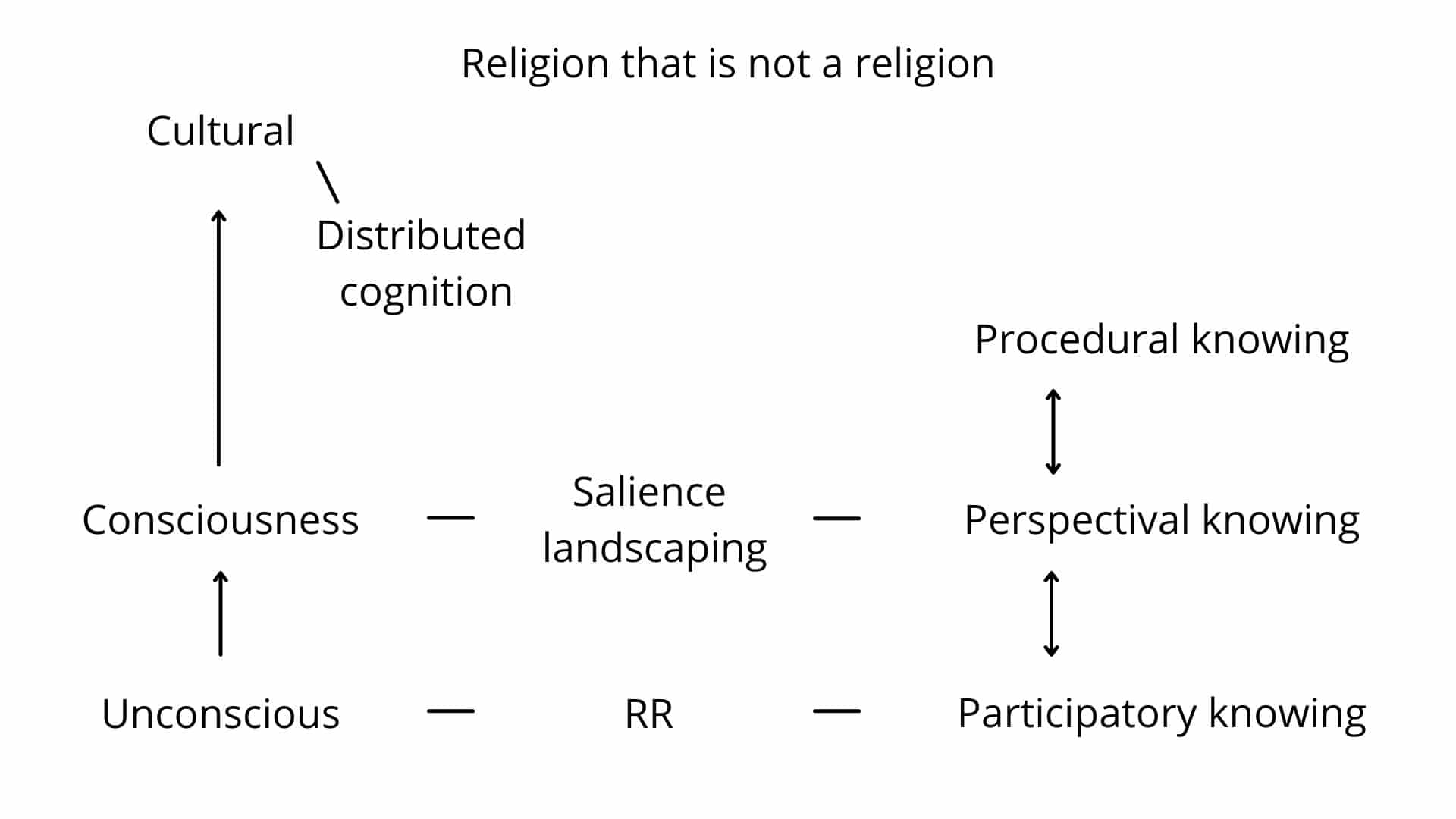

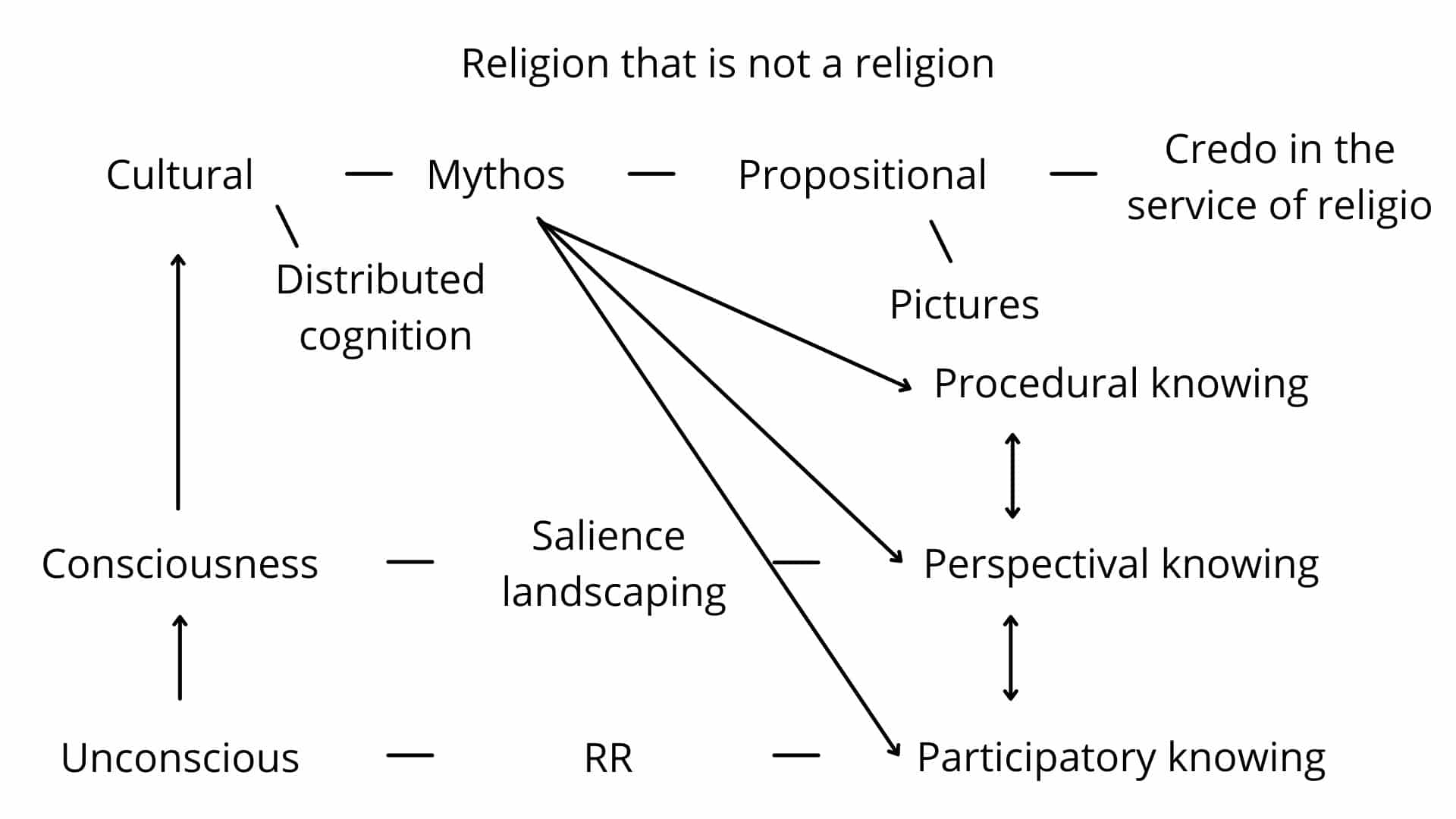

So you have the unconscious level (Fig. 6a) (writes Unconscious). This is the level at which relevance realization (writes RR beside Unconscious) is taking place. Most of the relevance realization that's going on for me, I do not have introspective access to in any way. And this of course is the grounding of my participatory knowing (writes Participatory knowing beside RR) of course, you can become conscious of your participation, but that's not what I'm saying here. I'm saying that the processes by which—from which I emerge as an autobiographical ego and the world emerges as an unfolding arena are ultimately below the level of consciousness and that's where the participatory knowing is happening.

Fig. 6a

Fig. 6a

And then of course there is the level of consciousness (writes Consciousness above Unconscious) and this is the level of salience landscaping (writes Salience landscaping beside Consciousness). And of course, this is the level of perspectival knowing (writes Perspectival knowing). The perspectival knowing is grounded in (draws an arrow from Perspectival to Participatory) the participatory. And the perspectival knowing with the situational awareness that I've just talked about, of course, makes possible the procedural knowing (writes Procedural above Perspectival knowing with a double-headed arrow between them) these are tightly intermeshed as well (draws a double-headed arrow between Perspectival knowing and Participatory knowing). This is where I am consciously directing my interactions in order to appropriate affordances given to me at this level (indicates Participatory knowing). And I'm appropriating those affordances by cultivating skills so that my coping turns into skillful interaction. My coping-caring becomes a skillful action and apt sensibility.

And then of course, this passes into the cultural level (writes Cultural). This is the level of distributed cognition (writes Distributed cognition). And this is the level at which we are trying to communicate.

So this is the level (indicates RR) at which connections are being made. This is the level (indicates Salience landscaping) at which connections are being sensed and internalized. And then this is the level (indicates distributed cognition) at which connections are being shared. And so, what we have here, of course, is the whole machinery of mythos (Fig. 6b) (writes Mythos beside Cultural). And, of course, the machinery of science (writes Science below Mythos) and other things such as that, but I'm going to—although that's at the cultural level, I'm taking it out (erases science) because what I want to concentrate on here is addressing this (indicates Religion that is not a religion). So this will pick up on our propositional knowing (writes Propositional knowing beside Mythos), but, of course, the mythos also points down towards (draws an arrow from Mythos to Procedural knowing, another arrow from Mythos to Perspectival knowing, and another arrow towards Participatory knowing) all of these, because here we have credoin the service of religio (writes Credo in the service of religio beside Propositional).

Fig. 6b

Fig. 6b

Any mythos is going to understand itself this way (indicates Propositional - credo in the service of religio). If I put it horizontally as always in the service of religio, which means it is always going to also be directed, if you'll allow me, downwards to the procedural knowing the perspectival knowing and the participatory knowing. So it should be a mythos that is explicitly committed to both of those (Propositional - Credo) in an integrated fashion. That the credo, the paradigmatic propositions, the paradigmatic pictures (writes Pictures under Propositional) are always in the service of religio and that the mythos therefore is directed towards accessing, activating, accentuating, appreciating the procedural knowing, the perspectival knowing, the participatory knowing.

Ecology of Psychotechnologies

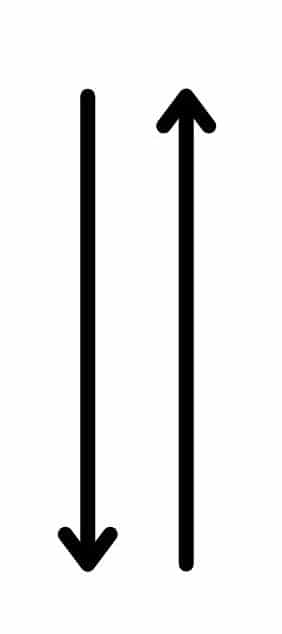

So it should be, given the argument—it's very tentative here—what it should be doing is once you you've got this programmatic framework in mind that what it should be doing is (erases the board) cultivating an ecology of psychotechnologies (writes Ecology of psychotechnologies). An ecology that is designed to be both top-down. It reaches from the propositional down (Fig 7) (draws a downward arrow) to the participatory, but also is open to (draws an upward arrow beside the downward arrow) and allows bottom-up emergence from the participatory up through the perspectival, through the procedural, and into the propositional.

Fig. 7

So I've tried to indicate to you what that ecology should look like. You should be setting up psychotechnologies, sets of practices and cognitive styles that have complimentary relationships to each other, that have sets of corresponding checks and balances, strengths, and weaknesses. So that you have a dynamical system that is reliably complexifying in a reliably self-correcting manner, which means we need to do something very important.

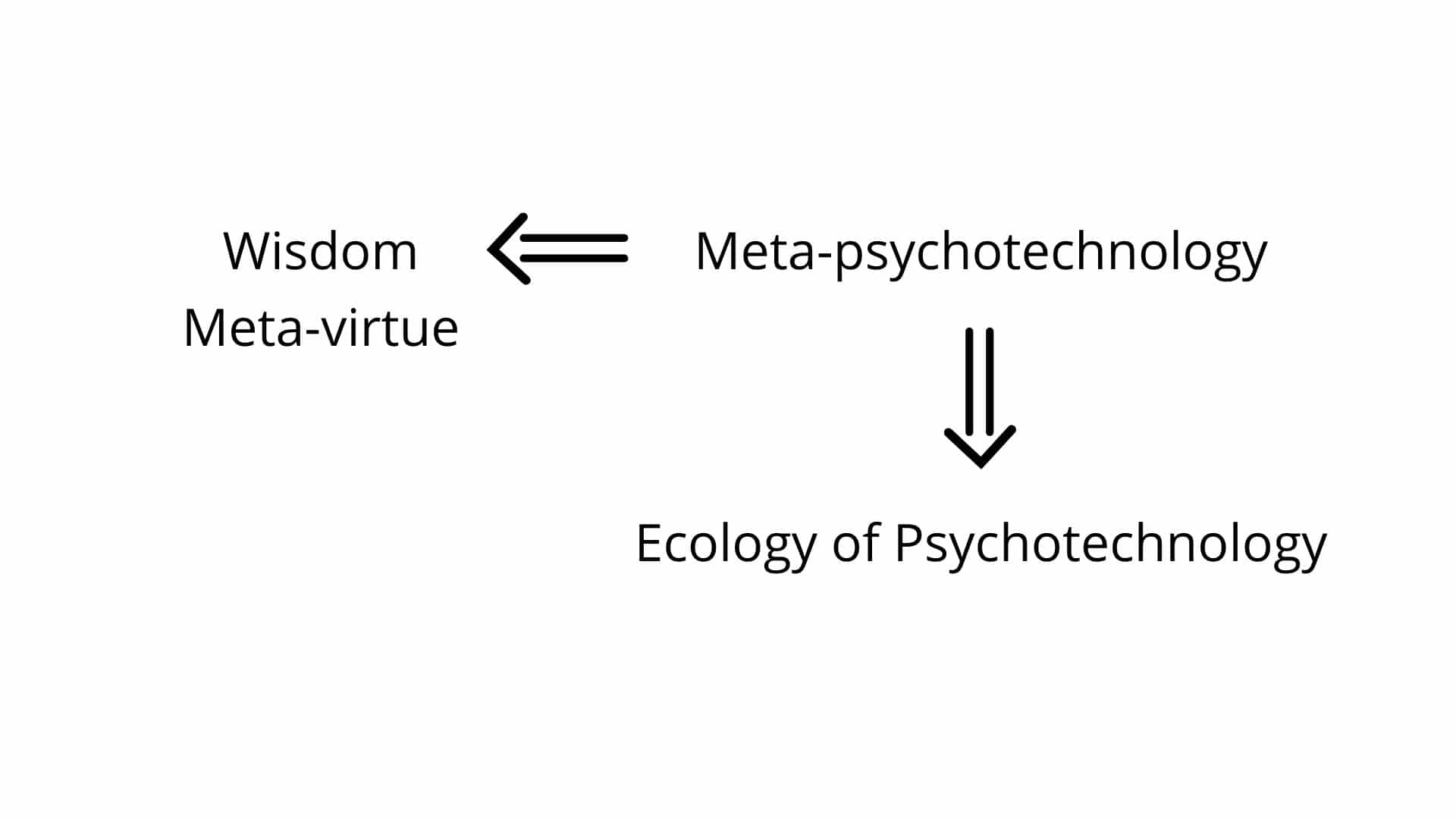

And this is an idea that emerged in a discussion with Jordan Hall (draws an upward arrow from Ecology of psychotechnologies) and he put it this wa— I think, which is a very interesting way of putting it— we need a meta-psychotechnology (Fig. 8) (writes Meta-psychotechnology above Ecology of psychotechnologies) that is designed to give us—move us (draws an arrow from Meta-psychotechnology to Ecology of psychotechnologies) out of the intuitive construction of psychotechnologies into the more explicit. So two points here: the more explicit creation of psychotechnologies (indicates Ecology of psychotechnologies) and explicitly the task of trying to cultivate an ecology of more explicitly engineered psychotechnologies.

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

So this would be the meta-psychotechnology (indicates Meta-psychotechnology). So this religion that is not a religion should give people ways of cultivating this meta-psychotechnology as a way of crafting the ecology of practices for addressing the perennial problems in a way that is always consonant with and coherent with worldview attunement.

I think that there are deep connections between the capacity for collectively creating the meta-psy—and you have to do this collectively (indicates Meta-psychotechnology), because that's how psychotechnologies are created (Text overlay appears: John will explore the nature of this meta-psychotechnology in a forthcoming series). The capacity for creating this (indicates psychotechnology) collectively (draws an arrow from Meta-psychotechnology) and the individual virtue (writes Wisdom beside Meta-psychotechnology), meta-virtue, because that's what it is: the meta-virtue of wisdom (writes meta-virtue below Wisdom). There's deep connections for that. The more that people are individually cultivating—cause wisdom is basically a way of cultivating and coordinating the individual virtues, we'll come back to that. So you need individual wisdom (indicates Wisdom - Meta-virtue), the meta-virtue, in order to collectively (indicates meta-psychotechnology) pursue the creation and the ongoing cultivation of the meta-psychotechnology (taps Ecology of psychotechnologies) that will allow us to engineer individual psychotechnologies and to cultivate a ecology of psychotech that reaches comprehensively down to our participatory knowing (indicates the downward arrow) and affords comprehensively the emergence up (indicates the upward arrow) from our participatory knowing.

So I think those are some very general structural features. Some things we might be wanting to do at a more organizational level is, and this is extremely tentative—extremely. So what might it be to create that open-ended credo?

A Credo Analogous to Wiki

Well, we have something like that already because of the emergence of the cyber technologies that are being increasingly integrated with the psychotechnologies. And I'm using this just as an analogy, but we have something like Wikipedia and what's interesting about the Wikipedia is the way it's generated, the way it's maintained, the way it's revised. It's done in this collective cooperative fashion. And it has both quite reliable stability, but also a quite reliable evolution. And what's interesting is I've recently exp—with the worker—with the work of co—constituted as any of... Created something like this for one of my courses. And what we did there in one of the courses at the university has got former students to basically create a Wiki of some of the main ideas, main themes, main arguments in the course. And what happens is people, of course, get much more involved in a participatory fashion with the generation of sort of the credo for the course. And what they also do is they create something like the Wikipedia that gives people much more interactional and evolving content to work with. So you get sort of this presentation of what's paradigmatic and prototypical for the course, but in this collective dynamic and ongoing fashion.

So perhaps we could think about creating a credo analogous to that, where we create something like a Wiki—a credo Wiki, for example, by which groups of people that are interested in creating ecologies of practices and psychotechnologies can communicate with each other for how to adaptively set the criterion and how to constantly re-engineer the creation of the meta-psychotechnology that will help to guarantee— maybe that's too strong, a word—help to promote, reliably promote both the bottom-up and top-down functionality of this ecology of psychotechnology. Maybe that could be set in conjunction with a co-op structure of these various communities where they are co-opting together to create a shared curriculum, a shared credo in this Wiki manner and which they are also trying to afford a kind of synoptic integration, a shared vocabulary, not imposed as an ideology, but to allow for transformative and bridging insights and discourse between the various groups so that they might be able to afford each other's development and enhancement.

Now, as I've said, all of that is not—this—I am not presenting a utopic vision. That's not what's going on. What's going on is: people are already doing this. They are already trying to create these ecologies of practices. They're trying to create ways of talking to each other, setting the criterion and they're making use of social media. They're making use of the internet. They're making use of cooperative dynamic forms of social organization. I think all of those could be appropriated and a way to help bring about this religion that's not a religion. And what I've tried to do is offer some suggestions on things to keep in mind and at least some potential methods for helping to bring this about whether or not this functions, whether or not any of this takes root. Again, it's not even up to me, I'm not some sort of linchpin or pivotal figure. I'm just trying—this sounds so insufficient. I'm just trying to help. I'm really just trying to help. I want to give people some way of how to go about starting to make this work more and more powerfully and perspicaciously.

All right. So I have tried to show how in three interrelated ways we can respond to the meaning crisis. I've tried to show that we can—there are sets of practices that we can cultivate as an ecology for addressing the perennial problems. We can set those perennial problems into a legitimating worldview via the theoretical, scientific machinery given to us by third generation cognitive science, 4E cognitive science. And that all of that can be set practically within the project of trying to bring about the religion that is not a religion in terms of, like I said, some suggestions about some structural features of what we're looking for and some organizational features of how to try and initiate that and get that going. This is ultimately going to come back to the dialogue that I'm going to set up between what I've argued for here and some of the other profits of this religion beyond a religion, that's not a religion like, Tillich, Jung —I would argue, also Corbin and perhaps aspects of Barfield, and the godfather of all of that, of course, are people like, Heidegger.

So that's going to be something we're going to come back to, but we need to do something else now that I've constantly been putting aside, because it also is going to be involved in the process that I have been proposing to you, and we've said it throughout, which is the cultivation of wisdom. And as we've seen the cultivation of wisdom as a meta-virtue is deeply resonant with the communitas's cultivation of the meta-psychology that is needed for the ecology of psychotechnology. And, of course, wisdom is also needed for the project of enlightenment—I've already mentioned. And finally, wisdom has always been associated since the Axial Revolution with satisfying those deep connectedness, the connectedness to oneself, the connectedness to the world, the connectedness to others that makes for a meaningful life.

Cognitive Science of Wisdom

So I want to start talking now about the cognitive science of wisdom. And I want to—and again, this is a very exciting and hot area in cognitive sci. There's lots going on about this right now and it's becoming very, very pervasive. And the discussion of wisdom in the culture at large is coming to the fore again. So I can't, I mean, I would like to have a series at some point that's just on wisdom. I can't do that right now. What I want to do is try and give again, sort of a very quick overview of sort of the key players—if you'll allow serious players in the cognitive science of wisdom business—and what we can glean from that. And how we can integrate it into the model and picture we've been building here.

So this really took off in the 1990s with an anthology by Robert Sternberg, the psychologist. Robert Sternberg has done a tremendous amount of work to bring back the notion of wisdom within psychology, within cognitive science in general, and even within pedagogy and the understanding of education. And that anthology really started to bring out some of the initial work that was being done, the seminal work; and also promote a lot of work that has expanded since on this.

I want to talk about work that was happening at around the same time as this shortly thereafter. So the Sternberg—the first Sternberg anthology on wisdom (there's been another one since: the Wisdom Handbook) was in 1990. And then, what I consider a really important article came out in 1999 by Mckee and Barber (writes 1999 and McKee and Barber). It was important because it was basically retrospective, reflection on sort of the first decade of work on wisdom. But it was doing something more than that. So it was definitely doing that retrospective, but it was also doing something very important. Something that is so resonant with what we've been doing here together, because what they wanted to do was they wanted to try and link two things together in a very powerful convergence argument.

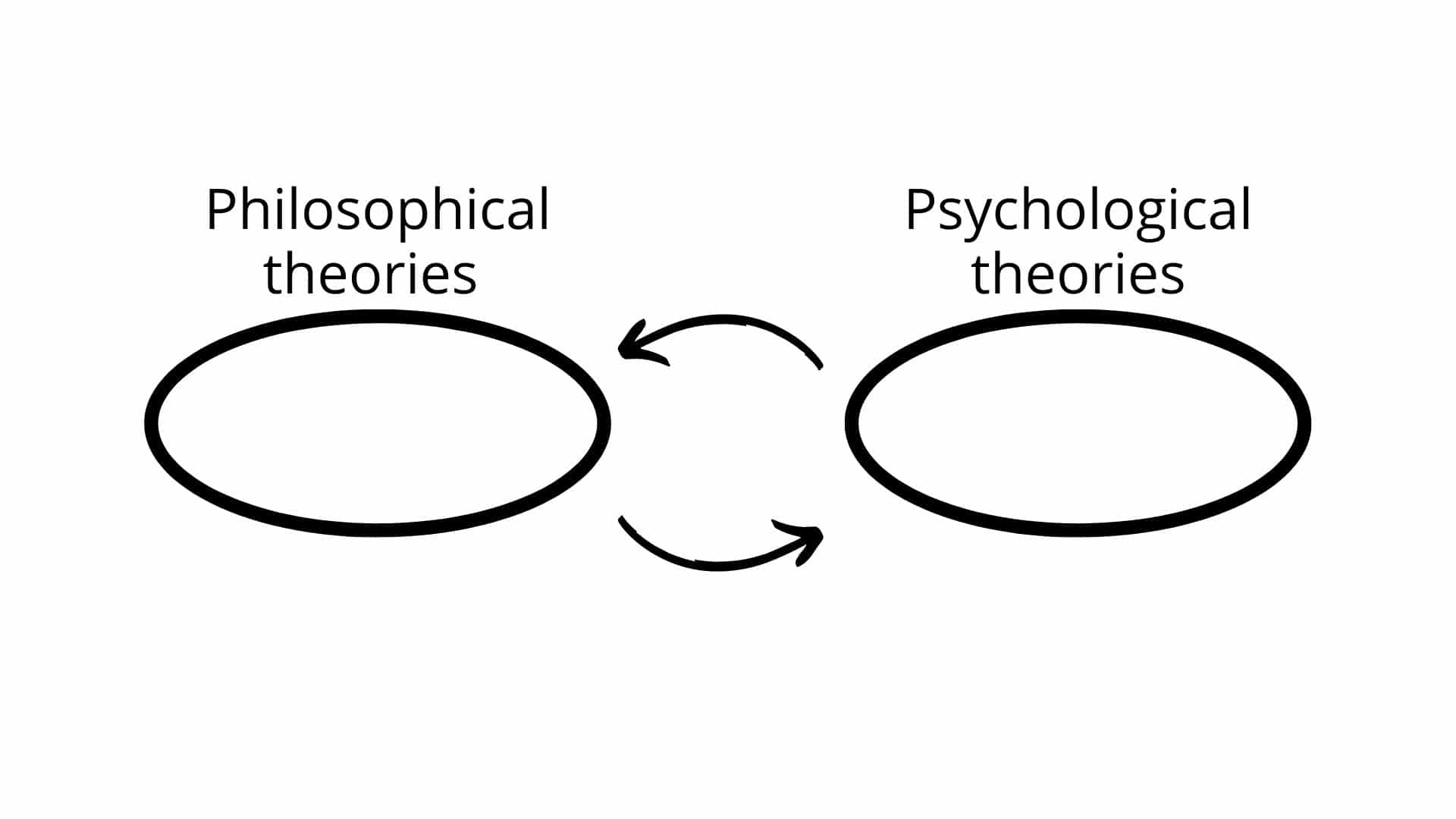

A Reflective Equilibrium

They wanted to look at all (draws an oval) of what they call the apriori theories of wisdom. Our way of understanding that and I think that it's very easy just by seeing what they looked at. They wanted to look at all the philosophical theories (Fig. 9) (writes Philosophical above the oval) and we've looked at quite a few of them. So we have an understanding of what they're talking about. We saw the Socratic theory and Aristotelian and the Stoic, and the Platonic. So you have the philosophical theories of wisdom (adds Theories to Philosophical) and, of course, that's appropriate because philosophy is the love of wisdom. But they also wanted to look at (draws another oval beside the first). And there had been about 15 years 'cause the anthology comes out in 1990. Some work had been going on in the eighties and then it starts to really take off, but you've got the psychological theories (writes Psychology theories above the second oval).

Fig. 9a

Fig. 9a

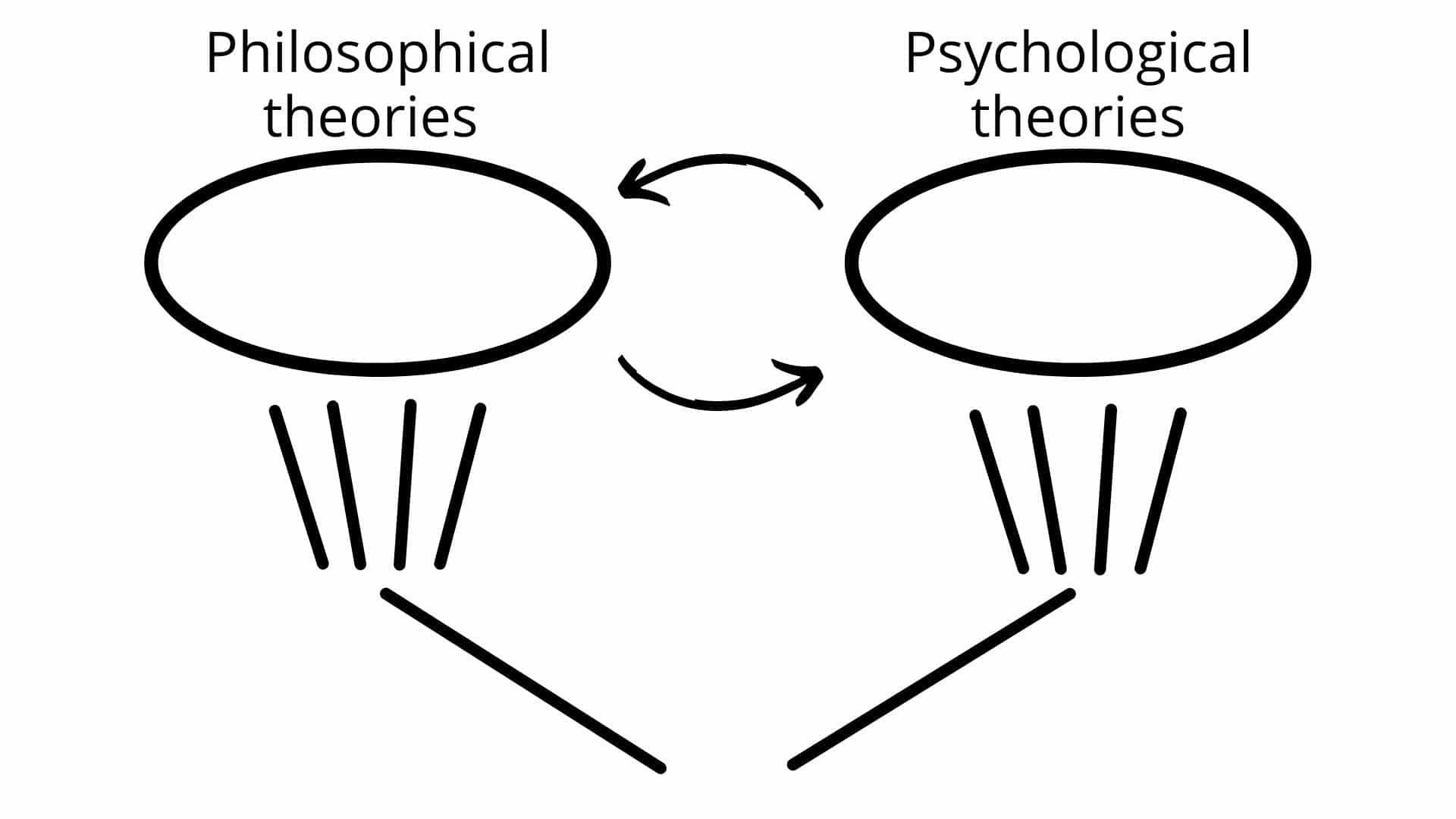

Now, these (indicates Philosophical theories) are very conceptually-driven. They're very sort of top-down. These (indicates Psychology theories), of course, are much more empirically-driven bottom-up. And what they were trying to do was they're trying to set up a, basically (draws an arrow from the first oval to the second oval), a reflective equilibrium (draws an arrow from the second oval to the first oval) between them.

They're trying to find... they're trying to find through a coordinated investigation, a convergent theme. Both from all of the philosophical work and all of the psychological work. So looking at all of the philosophical work (draws converging lines below the first oval), what does it converge on? Same thing with the psychological work (draws converging lines below the second oval) and then can we draw it altogether (Fig. 9b) (draws another set of converging lines joining the first two sets) in a reflectively coherent fashion? And they did.

Fig. 9b

Fig. 9b

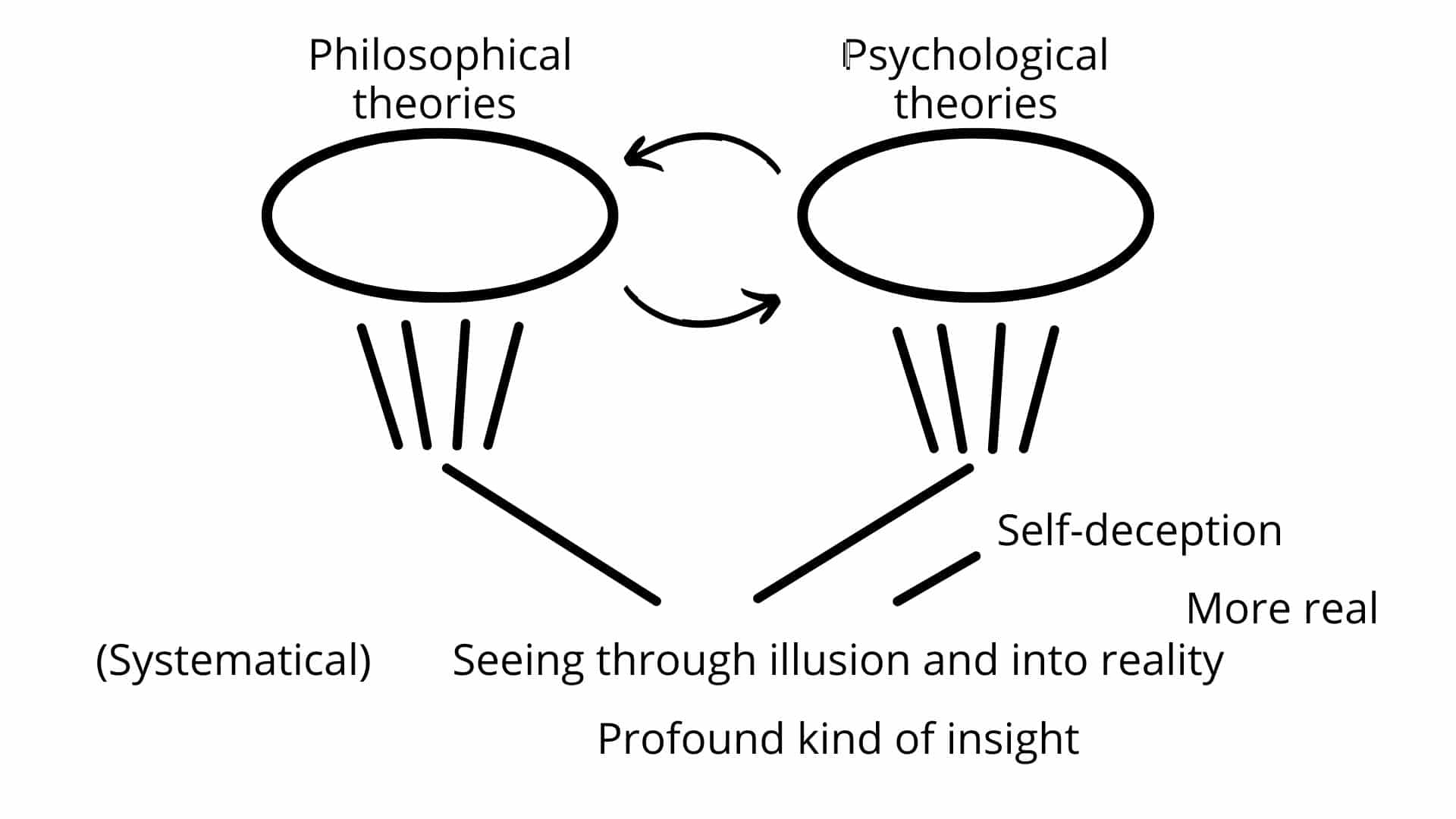

They make a very powerful argument. They go through and they make an argument that what all of these theories converge on is seeing through illusion (Fig. 9c) (writes Seeing through illusion). That the core of wisdom is the ability to see through illusion where this means, of course, much more broadly. They're not meaning primarily here visual illusion, they're meaning (writes Self-Deception above Seeing through illusion) cognitive and existential illusion that is caused by self-deception. So seeing through this (indicates Seeing through illusion). And they—and, of course, because wisdom is a systematic notion and this is something they are going to explicitly argue about.This is systematically (writes (Systematical)). So not just this illusion or this self-deception, but a systematic seeing through of self-deception. And then in something that Leo and I published in—Leo Ferraro and I published in 2013, we argued that this (indicates Seeing through illusion), of course, has a strong implication that should be filled out here. Seeing through illusion and into (writes And into reality) some sense of what's reality or, at least, what's more real (writes More real above Reality). And because you can only know if you're seeing through illusion if you come to something that you regard as being less illusory in nature. So this is directly (indicates (Systematical))—the systematic—seeing through illusion and into reality.

Fig. 9c

Fig. 9c

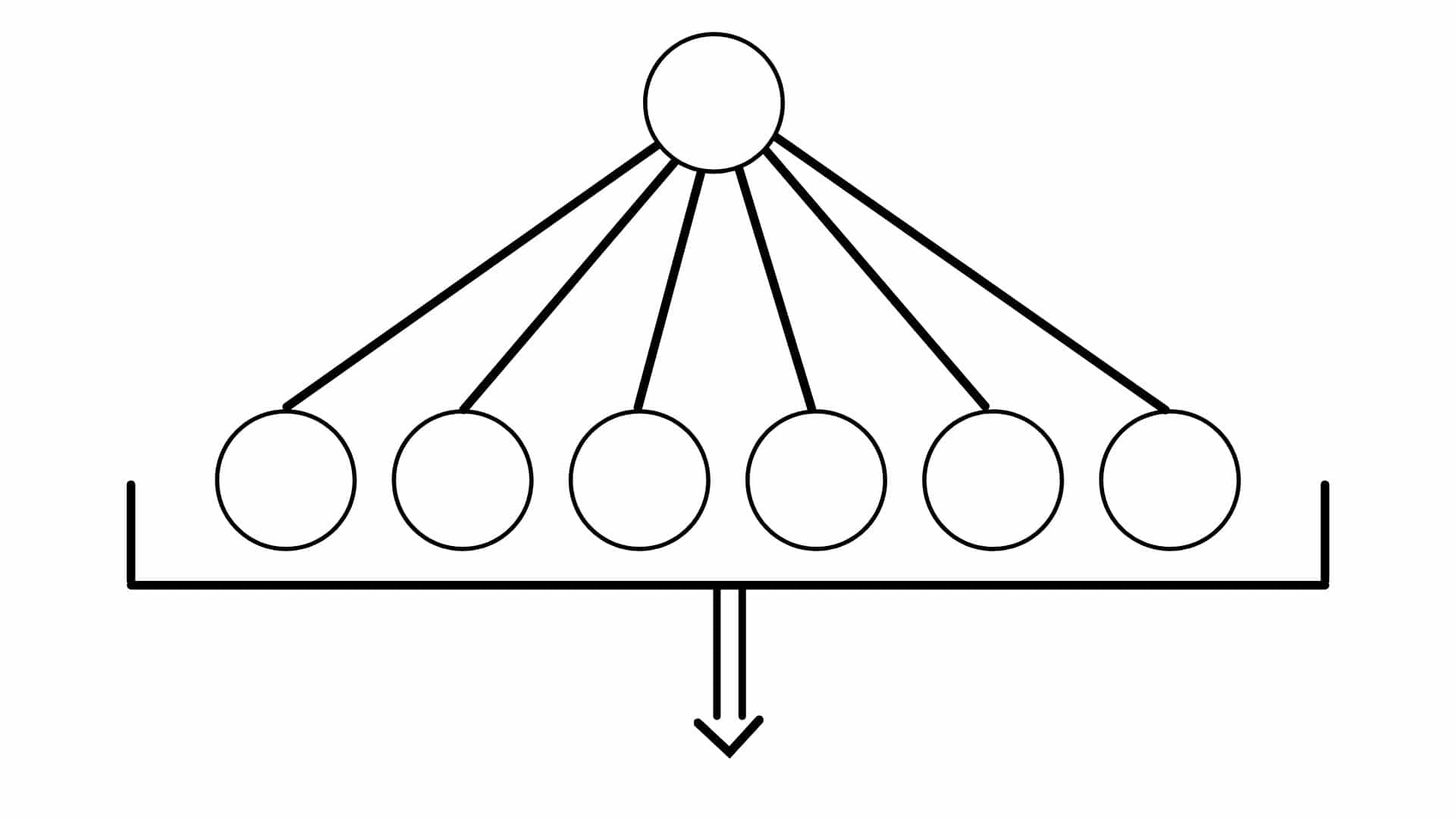

Now, notice what this is. This is a very profound, meaning both deep, and pervasive, meaning across many different instances of where you're trying to solve your problems, achieving your goal. This is a very profound kind of insight (writes Profound kind of insight below Seeing through illusion). It's a systematic insight that we talked about when we talked about higher states of consciousness. And we'll see that Mckee and Barber are using exactly this idea. It's too find across many areas (Fig. 10) (draws six circles in a line) in which you have been misframing problems (draws lines from each circle that converges on a single point above them) to see them, to realize them as systematically related, such that you can come up with an insight (draws a circle where the line converges) that intervenes not just on this problem (indicates the circle where the lines converge) but in all of these problems (indicates the different converging lines) in a systematic fashion and thereby you start to see (indicates (Systematical) systematically through illusion (indicates Seeing through illusion) and into (draws a bracket with a downward arrow below the circle with converging lines) what is more real. So this is a key idea as to what you're trying to cultivate when you cultivate wisdom.

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

And what we're going to do next time is we're going to continue to look at—we're going to follow this (indicates Fig. 9c) about putting the psychological theories and the philosophical theories into dialogue and to continue developing what is it that we're talking about when we're talking about wisdom and, relatedly, what is it we're doing when we're proposing the cultivation of wisdom?

Thank you very much for your time and attention.

- END -

Episode 39 Notes:

To keep this site running, we are an Amazon Associate where we earn from qualifying purchases

James Carse

James P. Carse was an American academic who was Professor Emeritus of history and literature of religion at New York University.

Book Mentioned: The Religious Case Against Belief - Buy Here

Roberto Mangabeira Unger

Roberto Mangabeira Unger is a Brazilian philosopher and politician.

Book Mentioned: The Religion of the Future - Buy Here

Alain de Botton

Alain de Botton, FRSL is a Swiss-born British philosopher and author.

Book Mentioned: Religion for Atheists - Buy Here

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins FRS FRSL is a British ethologist, evolutionary biologist, atheist thinker, and author.

Nones

Irreligion, or nonreligion, is the absence or rejection of religion, or indifference to it. According to the Pew Research Center's 2012 global study of 230 countries and territories, 16% of the world's population is not affiliated with any religion. The population of religiously unidentifying people, sometimes referred to as "nones", grew significantly in recent years, though its future growth is uncertain.

Tomas Björkman

Tomas Björkman (born March 3, 1958 in Borås, Sweden) is a Swedish financier, social entrepreneur and author.

Nicene Creed

The Nicene Creed is a Christian statement of belief widely used in liturgy. It is the defining creed of Nicene Christianity.

Apostolic Creed

The Apostles' Creed, sometimes titled the Apostolic Creed or the Symbol of the Apostles is a Christian creed or "symbol of faith".

Credo

In Christian liturgy, the credo is the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed (or less often, the Apostles' Creed or the Athanasian Creed) in the Mass, either as spoken text, or sung as Gregorian chant or other musical settings of the Mass.

Timothy Lillicrap

Timothy P. Lillicrap is a Canadian neuroscientist and AI researcher, adjunct professor at University College London, and staff research scientist at Google DeepMind, where he has been involved in the AlphaGo and AlphaZero projects mastering the games of Go, Chess and Shogi. His research focuses on machine learning and statistics for optimal control and decision making, as well as using these mathematical frameworks to understand how the brain learns.

Blake Richards

Blake Richards is an Assistant Professor in the Montreal Neurological Institute and the School of Computer Science at McGill University and a Core Faculty Member at the Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute.

Article Mentioned: Relevance Realization and the Emerging Framework in Cognitive Science

Arthur Versluis

Arthur Versluis is a professor and Department Chair of Religious Studies in the College of Arts & Letters at Michigan State University.

Book Mentioned: The New Inquisitions - Buy Here

Robert J Sternberg

Robert J. Sternberg (born December 8, 1949) is an American psychologist and psychometrician. He is Professor of Human Development at Cornell University.

Book Mentioned:

Wisdom: It’s nature, origins and development - Buy Here

A Handbook of Wisdom: Psychological Perspectives - Buy Here

The Cambridge Handbook of Wisdom - Buy Here

Book Mentioned: the Scientific Study of Personal Wisdom - Buy Here

Article Mentioned: On Defining Wisdom

Other helpful resources about this episode:

Notes on Bevry

Additional Notes on Bevry